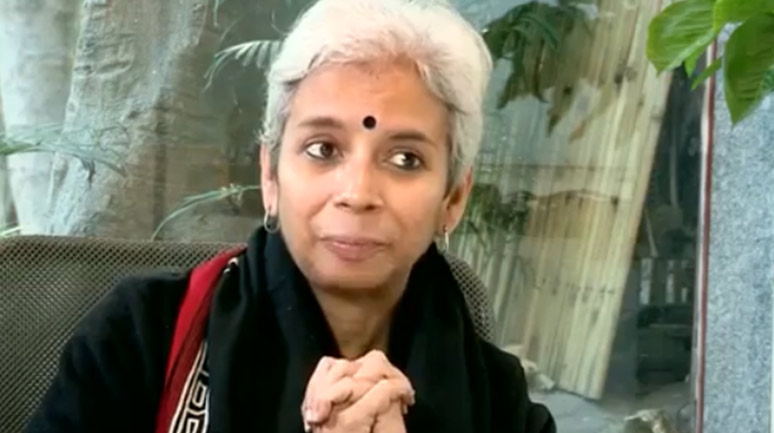

Interview with Sushma Iyengar

Sushma Iyengar is a social activist and a recipient of ‘Gondhia Award for Social Work’ in 1996, instituted by Young Men’s Gandhian Association. She founded and led the Kutch Mahila Vikas Sangathan, an organization of rural women, initiating processes for mobilizing, organizing and training rural women, as well as organization building. Her other organizations, SETU—a network of 18 grass-roots, resource-facilitation centres in clusters of 15–20 villages across the district of Kutch; K-LINK—an information communication technology organization, which works to make ICTs accessible, and applicable to developmental needs; and Khamir, an organization that works for the empowerment of crafts people.

To be in a process of change and transformation, especially with the most vulnerable, it changes you. You become a better human being and develop the ability to reflect, watch and list.

She leads transformative action in the areas of gender justice, cultural identity, traditional livelihoods and local governance. She is also a co-founder of the Kutch Nav Nirman Abhiyan, commonly known as Abhiyan, a district network of developmental, civil society organizations in Kutch district of Gujarat.

Sudhir Sahni is in conversation with Sushma Iyenger.

Sudhir: You did your Masters in English Literature and in Development Communication. You then came back to work with women at the grassroots in Gujarat. Did you have that in mind even before you left? What was the inspiration?

Sushma: Yes, I went with the idea of coming back. The early 1980s was an interesting time in India. The women’s movement was just coming into being. A lot of iconic films by film-makers such as Shyam Benegal were released in that time; so there was a new consciousness growing. As young students and teenagers, one was suffused with that too. I was studying English Literature and I think it creates compassion. It is about looking at society; literature is actually an expression and record of the times. An interest in wanting to do something with women, a fit of great anger against the patriarchal world that we lived in and wanting to change that was growing in me since high school. I realized that Literature was limiting. It did not train me to jump into activism. That’s when I moved to the next course and program, thinking that I must train myself into a more journalistic mode. There I got influenced, got exposure to a more evolved understanding of gender issues. That’s when I got more determined to come back and work directly with communities and women.

Sudhir: What were the challenges you faced on coming back?

Sushma: The first challenge was to gain trust. I began my work at the border and people at the border don’t trust very easily. Multiple security agencies were functioning there—the army, the BSF and the intelligence. Smuggling activities were happening and, therefore, they didn’t trust me at all. They tested me in every interaction, to as certain if I was also part of some intelligence agency. When I ventured into the village, the villagers were very hospitable but would avoid attending a meeting or work, which is what I wanted to get into immediately. I would be eager to start work but they were keen to send me back. Because of my short hair and slim physique, they thought of me as a man from the intelligence agency, disguised as a woman. My team and I would be under scrutiny and word would travel around the villages; by the time we got to the next village, they would also know that we were coming and we would not be welcome. The trust factor took some time to establish. Language was also a barrier—because I spoke Gujarati, not the local Kuchhi dialect. The long-term challenges were getting women out of their homes. There were conservative communities, and women were not allowed to leave their village. And we would ask them to come for training in other areas by bus. We needed to break through the mistrust of the men about what we were planning to do with the women. The main challenge, however, was to get the women to find themselves, to find their own identity and take on the immediate patriarchy, which they were surrounded by—their families. It is easy to take on the world but not your families. Added to this, we were being watched closely by the citizens of the region and the political representatives and were accused, at times, of breaking people’s families.

Sudhir: Would you like to share about some of your early successes that strengthened your resolve?

Sushma: I think there were many milestones on the journey. The earlier milestones were when we got women to start looking at their ecological resources, their land, water issues, etc. That was a realm that women had never engaged with although they bore the brunt of any drought and the lack of water. Rain, clouds and water were the determining factors in their lives. They did not influence it nor did they have any decision-making space at all for this. This was an interesting milestone in the transformation of women’s lives. If the power dynamics within the house and family have to change, they first have to get into the public space and take on issues such as water and land. Although women are not the decision-makers, they have deep knowledge systems because they constantly engage with the land and the biodiversity. Taking these women to the decision-making space unleashed a kind of power dynamics we did not anticipate.

The more strategies we tried, to create a discourse among them about their power equations and the structure of gender roles, and how to break out of them, the larger community and the panchayat would think of ways to counteract and nullify our efforts. When that happened, women would be discouraged and would back off because they did not want to change the dynamics in their families. We would take measures to prevent that from happening in families; and as time passed, we started noticing a curve of change. During drought relief activities, women started playing an active role. There were some dry talaab/lakes, which the women took complete responsibility of bringing water to, handling logistics, etc.

In 1998, ten years after we began, we initiated a community radio programme; that was the first community radio programme in the country. It was run entirely by women’s collectives. Many of their stories, their successes, their struggles, their issues were scripted and it was broadcast as a series on All India Radio for one year. The serial became so popular that the district demanded it to be run for another year and financed it. The stories were heard in the region and beyond, and they had voices that were reaching far and out. This actually created a movement for community radio.

Sudhir: How did this appreciation come about?

Sushma: Some eminent people from our country came and helped the women we were engaging with. This was a highlight for all of us, to see change happening and to see the community finally accepting it and taking part in it. Women’s sense of self and identity started changing when they started getting appreciation from the community and the region. Instead of getting them into mainstream women’s issues first, we brought them into the public space. This movement was required in the region of Kutch; and it got a lot of support from the administration, lawyers, traders and citizens because it was a revival of the water systems by the women. The large shifts started happening after the water movement. Our objective was not to form an SHG but to educate women about banking systems so that they eventually set up banks at the block level, transacting, getting trained and training banks on how to engage with women. After 1992–93, women started coming into the panchayat. (https://www.facebook.com/pradanofficialpage/videos/1622607114460003/)

In 1995, the Beijing Conference brought together many women’s groups. There was a huge environment for inspiring and getting inspired. The earthquake in 2001 changed many things for many of the communities, created a lot of opportunities and also broke many barriers. It allowed people to start redefining their lives. In a disaster, the state is open; everyone is far more open because policies need reform. Old conflicts turn around. When human beings are vulnerable, they are open to change. When you are successful, you may think you are independent. In times of vulnerability, people are interdependent. Indeed, conflicts can also get heightened during disasters; nevertheless, they find solutions as well. Leadership stepped up. An iconic symbol for us is the ‘Saras Crane’. Every winter it comes to Kutch from Siberia; it always flies in a ‘V’ formation, rotating their positions. When the last one has revived its energy, it takes the lead. This is such a beautiful symbol of transferring energy and rotational leadership. (https://www.facebook.com/pradanofficialpage/videos/1614319461955435/)

Sudhir: Do you think the scale of women’s involvement is larger now?

Sushma: I think there are more challenges now; it’s a cycle and it’s allright for challenges to come our way. It was important to create inclusive spaces for women, and that’s what the women’s movement in India did at that time—in urban and rural. The current scenario is a mixture of both; there are many women still living in ‘purdah’, for whom nothing has changed; and there are women for whom a lot has changed. Many women have broken barriers. I find women today in rural areas are very expressive, mobile, able to take on issues, and not completely bound at all. It is always our inner demons that are most difficult to navigate. Economically, it has become a very complex world. Culturally, we are breeding intolerance and hatred and it is spreading to inter-faith and ethnic politics. Women are not in a secure space. Women are subject to a far more complex environment when they move out of their houses. Their ability to deal with that may be improved but their sense of being has taken a thrashing because the aggression in their external world is coming back to domestic violence, bodily aggression. In a community, leadership patterns have changed, everything has become more political. It is a double-edged sword—there are traditional patriarchs or there is a benign leadership that would act against violence in homes, fights, etc., but that latter kind of leadership seems to have disappeared. Therefore, I think the challenges for the younger generation of change-makers is higher. And, the need for grit and perseverance is more.

Sudhir: What is your message to youngsters venturing into the development sector?

Sushma: You need patience for transformation. What I’m finding interesting with the younger generation is the amount of creativity and application they are bringing into looking at problems, addressing issues and the resources at hand. Their commands are higher. Many people are thinking laterally on issues, which is the good part. To be in a process of change and transformation, especially with the most vulnerable, it changes you. You become a better human being and develop the ability to reflect, watch and list. One can achieve great things internally as well as externally. And for today’s society, that’s important. (https://www.facebook.com/pradanofficialpage/videos/1629471130440268/)