Accelerating Change through Government-CSO Collaboration: Field Experiences from Bastar

Government officials (District Collector, CEO- Zila Panchayat and CEO- Janpad Panchayat) discussing the lift irrigation plan with VO members in Dhodrepal village, Darbha block, Bastar

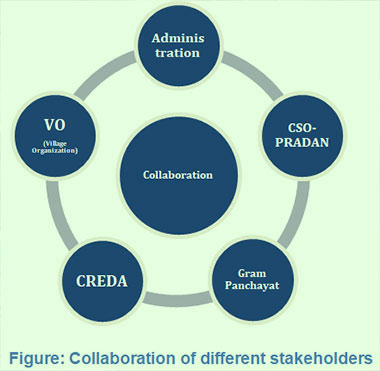

Combining the resources of the government, the expertise of the CSO and implementation by the community is the way forward, with each contributing its strength and providing what the others cannot while recognising the value of interdependence

Introduction

T here is no gainsaying the merits of a government–civil society organisation (CSO) partnership or collaboration for better outcomes in developmental programmes. The usual rhetoric about how to maximize the impact of developmental projects such as the ones on health, education or livelihoods are replete with ideas favouring strategic collaboration between the government and CSOs, both of which bring to the table their own strengths and capacities. The government brings with it power, policies, programmes and finances, and the CSOs their strong foothold at the grass roots and expertise in certain domains. One complements the other as they move toward a common goal, for example, the reduction of rural poverty. Taking cognizance of the potential roles a CSO can play, governments have strategically opened up the collaborative space, in the recent past and through favourable policies, with CSOs to implement some key rural development programmes such as NRLM and MGNREGA.

Whereas rhetoric abounds, impactful stories of success through sustained, functional, collaborative efforts at the ground are rare. Therefore, there is great virtue in sharing success stories, which we attempt to do in this article.

The story pertains to one of the most remote geographies of the country—Bastar—in the state of Chhattisgarh, a poverty-stricken area notorious for prolonged unrest due to left-wing extremism by outlawed Maoist outfits. There have been some rich experiences and emerging evidence of change over the last 3–4 years through the joint action taken by the district and block administrations of Bastar district and the CSO—PRADAN. PRADAN has been a longstanding partner of the state government in some of its flagship rural development programmes such as NRLM and MGNERGA across many districts in the state. Such endeavours are usually conceived of and formalized at the central or state units (of both the CSO and the government), with the intention of bringing efficacy and effectiveness in programme implementation. It paves the way for joint engagement at the local levels, that is, the district or the block level teams. This may not, however, always guarantee an effective and sustained collaboration unless further efforts are made, at the implementation level, to strengthen partnerships. If the intention and the purpose are coherent, and serious efforts are made by both the government and, mainly, the CSO, trust accumulates, which eases the course of collaborative actions.

The Region and the Actors: A Brief Description

Darbha is the southernmost administrative block of Bastar, a district registered as a NITI Aayog aspirational district. It is bordered by Sukma and Dantewada districts to its south and south-west, respectively, and by three other Bastar district blocks in the remaining directions. Tribals (such as Maria Gonds, Dhurwas and a few others groups) claim the largest share (83 per cent) of its population for whom conventional agriculture and wages make the two most important livelihoods. More than 60 per cent of its area is clad in dense tropical forests and the landscape comprises both plateau areas with moderate slopes and highly undulating areas with steep slopes. Its scenic beauty and the presence of a national forest (Kanger Valley National Forest), waterfalls and caves make it a tourism hotspot as well. Despite these, the block is also known for its widespread poverty, low levels of education (especially among women) and undernutrition, which makes it imperative for the government to pay special attention and intensify development action.

Like anywhere else, the district and block administration is the largest stakeholder in the developmental works in Bastar. Social security, livelihoods, nutritional and other developmental tasks are the major deliverables of the administration. Besides the regular central and state government-sponsored programmes, owing to its status of being a mining affected and an aspirational district, it is additionally resourced under provisions such as district mineral foundation, special central assistance, and other tribal welfare schemes.

PRADAN is counted as an important national CSO in the areas of rural livelihood promotion and has vast experience of working mostly with Schedule Tribe (ST) populations in the far-flung areas of central and eastern Indian states. In Bastar, it has been operational since 2009 covering Darbha block and parts of an adjoining block—Tokapal. With the purpose of making rural lives better, a PRADAN direct action team employs its core strategy of first collectivizing women into Self Help Groups (SHGs) and its higher tiers such as village organizations (VOs) and Federations and then initiating locally suitable livelihood activities (mostly agri-based). Developing and nurturing community resource persons and entrepreneurs, mobilizing livelihood finances in cash and kind (both capital investment and working capital) from government and financial institutions, conducting market studies to inform production choices, setting up functional linkages with the market, etc., form other key strategies that PRADAN employs in pursuit of the larger goal of equitable growth of the local economy, thereby, reducing poverty. This coherence of vision makes PRADAN qualified to be a key stakeholder with the government, which complements its work as financier and co-implementer.

Why Collaboration? Why Bastar?

T he government is certainly the key driver of ‘development’. It has the wherewithal and potential to usher in large-scale changes in sectors such as health, education, sanitation, job-creation, etc. In the last few decades, the government’s efforts have primarily been responsible for propelling the country into a trajectory of positive change in many areas of development. However, the results in agriculture-based livelihoods or job creation has not been commensurate with the growth in other sectors. It has actually fallen in the last few decades. The situation is even more dire in tribal hinterlands, causing mass seasonal exodus of rural people (especially young adult males) in search of jobs elsewhere. Whereas migration for jobs in city-centric sectors such as construction, manufacturing and services is a natural corollary of the relatively stagnant rural agriculture sector, there is a limit to it and there is no alternative but revival of the agriculture sector to employ a sizable proportion of the population. As it usually turns out, agriculture-based livelihoods promotion programmes are particularly fraught with various challenges whereby components such as adoption of new technology or methods, enhancing productivity, bringing efficiency and quality, ensuring community participation throughout the process, etc., become indispensable. This calls for committed, long-term engagement not just in the techno-managerial aspects but also equally in socio-economic and political processes within the community such as organizing the community, leadership development, entrepreneurship development and market linkages. The challenges are compounded in tribal settings such as in Bastar, where people are culturally different, illiterate (especially women) and speak different tribal vernaculars.

The government while being well-endowed with financial and human resources with its well-intentioned programmes, is sometimes constrained on the above counts. For instance, given the systemic challenges and circumstances such as timeline pressures, multitude of workload and sometimes the village politics of elites it's often painstaking for government frontline employees to filter out the right beneficiaries for many subsidy oriented programmes (e.g., in-kind individual subsidies by, say, the Agriculture department or CREDA). Even when a good infrastructure, such as a dam, a dug-well, a solar pump or a nursery shed-net is created without technical flaws, turning them functional, that too for the benefit of the right people, is an uphill task. This is partly because all of these require some serious and skillful engagement around community mobilization, capacity building, robust extension services, entrepreneurship development etc, which we already discussed above. Here comes the role of credible CSOs with substantial grassroots experience. They can complement by filling these undesirable gaps in the process of changemaking.

Joint Commitment: Building the Relationship

T he coming together of PRADAN and the district administration of Bastar was underpinned by a deep commitment by both, to usher in significant changes in tribal lives and livelihoods. PRADAN, with its presence in the district for over a decade, was known to government departments. PRADAN has been an official partner in the government's NRLM programme in Darbha. Earlier, it had partnered with the government to facilitate the better implementation of MGNREGA in the block through the erstwhile Cluster Facilitation Team (CFT) project as well. These arrangements were important; and more action was needed to position itself as a significant partner of the local administration. It took the PRADAN team some strenuous and persistent efforts such has holding regular dialogue and communication, sometimes negotiations, creating or seizing opportunities to present its work and so forth. Joint field trips offered good breakthroughs. It proactively presented and showcased its agri-based livelihood works to key people, mainly, the district collector, Zila Panchayat CEO and the Janpad Panchayat CEO, through joint field visits and community meetings The administration now recognizes PRADAN as a key resource and partner in its endeavours in the promotion of agri-based livelihoods.

Night stay in Madarkonta village, Darbha block. District Collector Shri Rajat Bansal and Deputy Collector Shri Kaushal Tendulkar having traditional food with a tribal family.

Fruits of Collaboration

T he collaborative relationship between PRADAN and the administration started off a series of agri-based livelihood interventions. It has brought ever more rigour and intensity to these. PRADAN did the planning with the Community based organisations such as the SHGs, VOs and Federations, and the administration approved the plans for implementation. Procedural requirements such as the necessary paperwork, estimate-making, etc., were completed jointly by PRADAN and the line departments under the active support and supervision of the Zila and/or the Janpad Panchayat CEO.

Interventions such as high-value vegetable farming (mainly during kharif) underwent significant changes in terms of coverage, yield and production once the government supported the process with some critical inputs such as providing seedlings and plastic mulch, transporting vehicles for produce marketing and so on. Despite being affected by COVID-19, last kharif (2020) saw a record sale of 415 MT of vegetables in various small and large markets. The success of the kharif vegetables created a good amount of groundswell within the community to demand for perennial sources of irrigation. Thus, came the big initiative of installing solar-powered micro lift irrigations (MLI) planned by villagers under PRADAN’s guidance at suitable sites across Darbha. The MLI initiative proved to be a significant milestone in the journey of PRADAN-government collaboration. Involved in this initiative were multiple agencies, namely, the district administration, Chhattisgarh Renewable Energy Development Agency (CREDA), PRADAN and the women’s collectives. The total project cost of 101.42 lakhs was mobilized through convergence of Special Central Assistance (SCA), MGNREGA, NRLM and the community’s share in installing 40 units of MLIs across different villages. It would ensure 980 farmers enhance their cropping intensity two to threefold, through assured irrigation of close to 1,000 acres of homestead land.

The assured irrigation opened up opportunities for development of integrated agri-horticulture cropping systems, which inspired the planning of fruit crops (mango orchards) in the command areas. These plans were subsequently approved of and financed under the district mineral funds and other sources. Together, we are developing the badi (homestead) model as a key component in achieving the ambition of doubling farmers’ income. Convergence with the animal husbandry department and MGNREGS has given much impetus in establishing the livestock initiative in Darbha block. The department has extended support in establishing the cold chain system and providing training to the cadres. MGNREGS funds are extensively used for construction of livestock sheds and NADEP tanks. Afforestation plantations (Arjuna trees—food plants for the tasar silkworm) in 300 acres of upland with the objective of tasar sericulture promotion is another example of our collaborative effort. We are now joining hands with government to implement successfully the state government’s flagship programme, Narua Garua Ghurua Badi (NGGB). Besides developing Badi, which is a core component of the NGGB programme, efforts are underway to develop model NGGB villages such as Dhodhrepal village in Darbha block.

In the course of time, the CBOs too were involved in such processes, with a vision to empower them politically and to turn the tables for them to be able to win the space that PRADAN is now occupying. Today many of the VOs and the Federation leaders know the key government functionaries and vice versa. Increasingly, they are coming up with their own plans and seeking PRADAN’s help to guide them through the processes of negotiations with the government.

The Deputy Director, Horticulture, at the lift irrigation site in Dhodhrepal village

Expansion of Solar-based, Micro Lift Irrigation – A Case

PRADAN pioneered the promotion of community managed MLI in the 1990s and since then has been implementing it in irrigation-poor, central and eastern Indian states.

In Darbha of Bastar, it started with a demonstration at one site. In this model, water from perennial sources is lifted to lands in the upper catchments (preferably fenced homestead lands) through solar powered pumps and underground PVC pipelines. Expanding the model to other potential sites (there are hundreds of such sites) required substantial investment, which was possible if the district administration was on board with the idea. In 2019, a project on “Homestead development through MLI” was sanctioned by district administration for 40 sites in Darbha. Today, of those 40 sites, 30 are functional (the rest are work in progress). For the first-time, a year later, farmers across many villages grew winter crops. This model is being greatly appreciation by the different stakeholders, and many are visiting the site to learn and operationalise similar irrigation facilities in the other blocks.

In Darbha of Bastar, it started with a demonstration at one site. In this model, water from perennial sources is lifted to lands in the upper catchments (preferably fenced homestead lands) through solar powered pumps and underground PVC pipelines. Expanding the model to other potential sites (there are hundreds of such sites) required substantial investment, which was possible if the district administration was on board with the idea. In 2019, a project on “Homestead development through MLI” was sanctioned by district administration for 40 sites in Darbha. Today, of those 40 sites, 30 are functional (the rest are work in progress). For the first-time, a year later, farmers across many villages grew winter crops. This model is being greatly appreciation by the different stakeholders, and many are visiting the site to learn and operationalise similar irrigation facilities in the other blocks.

Final words

What inspired this piece of writing could well be a curious question for some. After all, talking of just one administrative block may not qualify for any great significance. And ‘collaboration’ has always been a highly debated topic because the success stories are very few; many ideological and strategic differences among those collaborating stand in the way. Frequent changes in the top leadership makes matters even worse, with the new officers being often predisposed to other priorities. It takes another couple of months or so to onboard the new officer in charge. Therefore, maintaining a good relationship with the rest of the government officials such as programme officers, becomes important.

The intention through this piece is to share bits from an enriching journey, however small, and convey the key learnings. One, that collaboration needs to be arduously built and nurtured and once the priorities are aligned, faster and effective results follow. It was not a one-time event but rather an uneven journey characterized by consistent and persevering efforts by the CSO and openness of the government leadership to collaborative action. Demonstrating ‘tangible' and 'significant’ changes in the community really does help. The difference produced by collaborative action was evident in the quality and impact of the interventions.

Acknowledgement: We are grateful to Shri Indrajeet Singh Chandrawal, IAS, CEO, Zila Panchayat, Bastar district for his encouragement and valuable inputs.