Scaling up Gram Panchayat Organization Development: The Way Forward

S INCE 2015, PRADAN AND ANODE Governance Lab are implementing the Gram Panchayat Organization Development (GPOD) framework across 15 panchayats in Jharkhand and 10 in Madhya Pradesh.1 Gram panchayats (GPs) are constitutionally recognized units of democratic governance vested with the responsibility of economic development and social justice. It needs no reiteration that, despite this recognition, even after 25 years, in most states—Madhya Pradesh and Jharkhand being no exception—GPs are far from being autonomous, democratic units of governance steering economic development and ensuring social justice. This context provides the rationale for the Gram Panchayat Organizational Development (GPOD) framework. It aims to strengthen the organizational capacity of GPs. Conceptualized as a process and a journey, the GPOD framework aims to address systemic issues within the panchayats, using the philosophy and principles of organization development (OD) and behaviour. Foregrounding the GPs as a unit of analysis and intervention, the framework recognizes the members of a GP—the functionaries as well as the elected representatives—as primary agents of change. Two years since, there is a conviction in working collaboratively with multiple stakeholders, to contextualize and implement GPOD to strengthen GPs as organizations and institutions of selfgovernance, having the potential to emerge as centres of excellence.

Two years since, there is a conviction in working collaboratively with multiple stakeholders, to contextualize and implement GPOD to strengthen GPs as organizations and institutions of selfgovernance, having the potential to emerge as centres of excellence

GPOD through SPACE

T he framework is being implemented as SPACE (Strengthening Panchayat Actions for Community Empowerment) in the two states. It involves an active engagement with multiple stakeholders. These include management and development professionals, state and district governments, grass-roots practitioners working with NGOs and CBOs and, last but not the least, elected and executive members of GPs. The latter are the most critical and should necessarily display an interest and the will to improve the functioning of GPs.

The framework entails an iterative step-wise process (translating into a journey) that GP members embark upon to strengthen themselves. In doing so, it simultaneously draws upon and embeds the legal and statutory provisions to engage with GPs. For instance, a starting point of the engagement is a bi-partite MoU between the GP and PRADAN, expressing the willingness to engage. This is premised on the state Panchayati Raj Acts, recognizing the GP as a body corporate having the powers “to sue and be sued as well as the power to acquire movable or immovable property and to enter into contracts.” (Section 11 of the Madhya Pradesh Panchayat Raj Avam Gram Swaraj Adhiniyam, 2001)

Following the signing of the MoU, GPs are facilitated into a process that underlines the need to simultaneously differentiate and integrate its components as an organization: vision, organization structure, incentives, resources and action plans. Ultimately, GPs are encouraged to plan for and implement solutions to identified pain points. This essentially translates into GPs initiating action-planning with individual GP members, taking on the onus of delivering on select functions. The objective of the process and the journey is to encourage GPs to move from sporadic fire-fighting to process-oriented functioning. Gradually, GPs are facilitated to establish and strengthen structures and systems that bring in accountability and transparency in their functioning, through a pro-active division of work and responsibility.

Two years since, there is a conviction in working collaboratively with multiple stakeholders, to contextualize and implement GPOD to strengthen GPs as organizations and institutions of self-governance, having the potential to emerge as centres of excellence. Over these two years, the intervention has resulted in several tangible and intangible movements that enhance a belief in the appropriateness and applicability of the framework.

Tangible results include the opening of Panchayat Bhavans, regularizing GP meetings inclusive of recording attendance, minutes and decisions, setting an agenda, and maintaining the requisite registers that mark an active GP

There are GPs in both the states that have moved to a stage where they are taking decisions and planning actions around larger deliverables that aim at systemic solutions. For instance, GPs have identified deeper intervention and focussed engagement with challenges related to education, agriculture and MGNREGA. To resolve these challenges, GPs have been facilitated to establish and activate corresponding GP structures as prescribed by the law, namely, setting up Standing and ad-hoc Committees.

The intangibles include collaborative decisions around recurring issues, enhanced negotiation skills while engaging with block and district Two years since, there is a conviction in working collaboratively with multiple stakeholders, to contextualize and implement GPOD to strengthen GPs as organizations and institutions of selfgovernance, having the potential to emerge as centres of excellence 53 panchayats, better conduct of the gram sabha (GS), etc. This visible movement of GPs towards debating and thinking collectively and working collaboratively, evidences the relevance of this framework in strengthening governance at the grass-roots. This visible movement of GPs towards debating and thinking collectively and working collaboratively, evidences the relevance of this framework in strengthening governance at the grass roots.

This visible movement of GPs towards debating and thinking collectively and working collaboratively, evidences the relevance of this framework in strengthening governance at the grass roots

Way Forward: Emerging Imperatives

W ith the first phase of the SPACE project nearing completion (the initial agreement with PRADAN is for 2016–18), there are two emerging imperatives that merit mention. First, how do we internalize the learnings from the field to further enhance the applicability of the framework? Second, how do these learnings inform the way forward in GPs wherein the engagement is ongoing? That two years is too short a time to expect dramatic changes on the ground needs no reiteration. As was rightly remarked by one of the PRADAN professionals, “A 25- to 30-year history of de-capacitating GPs cannot be reversed in a two-year period. Strengthening GPs as units of self-governance is much required and calls for long-term sustained efforts.”

Whereas the engagement with GPs and the implementation of various steps conceptualized in the GPOD framework has led to (and continues to do so) in positive movements in GPs, the journey is far from complete. Thus, the first emerging imperative is to sustain these positive movements and, at the same time, incorporating the learnings and recognizing the evolving needs and requirements of GPs.

A second emerging imperative is to scale the intervention in a manner that impacts the magnitude of the challenge substantially. That the current engagement across 25 pilot GPs is perhaps a tiny drop in the ocean needs no reiteration. To put it in perspective, Madhya Pradesh has close to 23,000 GPs whereas Jharkhand has 4,402. Yet, this pilot and the learnings it has afforded cannot be negated. Without this pilot, the application of the philosophy and principles of OD would have remained a mere theoretical exercise. Furthermore, the way forward would perhaps be fuzzy, at best. Thus, questions on how can the pilot, inclusive of its learnings, be scaled and who would be the stakeholders in this scaling process, assume significance. There are GPs in both the states that have moved to a stage where they are taking decisions and planning actions around larger deliverables that aim at systemic solutions.

There are GPs in both the states that have moved to a stage where they are taking decisions and planning actions around larger deliverables that aim at systemic solutions

There may be many ways of meeting these emerging imperatives; here are a few possibilities.

Imperative One: Sustaining and deepening the efforts of SPACE in pilot GPs.

- Sustaining ongoing practices and interventions: Several GPs within the pilot have reached a stage in bwhich they have collectively and collaboratively created aspirational visions for their GPs. Deriving from these visions, these GPs have identified tangible goals, which, in turn, require a deeper engagement. For instance, Rampur Mal has identified streamlining the provision of water, facilitating higher education and enhancing labour provision through MGNREGS. Towards this end, the GP has collectively made efforts to establish structures (mainly Standing Committees) and processes that will facilitate a deeper engagement. Committee members have been nominated and responsibilities have been assigned. Yet, it is critical to recognize that this is work in progress and, while gaining momentum, there is much that is yet to be done. For instance, delivering on specifics in any of these areas would require skills of collective bargaining and negotiation with higher tier PRIs, namely block and district panchayats, both of which play a critical role in delivering on these. Developing these skills requires hand-holding GPs. There are several internal and external challenges that GPs identify and acknowledge as intervention points as they move in this journey. PRADAN and Anode need to co-learn and co-create with GPs the ways and means of continual strengthening. In those GPs in which progress has been substantial, there is now an engagement around instituting processes to raise revenues through some of these committees.

- Transition Management: SPACE was initiated in year two of the election cycle in both the states. With the elections in the pilot GPs likely to happen in the end of 2019, effectively, the engagement with GP members would be for three years. What this also implies is that there will be a change in the elected representatives (and perhaps the functionaries too). The management of this transition is the first step to sustaining the change that is slowly taking form in the GPs. This can be effectively addressed by roping in aspiring candidates as well as past elected representatives in the change management process. Conversations that stand to ground the implications of the transition in the GP body on the momentum gained in affecting change in the day-to- day functioning of the GP will help bridge the gap likely to emerge with a new elected body. To quote an instance, in the pilot GPs in Madhya Pradesh, such conversations have led to an understanding that, probably, GPs will see a 50 per cent change in the elected representatives. Work on initiating the likely/aspiring people representatives into the GPOD framework is currently being planned with the GPs.

This visible movement of GPs towards debating and thinking collectively and working collaboratively, evidences the relevance of this framework in strengthening governance at the grass-roots.

This visible movement of GPs towards debating and thinking collectively and working collaboratively, evidences the relevance of this framework in strengthening governance at the grass-roots.

Imperative Two: Scaling the GPOD

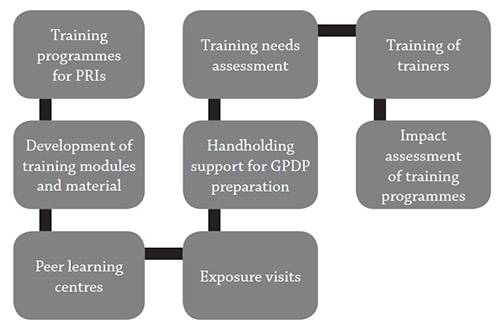

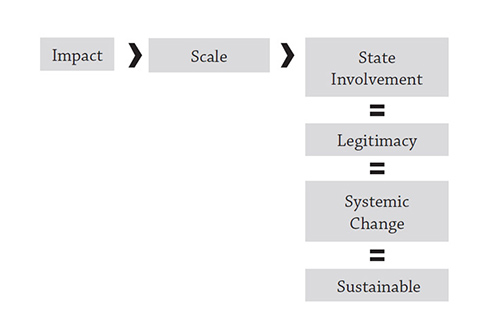

Scaling through state structures: Visible impact requires scale and the state departments are critical stakeholders in the scaling. Various state schemes and programmes that have a similar objective, that is, strengthening the GPs as units of autonomous units of local governance, can be leveraged and converged with. For instance, the Rashtriya Gram Swarak Abhiyan (RGSA) of the Government of India is premised on an acknowledgement of weak administrative and technical capacity at the GP level. It mandates capacity enhancement of PRIs to deliver on economic development and social justice within their respective jurisdictions. As per the guidelines, the PRIs must go through a foundational course that aims to cover the themes of “good governance, enhancing efficiency, transparency and participation.” Figure 1 outlines the specific activities that the scheme will cover.2

Figure 1: Training and Capacity Building: RGSA Guidelines

Figure 2: Visible Impact Requires Scale: Scale is Possible with the Involvement of the State

Furthermore, the guidelines recognize the potential of (and mandates) involving the existing scheme-specific committees (Joint Forest Management Committees, Village Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committee and Village Education Committee, to name a few) and community-based institutions (SHGs, CBOs) in strengthening GPs. A detailed reading of the guidelines points to an alignment of the aims and objectives of the GPOD framework with that of RGSA. It must be kept in mind that leveraging state structures, schemes and programmes helps mitigate the risk of creating parallel delivery mechanisms and structures while bringing in a degree of legitimacy and ensuring systemic change. Thus, scaling with the state departments and their programmes and projects is a possible way forward.

As in Karnataka, the GPOD framework in Madhya Pradesh and Jharkhand can be scaled to cover an entire block. There are two possible options of interventions at the block Level. The GPOD framework can be modularized as a training programme to be conducted through the State Institute of Rural Development through its infrastructure, while leveraging RGSA and its provisions. In doing so, the facilitation of GPs in the field cannot be done away with. It is recommended that this be operationalized through a host of identified organizations (such as PRADAN), which are engaged with GPs and have an established relationship with them.

- Scaling up through CSR: Scaling up can also be done through CSR involvement. Here, the state machinery of the zilla (district) panchayat could be approached with an intention to cover one block. Given the larger number of GPs, it may be prudent to have several CBOs hand-holding GPs in implementing the GPOD framework. Scaling up through CSR could also supplement scaling up through the State Institute of rural Development (SIRD).

Initiating change within GPs requires a clear understanding and acknowledgement that this institution is distinctly different from CBOs, the SHG being one of them

Initiating change within GPs requires a clear understanding and acknowledgement that this institution is distinctly different from CBOs, the SHG being one of them

Conclusion

M eeting both these imperatives requires pro-active thinking and strategizing. The following learnings from the field will assist in this strategizing:

- Initiating change within GPs requires a clear understanding and acknowledgement that this institution is distinctly different from CBOs, the SHG being one of them. Whereas strengthening citizenship (through SHG engagement) is necessary, it is not a sufficient condition to strengthen GPs. Instituting accountability mechanisms are a necessary condition and this can be achieved through an effective and meaningful engagement with elected representatives. Thus, the need for a balance between CBO-PRI engagements.

- Sustaining any change in this institution requires a degree of preparedness of a GP that is premised on complex dynamics, both at the individual and organization levels. Hence, the need for continuous and concerted engagement around, for\ instance, role realization by Ward Members, and increased understanding (of elected representatives as well as panchayat functionaries) of the statutory framework, mandated structures, processes and responsibilities, necessary to deliver.

- Initiating and sustaining change within the GP requires a necessary engagement with the larger eco-system comprising state departments and block and district panchayats, on the one hand, and CBOs on the other. In other words, it demands an intensity of engagement at various scales.

- Given this intensity of engagement, when scaling, those blocks/districts should be prioritized in which there is SHG saturation.4 This will have a two-fold advantage. On the one hand, it will provide functioning CBOs to enhance governance mechanisms. On the other, it will save energy and effort in mobilizing CBOs/ SHGs, thereby freeing up space for engagement with the GPs.

In conclusion, meeting the above emerging imperatives requires a two-fold engagement:

- designing and implementing a deeper engagement in the existing GPs in identified sectors, be it education, health, employment or agriculture;

- working with the state machinery and, or, leveraging CSR to intervene on scale. In doing so, it must be borne in mind that challenges and opportunities of scale are different from those of a deeper engagement. Yet, the experience with the latter, currently ongoing in GPs across the state, will inform the former.

Dr. Anjali Karol Mohan works with Anode Governance Lab as Lead, Research and Training. She is based in Bangalore.

3 There are geographies where SHG creation and mobilization (under the Government of India’s National Rural Livelihoods Mission) is complete.