Agriculture Interventions with the Tribals in Bastar: Priorities in the Wake of the Pandemic

Turning a global crisis into an opportunity to attract and retain the youth of the villages, who had been migrating to cities in search of work so far, the PRADAN team in Bastar district is motivating villagers to look at different options such as growing vegetables in their homesteads and animal husbandry as well as creating forward market linkages as viable options to sustain themselves

Drone/Ariel view of homesteads land from Alwa village, Darbha block

Context

T he surge in COVID-19 cases in India has become the chief cause of worry. Not just because of the imminent risk of losing lives but equally, or perhaps more, because of livelihoods being lost on a massive scale. Some experts argue that the toll claimed by the latter will, in all likelihood, surpass the former, especially because of the probability that the virus may linger on for quite some time. Poor communities have been hit the hardest by this pandemic crisis because, for many of them, the remittances they received made for a good share of their annual earnings. That the unfortunate migrants would prefer to go back to their faraway work destinations again is highly unlikely, given that they bore the brunt of the unprecedented loss of jobs, of living in shelter homes under subhuman conditions, of walking long distances to reach their homes and so on.

No surprise that the story is the same in Bastar1 in Chhattisgarh. Early trends indicate that each administrative block (out of 32) will have an estimated 1,500–2,000 migrant workers returning from neighbouring Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra, which adds up to at least half-a-lakh migrants from the entire region. Fuelled by rising aspirations, especially among the youth, and the limited local job opportunities, each passing year has seen a gradual rise in the number of villagers migrating for seasonal work between December and June. We can now anticipate a post-COVID, new normal with fewer number of people wanting to migrate long distances for work. The imperative now, therefore, is to provide livelihoods locally. By far, farm-based livelihoods is the option with the most potential available in rural spaces. The challenge, however, is to invent or develop farm-based interventions that can effectively contribute to decent and dignified livelihood opportunities for these downtrodden tribal communities in a sustained way.

Rural Bastar and the Current State of Agriculture

R ural Bastar is a land of tribes, including the Maria Gonds, Murias, Halbas, and Dhurwas, who make 25% of Chhattisgarh’s total tribal population 2. Living on subsistence mainly, the survival challenges confronting these tribes today are not the same as before. Traditionally and culturally, these tribals were not agrarian communities; even now, they identify themselves more with the forests. Bastar is no exception with more than 50 per cent3 of its geography covered by forests, making its rural population highly dependent on forests for survival. However, in today’s macro context of the dominance of the market economy, having all their needs supported by only forest-based activities is far from prudent reality. In all likelihood, forests, farms and markets (in varying degrees) have contributed to a tribal family’s livelihoods and life, fulfilling the needs and the rising aspirations of its members, especially the youth. Of the three, the share of agriculture in household income is, currently, the highest.

However, the current level of returns from agriculture is precariously low. A survey conducted by PRADAN4 , a non-profit working in Bastar district for a decade now, revealed that the annual household income of the tribal households in one of Bastar district’s blocks—Darbha—is Rs 52,000 (an average of 1,240 households), wherein the share of agriculture was as low as Rs 17,700 (34 per cent). Another data from the state government’s official portal reveals that the average paddy production, the most important cereal crop, in all districts of Bastar taken together, is as low as 1.13 MT/ha 5. This rather pitiful state of tribal agriculture is by no means attractive for farmers, especially youth, to tie them to this occupation. This has to change.

Experience from Darbha Block, Bastar

Initial interventions for increased production and return

I n the above context, the example of the work of a PRADAN team in Darbha block is worth considering. In 2016, the team initiated an intensive agriculture programme with women SHG members from the tribal communities as the primary clientele. The team has been successful in popularizing the livelihood not only among the SHG women but many of the youth in that area also have started taking serious interest in agriculture.

The team has successfully demonstrated the potential of growing vegetables during the kharif season in many of its operational villages in the first year of the intensification programme. It also demonstrated changed practices in other crops such as paddy and millet. The following years saw a gradual rise in the number of new farmers adopting the new practices and crops as also the number of farmers securing better profit from farming.

A farmer from village Bade Kadma, Darbha Block tending to her bitter gourd plants

In the initial phase of the team’s intervention, the farmers barely had any market orientation. As is the case with subsistence farming, the investments in agriculture were minimal, of the order of Rs 5–7,000, during the entire farming season, including activities such as procuring inputs, hiring labour from outside the family, hiring machinery (tractors) and so on. The team carefully designed interventions that are market-facing, suitable to the agro-climatic conditions and which cause minimum disruption of traditional practices as well.

The team carefully designed interventions that are market-facing, suitable to the agro-climatic conditions and which cause minimum disruption of traditional practices as well.

T he plan was underpinned by a vision to address the area’s extremely pertinent issues of cash, food and nutrition insufficiency at the household level, and drawing the youth to agriculture. It underlined high-value vegetable farming in homesteads as a core intervention for securing the cash needs of a household. It further maintained that all other crops such as cereal crops, pulses and oilseeds would be promoted with no or little material inputs purchased from the market. For such crops, the use of local seeds, manure, etc., would be encouraged and a few of the conventional farming practices such as broadcasting, low use of farm-yard manure, quality of manure, and pest management measures would be changed to the extent possible. Given the demand for investment, rigour and intensity in the case of high-value vegetable farming, its area of cultivation was by design, limited to between 10–20 decimals of homestead land. Homestead land became an important piece of farmland that needed attention and further husbandry. As a result, installing irrigation facilities, and layering orchard plantations (such as mango and cashew) along with vegetable cultivation were listed in the menu of interventions. The remaining crops—millet, maize, oilseeds, pulses, etc.—were grown in the rest of the homestead and the uplands whereas paddy was grown in the levelled and bunded medium and low lands. All these were designed after careful consideration of the existing volume of the family’s labour-work and by observing past trends.

Vegetables grown by tribal farmers flooded the village weekly haats (bazaars) and were supplied to neighbouring and distant sabzi mandis (vegetable markets), something the tribal communities never dreamt of.

A chieving this, however, was quite a challenge. For a typical tribal farmer, especially a woman farmer, learning the necessary skill-sets to bring changes in her farming practices, appreciating and finally adopting these were no easy tasks; more so for the intervener, who was anchoring these shifts. The team employed multi-pronged strategies such as preparing videos that document success stories, disseminating these videos using pico projectors in the field areas, organizing mass exposure to demonstration sites, arranging credit from banks and NRLM grants for working capital, promoting agri-entrepreneurs to facilitate backward and forward linkages with the market, strengthening the pool of community service providers and resource persons for extension support to farmers, and so on.

Three years from the initiation, the team has reached out to nearly 5,000 women farmers with the above interventions; this includes 2000 farmers, who invested in high-value, vegetable crops across 40 villages in Darbha block. Vegetables grown by tribal farmers flooded the village weekly haats (bazaars) and were supplied to neighbouring and distant sabzi mandis (vegetable markets), something the tribal communities never dreamt of. The farmers ramped up their investments and secured additional cash income in the range of Rs 10–30,000 within a span of three months and, more importantly, have had their motivation growing. The results extend beyond the direct benefits to farmers. Many of the village youth, who acted as trainers under PRADAN, turned agri-entrepreneurs and marketed the produce in local and distant sabzi mandis.

Farmers adopting newer and more efficient technologies like using plastic mulch in Darbha block

Kharif Agriculture Interventions: Just a Launchpad

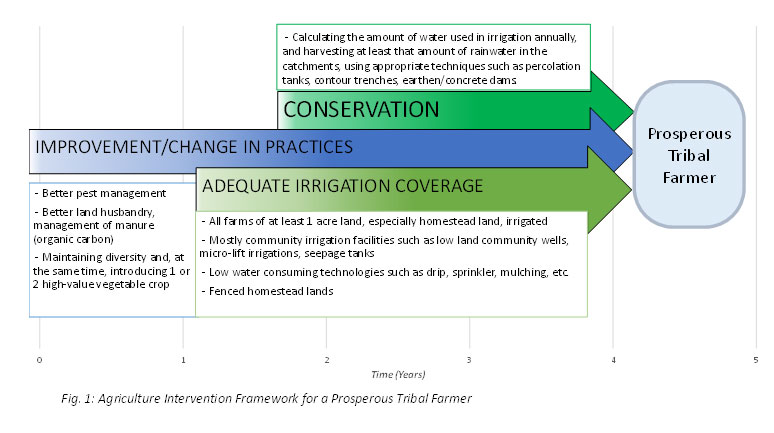

T he important learning from the above experience is that Bastar’s tribal farmers needed to become ‘farmers with some market orientation’. This requires promotion of a farming system that ensures marketable crop yields at levels much higher than the current ones (desirably with no/low chemical inputs) by changing some of the older practices and seed quality, and, at the same time, maintaining cropping diversity and not losing those local varieties that yield more or contain more nutritional values. When a family is assured of irrigation facilities, agricultural interventions can be started in the kharif season as well. In the tribal context, usually, the kharif season is a potential entry point for promoting improved agri-interventions and is also a launchpad for further interventions such as the creation of irrigation infrastructure, and convincing and readying farmers for winter and summer farming. Besides having some of the conventional practices improved/changed with some better land husbandry, one or two market-oriented, high value, hybrid or high-yielding vegetable crops in homestead lands are critical for boosting their annual income from farming.

Now that the community has learnt some new farming practices and has developed a commercial orientation vis-à-vis farming, the interventions around increasing irrigation coverage and conservation are increasingly being demanded and appreciated.

O ne or two experiences of significantly high production and return in kharif helped farmers gain confidence in farming as a potentially viable, economic activity. With the help of their peer group, they then started exploring ways to further improve their farming practices and make it more lucrative. This process has now enabled the farmers to embark on a positive spiral of growth from subsistence farming to commercial farming. This is the stage when the farmers are ready to go for the second and the third crops and have started aspiring for irrigation facilities, fenced homesteads, etc., to support these.

Interventions that Followed: (1) Securing Irrigation Facilities, (2) Conservation

I nterventions during the kharif season, as mentioned above, takes at least a couple of successful cycles to have the tribal farmers gain enough confidence to adopt them. The positive experiences in the PRADAN case motivated farmers to aspire for double cropping, and they started demanding irrigation facilities. The team worked, in coordination with SHG federations and block and district administrations, at surveying and planning for irrigation facilities across about 20 villages, which culminated in the approval of a large number of micro-irrigation projects by the government. Soil and water conservation works too were implemented under MGNREGA. Now that the community has learnt some new farming practices and has developed a commercial orientation vis-à-vis farming, the interventions around increasing irrigation coverage and conservation are increasingly being demanded and appreciated.

With still miles to go, such achievements in a hardcore tribal context hold tremendous significance and have generated many lessons from the perspective of making farm-based interventions attractive for farmers. This is particularly important in the current context when COVID-19-induced crisis will deter many of the regular migrant workers from moving out of their villages for work.

1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bastar_division

2 https://secc.gov.in/districtSummaryReport

3 http://fsi.nic.in/sfr2009/chattisgarh.pdf

4 https://www.pradan.net/

5 https://agriportal.cg.nic.in/agridept/AgriEn/KHARIF_17.htm#%E0%A4%AB%E0%A4%B8%E0%A4%B2_-_%E0%A4%9A%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%B5%E0%A4%B2