The Woman Farmer: Taking Ownership, Claiming Space

Having realised that they deserve to claim their space as farmers and that they are equally capable as men of taking sound decisions on agriculture, the women of Samnapur find strength in the organisation they formed, experiencing the power of the collectives intent and action

Mahila kisan activity in the Cluster Level Federation

“What’s the first thing that comes to your mind when you think about a farmer? Draw the image of a farmer on a chart paper.”

That is how the meeting of Matrashakti Ajeevika Cluster Level Federation (CLF) of women collectives in Samnapur block, Dindori district, Madhya Pradesh, started. Not surprisingly, none of the CLF members drew the image of a woman as a farmer!

The purpose of conducting this exercise with the members of the CLF was to make them realize that despite contributing to 70 per cent of the work in agriculture, they do not consider themselves farmers. This exercise was conducted in October 2019 on the International Day of Rural Women.

We then asked the CLF members to list out all the work they do in agriculture. They listed out all the work…from sowing seeds to harvesting the produce. All the activities, barring ploughing the field, irrigating it and selling the produce, were done by women.

We then asked, “Why is there is no woman in your drawing? Don’t you think you are a farmer too?” One of the CLF members exclaimed, “Society has created this norm. They say that women cannot hold the plough, it is a bad omen and leads to calamity. Jo khet jote wohi kisan; par kya khet jotne se hi kheti ho jaati hai? Baaki mehnat kaun karta hai? (The one who ploughs is supposed to be the farmer. However, does farming only involve ploughing? Who does the rest of the work?).”

Celebrating their collectives and planning to eat healthy food

The exercise helped the CLF members reflect on their role in agriculture. The women came together and asserted, “Meri pehchaan, main hoon kisan! (I am a farmer and this is my identity!).” Nine months later, in July 2020, the women registered the first all-women Farmer Producer Company (FPC) in Samnapur, and proudly called it Halchalit Mahila Kisan Farmer Producer Organisation (FPO).

“Ye mahila kisan ka sangathan hai…ab mahila na sirf kheti karengei balki apni pehchaan bhi banayengi (This FPO is for women…now we will not only do farming but also establish our identity). We named it Halchalit because we are no more afraid of holding a plough. We will break this taboo,” said Bhubaneswari Devi, member of the Board of Directors of the FPO.

From Farmer to Entrepreneur

“Hum log jab kheti karte the toh itna hi sochte the ki khane layak guzaara ho jaaye; baaki kharche ke liye toh majdoori hi karte hain (Earlier, our farming was limited to producing the bare minimum of what was needed to feed ourselves; for all other requirements, we would do labour work). We never thought that agriculture could be lucrative and we can earn enough from the fields. Today, my wife has changed my thinking,” said Gangaram from Dudhera village.

The women in Samnapur are slowly bringing about a shift in agricultural practices; they have more say and control over the decisions related to these practices. This change in their mindset is the result of helping women understand their role in agriculture, providing them with training on improved agricultural practices and leveraging various government schemes through women collectives. Women cadres are selected and trained as Aajeevika Sathi, Poshan Sakhi and Sansadhan Sakhi to reach out and support other women.

The women in Samnapur are slowly bringing about a shift in agricultural practices; they have more say and control over the decisions related to these practices. This change in their mindset is the result of helping women understand their role in agriculture, providing them with training on improved agricultural practices and leveraging various government schemes through women collectives.

Women collectives such as SHGs, Village Organisations (VOs)and CLFs became the forum for women to flag their concerns and discuss issues related to agriculture, crop planning, input supply, etc. Community cadres also attend these forums and provide guidance and support to the women farmers. Women have learnt techniques such as trellis farming, staking, disease and pest management, and preparation of organic fertilisers. As a result, there is considerable increase in the cropping intensity and land use. In 2017, there were 1,200 vegetable farmers in the block and significant effort was made to collectivise the entire system. Currently, in 2021, there are 1,600 vegetable farmers, who are being nurtured in production clusters. Over the years, the cost of production has increased for paddy. This is because of various reasons such as increased use of fertilisers, use of same seeds having disease, cropping practices, erratic rainfall and soil-moisture availability. Traditional crops such as millet and lentils which are more resilient to the vagaries of climate were re-introduced in the area. Simultaneously, farmers were trained on better cropping practices and managing disease and pest control in these crops. In the last one year (2021-22), 484 millet farmers, who collectively cultivated 484 acres, and 274 lentil farmers, who cultivated 274 acres, were collectivised to enhance production and to get a better price for their produce.

However, there were issues as well. Whereas production increased, the issue of getting quality and timely input supply at the doorstep proved difficult. Farmers needed to sell their produce at higher prices, to realise profits from agriculture. Initially, the block-level Federation in Samnapur would buy the inputs in bulk and provide it to its members.

CLF members then highlighted other issues. “We are now getting saleable produce from agriculture but we are facing problems in selling it. We sell the pulses at Rs 35–40 per kg whereas it is sold in the market at the Rs 80–100 per kg. We want that our produce is sold at market rates and the vendor picks up all the produce from the village itself.

“Only paddy is sold at the minimum support price (MSP) and that too for farmers, who are registered. If we enter the process of registration, we miss the time for selling. Many women cannot sell their paddy because of this. And we produce many crops such as kodo kutki (millet), pulses and vegetables. If we do not get a good price, why should we invest our time and resources in producing it?”

This led to a discussion on forming a producer collective, which would solve the problem to some extent. However, there was need for an independent body that would provide end-to-end services to farmers such as timely inputs, technical guidance and market linkages, to realise better prices for their produce.

Starting a Women FPO

When the women articulated the need for forming a producer collective, we (the PRADAN team) in Samnapur introduced the CLF members to the idea of FPOs. A series of orientation training programmes were held for the CLF members on what an FPO is, how it is promoted, who its members are, who its shareholders are, what are the benefits of forming an FPO, the roles and responsibilities of an FPO, etc.

FPO logo

The CLF members and the PRADAN team then conducted such orientation meetings in the VOs, in which all the farmers—men and women—participated. A sizeable number of farmers gave their consent to forming an organisation that would ultimately benefit them. Simultaneously, the process of forming an FPO and registering it under the Companies Act 2013 as an FPC was initiated. Twelve board members, who had shown leadership skills and were prepared to take up the challenge, were identified.

The task of the Board members was to reach out to the women farmers across Samnapur and convince them to become members of the FPO. One of the focus areas of the FPO was to include farmers from the Baiga Chuk region of Dindori district. This region is predominantly inhabited by a Particularly Vulnerable Tribe Group (PVTG) called Baiga.

Of the 44 villages in the region, 18 villages are in Samnapur block. The farmers in these villages are not exposed to chemical farming practices. Millet is the main crop grown in the region.Productivity in the area is less and it is very poorly connected to the market. Thus far, traders went to the villages and bought the produce at minimal rates.

To mobilise and orient farmers to become members of the FPO, its Board members and PRADAN organised 30 shareholder camps in 2020–21. In these camps, SHG members from different villages visited the company office, where they were provided information about the basic functioning of the FPO, its services and benefits to farmers.

We may not know many of the technical and legal terms used in the FPO; however, the basic purpose of promoting the FPO was to remove middlemen and provide direct benefits to the farmers. Farmers are provided support at their doorsteps, be it inputs, technical support or selling of their produce at market rates. And at the end of year, all the shareholders are provided with information about the benefits the company has earned, explained Draupadi, a member of the Board of Directors of Halchalit Mahila FPC.

The basic purpose of promoting the FPO was to remove middlemen and provide direct benefits to the farmers. Farmers are provided support at their doorsteps, be it inputs, technical support or selling of their produce at market rates.

Having started with 13 promoters, the FPO now has 917 shareholders from four CLFs of 51 villages in Samnapur block!

The FPC has recruited four field staff, to provide handholding support to farmers at every stage. They engage in planning and indenting in every season with the shareholder group in the village, on the basis of which the FPC arranges inputs.

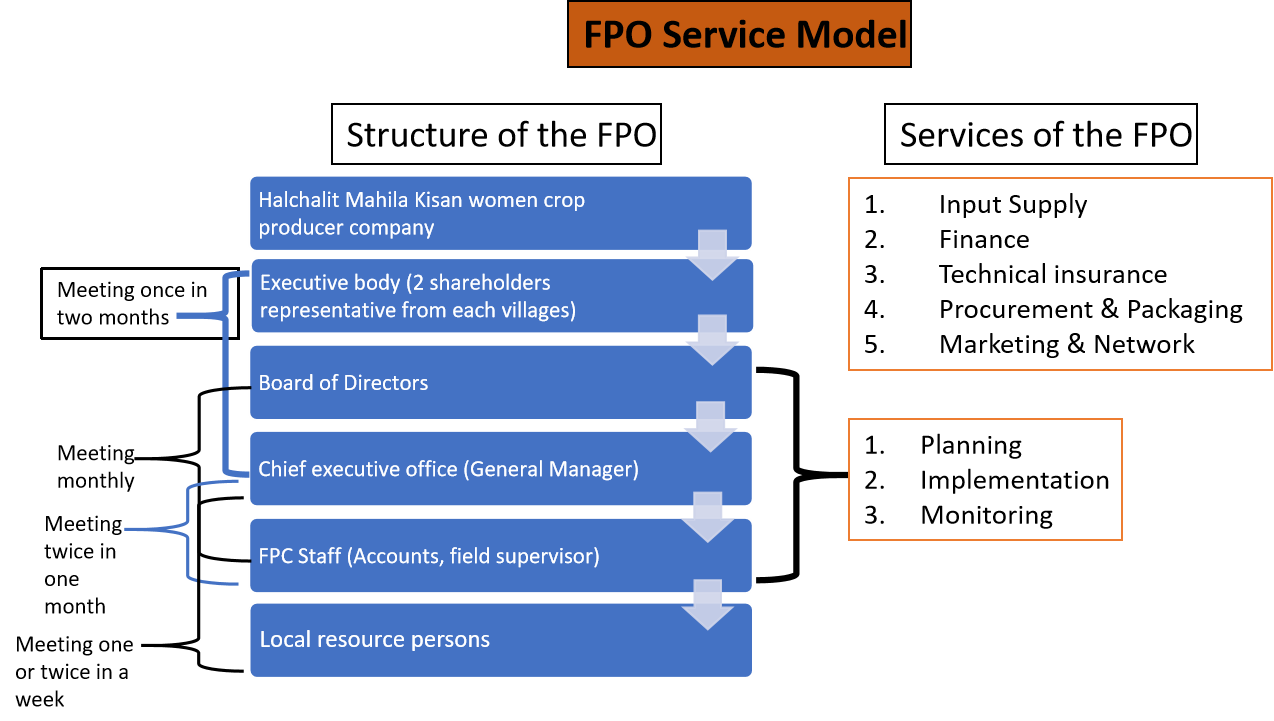

FPO Service

Identifying millet as the main product of the FPO

Traditionally, farmers in Dindori grew diversified crops such as pulses, oilseeds, paddy, millet, maize, wheat, pigeon pea and lentils. Over the last few years, however, there has been a shift in the cultivation pattern, and farmers are increasingly opting for monocropping paddy. The reason being the farmers can sell paddy at a decent MSP and the other crops are not supported by MSP. Approximately, 25–30 per cent of the total production is consumed in the households and the rest nearly (1500–2000 MT) is sold to middlemen and big traders at very low rates; kodo millet is sold for about Rs 12–15/kg and kutki millet for Rs 24–28/kg.

PRADAN conducted a market study (in December 2020) with 408 farmers from Samnapur to understand the scope of millet cultivation. Farmers were found to get Rs 15–20/kg for kodo millet whereas the retail price after sorting, grading, processing and transportation is Rs 50–53 per kg and its price in the market ranges from Rs 100–180/kg. The survey helped to understand the huge scope in the production and marketing of millet.

Initiating partnerships to promote millet

As per the baseline survey done by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), there exists a high level of malnutrition in Dindori district. The average Body Mass Index is 18.5 kg/m2 and the prevalence of anaemia is very common. The multi-dimensionality poverty index for Dindori district is 0.278.

This required that the FPC not only focus on the marketing aspect but also on encouraging the women farmers about including nutritious food in the diet. Millet production had decreased over the years primarily because of the impetus on paddy. Other factors such as the unavailability of processing units, a decreased demand of millet in the local market and the lack of favourable government policies on millet affected production.

PRADAN attempted to introduce millet both from the nutritional point of view as well as for its market value. Mass awareness programmes were conducted on the cultivation and consumption of millet in the area. However, significant external support was required to give millet the push it required.

The much-needed stimulus came from its partnership with Indian Council of Agriculture Research–Indian Institute of millet research (ICAR-IIMR). IIMR provided the initial management cost, technological support, connecting the FPC to millet markets for output linkages, and linking the FPC to other financial institutions such as Small Farmers Agribusiness Consortium (SFAC) and Samunnati for working capital and credit support.

With the support of IIMR, the FPC has installed a millet processing unit (to promote millet consumption) that will process the raw millet into an edible form, easily available to all. This is where millet producers can sell their produce and also where millet consumers can avail of it. Also, the value addition in millet such as cleaning, sorting, grading, hulling and processing provide a good profit margin to the company.

The green shoots

“Things are a lot more convenient for us now. We don’t have to struggle to get seeds and fertilisers. We receive all the services at our doorsteps even during the lockdown. We now have a system by which we can buy inputs, get training and sell our produce. There is no tension. Added to this, we will get a share of the profits. What else can one want?” said Pawanti Kushram, one of the shareholders, during the first annual general body meeting of the FPC. The event was celebrated by more than 500 shareholders on September 28, 2021.

FPC President Godavari Maravi addressing the shareholders at FPC's first Annual general meeting

In the first year of its formation, the FPC had a sales turnover of Rs 9.5 lakhs, earning a profit of Rs 9,300. Meanwhile on 17 September 2021, the FPC received the ‘Best Emerging FPO–Poshak Anaaj Award’. The award was presented by the Central Agriculture Minister, Shri Narendra Singh Tomar, for its exemplary work in growing nutritious crops and helping marginalised farming communities. Organised by ICAR-IIMR, the award was presented in the Nutri-Cereals Multi-Stakeholders Mega Convention 3.0 A Curtain Raiser for the Upcoming International Year of the Millet–2023 at Hyderabad International Convention Centre, Hyderabad.”

Key learnings of this experiential journey so far!

Currently, the FPC is at a very nascent stage. It has engaged in end-to-end linkages in vegetable cultivation, including the procurement and the marketing of millet, and has now started engaging in lentil production. The FPC supports farmers in crop planning, providing input services and providing crop management support. The focus is on promotion of non-chemical-based, regenerative farming practices. Bio-fertilisers and bio-pesticides are also available through the FPC at the doorstep.

One of the major challenges that the FPC faced was the competition in the market, and providing fair and profitable prices to its shareholders. This kharif season, when the FPC released its input price of Rs 940/25kg bag (for paddy seed), many of the vendors lowered their paddy seed rates to Rs 920/25 kg bag from Rs 1000/25kg bag. Also, emulating the FPC, their competitors started providing doorstep support.

FPO shareholders with Best emerging FPO award

Farmers, however, are owners of the company. The initial orientation and discussions worked well. “The traders are scared that if the FPO runs successfully, they will not survive. Therefore, they have lowered their prices. We must all remember that they just want to break us. We will not succumb to their ill practices. We can’t abandon our FPO for just Rs 20. We will profit if our company grows because we are all shareholders,” said Samaratia, a shareholder from Paudi Ryt village.

“However, in the long run, we will have to demonstrate something huge that will motivate farmers to associate with Halchalit Mahila Kisan women FPO; we will need to work on end-to-end conversion, including timely input availability alongside production planning and market support to shareholders while keeping them aligned with technical advancement. The plan is to engage with each shareholder in two seasons (in both cereal and pulses) annually so that we can contribute to a significant increment in their agricultural income of nearly Rs 50,000 per year. For that, the FPO will need a sound business plan. Preparing a robust business plan is critical to ensuring it has targets to achieve, in terms of sales volumes, makes an estimate of costs and keeps it under check, and establishes a system of value addition, to get maximum profit from its produce (especially millet and pulses).

“With the experiential journey of the past 17 months, one thing we have realised is that the farmers trust and accept what they see, and stick to the commitment we promised; we need to work hard to provide the desired services to the farmers,” said Godavari Maravi (President, FPC).