The Changing Farmlands of Darbha

Raymati Manjhi with her produce

Adopting simple and affordable technologies is revolutionizing smallholder farming from mono-cropping to cultivating commercial crops in this poor tribal block in Bastar district of Chhattisgarh

“We had 4 acres of land but it never produced enough to sustain our family of six. My husband had to migrate to different cities in search of work and I did menial jobs locally. Today, after three years of learning new methods of agriculture, our same land is producing enough. We are farmers now.”

T hese are the words of Raymati Manjhi, a proud farmer from Darbha tehsil of Bastar region. She belongs to the Halba tribal community and lives in Alwa village. Like Raymati Manjhi, 2,000 families have embraced better agriculture practices and technologies to increase their land productivity.

Nestling in a picturesque landscape, Darbha tehsil is replete with natural beauty. The green of the sal forest and the blue streams attract many visitors to this region to enjoy its scenic beauty. The natives of Darbha, however, migrate to the cities in search of labour. Darbha is primarily a tribal area inhabited by tribes such as Madiya, Dhuruwa and Halba. People are dependent on agriculture, forest produce and livestock rearing for their livelihoods. The average landholding of the farmers is about 3.44 acres (as per the Institute of Financial Management and Research study) and the area receives high rainfall of 1,450 mm (India Meteorological Department, Ministry of Earth Science). Despite the rich resources, the people of Darbha are not able to satisfy their hunger. According to the Socio Economic and Caste Census (SECC) data (2011), more than 50 per cent of the children below five years are underweight and almost 70 per cent of the women of the reproductive age suffer from anaemia.

Alwa Village Homestead: An Ariel View

P RADAN has been working in Darbha since 2011 and has mobilized women’s Self-Help Groups (SHGs) and Village Organizations (VOs) in the region. During the interactions with the SHG members, one of the major challenges that emerged was that the farmers had minimal exposure to farm-based technologies and scientific methods of farming. The tribal community in Darbha cultivates crops only for its household needs and not as an enterprise, despite having sizeable landholdings. Primarily, the villagers grow paddy, maize or millet and do not have the know-how on how to cultivate commercial crops such as vegetables. There are other factors as well such as poor quality of land, low irrigation coverage and lack of access to credit that hinder farmers from adopting newer practices.

The situation, thus, required a different approach; the tribals of Darbha neither had the means to venture into commercial agriculture nor any technical know-how. Whereas there was increasing scope of agriculture in the region, the intervention required a change in the eco-system encompassing technical know-how, access to services and credit as well as market linkages. PRADAN has incessantly tried to develop that eco-system in Darbha block because of which the farmers are now more confident, better aware and adopting to better and environment friendly technologies. Some of the interventions for developing the eco-system in Darbha in the past three years are as follows.

Training locals to train the farmers

Many of the farmers were hesitant to venture into commercial farming. Therefore, a few pilot patches were identified; these would become the immersion ground for the farmers. Local community members were identified for training by the VOs. These members underwent the agriculture training conducted by PRADAN. Initially, a four-day residential training was conducted; later, a more comprehensive 20-day modular training programme was developed, with components such as class-room training, exposure to other immersion sites, on-field demonstration and market orientation. Darbha has a low literacy rate and getting participants with a minimum level of education was a challenge. Hence, the training modules and curriculum were redesigned. Pictorial and audio-video training aids were developed for ease of understanding. Pictorial information, education, communication (IEC) material was developed to help the trainees educate the farmers in the community. These trainees were provided with regular handholding support in the field by PRADAN practitioners. At present (in 2020), there are 50 community trainees in Darbha tehsil and each one handholds 80–100 farmers in a village. Of the 50 villagers trained, 32 are women.

Training and Capacity Building Sessions for the Farmers

Technical training and exposure visits for farmers

I nitially, it was difficult for tribal farmers to change their practices. Many of them were resistant to these changing methods. Exposure visits to pilot villages were organized in large numbers. Success stories were documented in videos in the tribal languages and shown in the villages with the help of pico-projectors. Pictorial tools, flex and flip charts were also used to motivate farmers. Technical training on simple and affordable yet effective farm-based technologies and farm-based practices were introduced. Technologies like stacking and trellis, pit and raised bed, mulching, protected crop nursery were demonstrated. Trainings in the preparation of organic pesticides and fertilizers were held. To further strengthen the training and capacity building process, a Farmer Field School was established in Dhodharepal village. Here, a residential training programme of five days was provided by experienced community trainers. In farm field schools, the farmers understand the causal effect of different scientific practices, diagnose the issues and find practical solutions. On-field practice and market exposure are the major components of the training programme. Looking at the effectiveness of the farm field school, three more such schools will be established in other three clusters. In the past three years, more than 900 farmer training events have been organized and more than 8,000 women farmers have been trained.

Asmati Didi, Hiramdeyi SHG, working on her homestead

Doorstep input availability

E nsuring on-time quality inputs at farmers’ doorsteps was a challenge. Women’s Federations identified experienced community trainers as Agri-Entrepreneurs (AEs). These AEs were groomed and handheld as entrepreneurs to start their venture. VOs provided the initial capital as loan from their Community Investment Fund (CIF), a grant received under the National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM). The AEs have links with the market; they explore the markets and purchase inputs as per the demand generated from the farmers. They deliver the inputs at the farmers’ doorsteps, after deducting their margin. Besides providing for input supply, AEs also pick up the produce from the doorsteps for marketing. In Darbha block, three of five women are actively engaged as AEs.

Somi Baghel (AE) selling her inputs

Farmyard manure application: Small but crucial intervention

O ne of the most crucial interventions was the introduction of the organic practices. Tribals in Darbha had no exposure to chemical-based farming and when PRADAN started intervening in the area, one of the important considerations was that the area should not be exposed to chemical-based farming. However, the existing practices were not effective. People would throw the cow dung directly into the fields without processing it. The collection of cow dung and urine, its composting and application with sufficient quantity was not in practice. Farmers were made aware about the importance of composting and its importance in soil productivity. Compost pits, vermi and nadep tanks were constructed at the homestead lands. “Ek khodra, ek tagadi (One pit, one tasla)” was the slogan to ensure its application in the optimum amounts. Trainings were conducted on how to make bio-pesticides and bio-fertilizers with locally available material. Training programmes were also conducted for farmers on how these should be applied in the field. In farm field schools, farmers observed the causal effect of bio-pesticides in controlling disease and pest attack.

Preparation of vermicompost

Market linkages

A s the produce increased substantially, linkages were established with bigger markets in Jagdalpur, Raipur, Dantewada, etc., so that farmers got a reasonable price for their produce. To establish a system around this, villages were divided into six Clusters; each Cluster caters to, on an average, 350 farmers. Micro Production Arrangements (MPA) were developed at the Cluster level, wherein all the farmers bring their produce on a designated day. The aggregation, weighing, sorting, grading and packaging of the produce is carried out by AEs. The farmer is paid for his share in the produce after deducting the commission of AE. The AEs carried out this whole process and were monitored by the Cluster-level Federation (CLF). This set the platform for the formation of the Agriculture Production Cluster (APC) and the Farmers Production Organization (FPO). This made the intervention sustainable and managed by the community.

Packaging of vegetables for marketing at the Alwa Aggregation Centre

Access to government programmes

T hese methods of farming require investment by the farmer. Convincing farmers to invest and mobilize their own money for agricultural inputs was a big task. Regular meetings with the farmers and the positive impact of the intervention helped to mobilize community investment. Small credit through NRLM-supported funds such as the Bank Linkages Fund, Revolving Fund (RF) and CIF were mobilized, to support farmers to invest financially in agriculture. Besides, linkages were established with different departments such as MGNREGA, Horticulture Department, District Mineral Foundation, CREDA, SCA and other allied departments for rural assets generation such as farm ponds, solar lift irrigation, orchard development, cattle-proof fencing, and goat and poultry sheds. Gradually, activities such as Horticulture, Backyard Poultry (BYP), and irrigation infrastructure through community participation and government convergence were carried out.

Bagal in her homestead land at the lift irrigation outlet

M odern technology with existing best practices of farming is strengthening rural economy. After the initial resistance to new methods, the tribals from Darbha have now adopted changes in their agriculture practices. Gradually, more and more farmers are leaning towards these new practices. In the last three years, the intervention has expanded at a significant pace, and has been adopted in all the villages of Darbha tehsil, including interior and forest villages such as Koleng, Chindgarh, Kakalgur and Toynar.

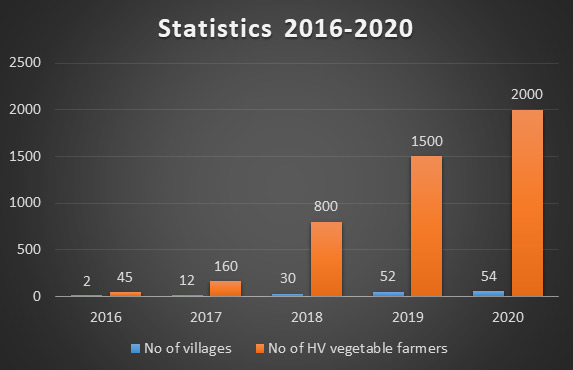

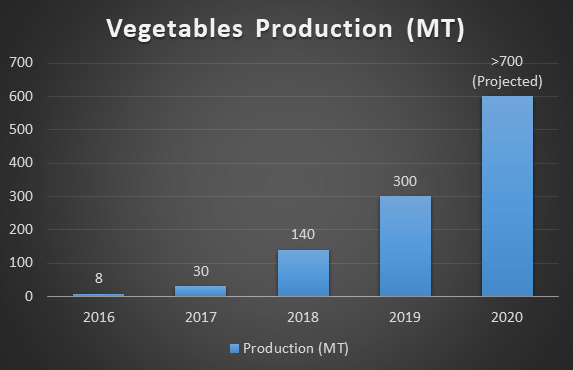

The following charts show the impact of these interventions, in terms of number of villages, farmers and production (MT), with incremental income in the range of Rs 5,000–50,000, depending on the size of the farm.

Lachani with her produce

R aymati Manjhi and many other women feel respected in their village and community because they played an instrumental role in bringing attitudinal changes in the mindset of the community. They are now involved in the different stages of agriculture, which had never happened earlier. The impact is not only visible in the increase in productivity and income but also in the food consumption of the households. Their diet has improved, with the consumption of diverse vegetables at greater regularity and in larger quantities. Raymati Manjhi says, “Aage har haat saag sabji ghento kaaje 800 jasan kharchaa hote rali, lekin ebe aamke aamcho baadi le hi khaato kaaje taajaa sabji mire se. (Earlier, we used to pay around Rs 800 per week to buy vegetables from the market; now, we get enough vegetables for our household intake from our own land).”

This year, despite the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, large-scale vegetable cultivation was done by around 2,000 farmers because they had access to inputs as well market linkages.

Purni Manjhi, Santoshi Mata SHG, Alwa: Mango orchard layering in her homestead

Way Ahead

I ncreasing modernization in different aspects of life demands a much higher income than what the tribals of Darbha block ever had. This makes the innovation and introduction of modern farm-based technologies in agriculture and allied sectors an important step in meeting the increasing expenses of villagers. The circumstances that emerged due to COVID-19 also demanded the same. The impact of modern agricultural technologies on the lives of poor and tribal farmers such as Raymati Manjhi in Darbha indicates the importance of bringing such technologies to the most-backward farming lands. It will help build a self-sufficient and vibrant village economy.