Which witch hunting?

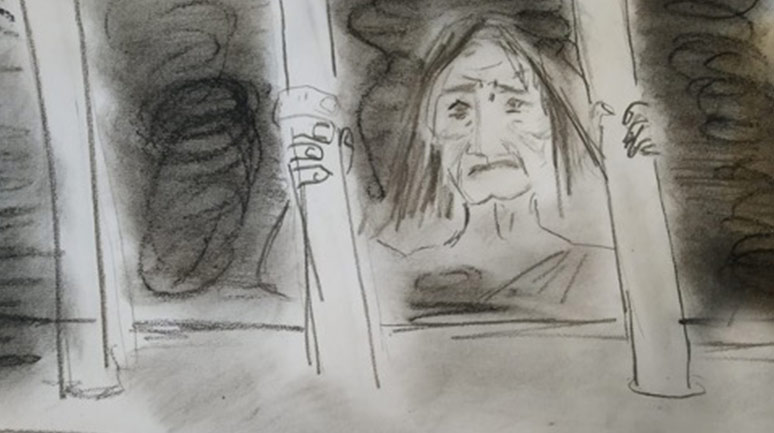

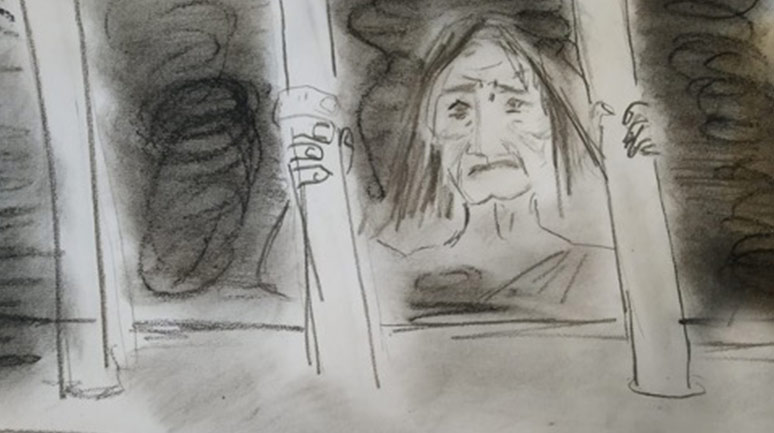

Image artist: Jayamala Iyer

“They all pinned me down, grabbed my arms and legs so I was unable to move and shaved my head while I kept screaming and begging them to let me go.”

Introduction

T his post is the first in a series of mapping the milestones of a current research project. The research is using a Critical incident methodology to capture change actions witnessed during a recent witch hunting episode in Jharkhand, as narrated by key people involved in it. The critical incident technique (CIT) is a research method in which the research participant is asked to recall and describe a time when a behavior, action, or occurrence impacted (either positively or negatively) a specified outcome (for example, the accomplishment of a given task). This post covers the research questions being considered and the possible directions for the research to explore.

The project idea emerged from a series of conversations and workshops on bringing Theatre of the Oppressed as a core practice in order to create shifts in perspectives and action w.r.t the practice of branding and hunting of women as witches in certain regions in Jharkhand.

The process begins with a recent case in Jharkhand where a woman was branded and publicly attacked and humiliated. The interviews are based on narrative practice and the first level design invited respondents to share their story of the ‘episode’ as they recall the process.

Methods: The stories were captured with the help of a Narrative Inquiry approach through phone conversations with respondents- Respondents interviewed so far: Survivor and member of her family; 3 Block Resource Persons (BRPs); 1 JSLPS (Jharkhand State Livelihoods Promotion Mission) Official.

As one approached the episode and the surrounding web of events, it seemed somewhat overwhelming and complex in terms of the different aspects of the experiences. It seemed useful to study the story /narrative as a unit in order to structure the experience and organise it into meaningful units.

The incident

T he survivor, Sukhwanti devi (name changed), was accused of causing the death of her older brother-in-law who owned a shop in the village. After the death of the brother-in-law the store had been shut for about a month and on the day of the incident, the owner’s 12-year-old son claimed that he saw the survivor inside the closed shop from the window. According to him, she then transformed into a black colored cat and disappeared. The child reported this back to the family and that’s when the family started to accuse her of ‘eating up’ the man and being a Dayan. They then gathered a crowd, and she was then beaten up, stripped and paraded in the entire village. The crowd also held her down and applied leaves that caused a burning and itching on the skin and shaved her head. She was then asked to pay a fine of Rs 1000 which she could not, and she begged to be allowed to go for Rs. 500. Her plea was granted, and she was released.

Within 3-4 days of the incident, the villagers collected signatures from 84-100 people approximately on a blank sheet of paper. An accusation of robbery was then written on the paper and given to the local police station so that the survivor could then be arrested for theft. Around the same time, the police received an anonymous call reporting the witch hunt incident following which the police went to the village and verified the occurrence of the event. They then asked the family to register a case without which they would not be able to investigate or take any action against the perpetrators. Sukhwanti devi and her son then filed a police complaint following which 9 arrests were made from the village.

The family received many threats after filing the report especially from the families of those arrested. It appears that the arrested people were soon released on bail and there has been no further event/follow up of the case.

Three weeks later..

O ne of the BRP women, Radha (name changed) from a neighboring village who is also in charge of the village of the incident accidentally discovered the news of the incident through the survivor’s daughter in law. She then spoke with a few more women from neighboring villages and together they went to the village to meet with Sukhwanti and verify more details. They report that they were not acknowledged or spoken to by anyone else except Sukhwanti and the daughter in law the rest of the village people ‘ignored’ their presence. In fact, at some point they got angry and a crowd got together and chased them out of the village.

It was then that Radha sought help from JSLPS officials and explored what action could be taken in response to the event and the lack of access to the survivor and the village. Together, they came up with the idea of organising SHG women with the support of other BRPs from neighboring villages in protest. They organised a meeting of 3 CLFs in a neighboring village and shared news of the incident and sought ways to respond. The group decided to organise a rally and marched to Kolebira (the block) to publicly organise a ceremony with the survivor and her family. They collected cash and sarees and presented these to Sukhmani in a public ceremony while performing the traditional rituals of worship for her. They asked for her forgiveness and sang songs and slogans against witch hunts. The village folks however gathered around but did not ask forgiveness or participate in these rituals.

Respondents also reported that subsequently, the families of those arrested offered an apology to Sukhmani and then demanded she withdraw her complaint, which Radha strongly advised her against.

Emerging issues to be explored

S ome facets of the narrative from different perspectives stand out as directions for deeper inquiry: Firstly, the immediate action of mobilising village folk after the incident and filing of a case of theft against Sukhwanti. Since people are aware of the law and the consequences of being involved in witch hunting, it is important to note that there was a swift reaction to cover it up. Secondly, the women from the SHGs were at the forefront according to all respondents interviewed so far. The respondents also mention that they heard the men folk asking women to take the lead since they would be protected and the consequences will not be severe for them (Aaj kal Mahilaon ka raj hai)- this brings forth the orchestrated, collective backlash against women with women as co- conspirators. This is especially significant since some of the women leading the attack on Sukhwanti were women who had been through training and awareness building processes on the issues of branding and hunting of women as witches.

There are many ways to begin a conversation to capture the events around a specific incident which is also referred to as the story. In one of the ways used in this research, the Narrative Inquiry approach, the researcher takes a position of inquiry and seeks to notice events that contradict the dominant story. In this case, one example may be the event when Radha made the calls to investigate the incident and get more details. Another is her efforts to organise a group of women around raising their voices and expressing disapproval of it. At a closer look, these apparently small events offer a glimmer of an action or of an intention that is at variance to the problematic story and fall outside the territory of the problem-story. The data collection process is currently focusing on capturing these from the various actors involved in the incident.

Conclusion and areas for future research

In a recent presentation with the Research Wing members team, some of the questions and insights raised by the team were:

- How do we as interviewers create a sense of safety and security so that the respondent is able to talk about such intense experiences and build our skills in this realm?

- Did the respondents express any fears or resistance in being a part of the study?

- The larger research question- can we have more information or insight into the reasons behind women instigating such acts despite so much awareness building interventions being implemented with them? What is triggering such cases to be happening?

- How are other women responding to such cases and what are their feelings and thoughts around these issues? capturing those would help.

- Such backlashes and then the integration of survivors including the person who flagged the issue into normal life is something we may want to investigate at a later stage.

- Police are not very supportive, so, what are the symbols which show that and why?

Going ahead, we plan to conduct more such interviews with some of the other people involved in this incident and analyse the larger data set identifying a primary research question from some of the questions presented in this post.

We welcome comments and reflections from the readers of this blog.