Beyond Species Lists: What Participatory Tree Ranking Reveals About Forest Livelihoods

-Sattva Vasavada Sengupta, Executive, PRADAN

-Special Inputs from Ankit Tandon, Team Coordinator, PRADAN

What do forests mean when seen not through maps or species lists, but through the lives of those who depend on them? Drawing on participatory tree-ranking exercises with forest-dependent communities in Madhya Pradesh, this article explores how trees are valued differently across seasons, livelihoods, and gendered experiences revealing why local knowledge is essential for designing meaningful forest- and livelihood-based interventions.

Forests are often spoken about through maps, statistics, and species lists; measured in hectares, cover percentages, and biodiversity indices. Yet for communities who live alongside them, forests remain far more complex and, in many ways, mysterious. They are spaces of sustenance and uncertainty, abundance and loss, memory and change. What a forest offers is not fixed or uniform; it shifts across seasons, households, and generations. Much of this knowledge exists outside formal records, embedded instead in everyday practices of collection, observation, and use. Understanding forests, therefore, cannot rely solely on ecological inventories or external assessments. It requires engaging with the lived knowledge of those who walk these landscapes daily making visible the meanings, priorities, and relationships that remain otherwise unseen.

Historically, however, forests have rarely been understood on these terms. Knowledge about forests has largely been produced and interpreted by external actors like administrators, scientists, and development practitioners who approached them as resources to be mapped, regulated, and managed. In this process, communities were often positioned as respondents or beneficiaries, rather than as knowledge holders in their own right. Such approaches, shaped by colonial forestry practices, privileged technical expertise over lived experience, reducing complex forest–livelihood relationships to simplified categories and prescriptions.

Over time, the limitations of this approach have become increasingly evident. As forest-based livelihoods erode and access to non-timber forest products declines, it is clear that externally designed solutions alone are insufficient. Communities living in and around forests possess deep, experience-based knowledge of species, seasons, and trade-offs, knowledge that is essential for understanding both ecological change and livelihood vulnerability. Recognising this has necessitated a shift in how forests are studied and engaged with: from doing things for communities to working with them. It is within this shift that participatory methods assume critical importance, not as instruments of consultation, but as processes that centre communities as analysts of their own realities.

What are Participatory Methods?

Participatory methods are approaches to inquiry and planning that actively involve community members in defining problems, generating knowledge, and interpreting findings, rather than positioning them merely as respondents or beneficiaries. In rural development and natural resource management, these methods are especially significant because communities are embedded within the very contexts, interventions seek to address. They possess rich, experience-based knowledge that is often difficult to capture when programmes are designed externally. Beyond generating better information, participatory methods aim to redistribute decision-making power by creating spaces where communities and development organisations co-create knowledge. By recognising community members as co-analysts of their own realities, these methods ground interventions in lived practices rather than relying solely on the perspectives of development practitioners.

The Problem Statement

The relevance of participatory methods becomes particularly evident when they are applied to understand livelihoods that are deeply intertwined with local ecologies. This became especially clear during conversations and collective reflections with forest-dependent communities in four villages of Korka, Dharamshala, Matla, and Komo located in the Saletekri hills of Birsa block in Balaghat district, Madhya Pradesh. The region is characterised by extensive forest cover and a significant population of Baiga households, classified as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG), whose everyday survival remains closely linked to forest resources.

Despite the ecological richness suggested by official data, community discussions across these villages pointed to a shared concern: while forests continue to be central to everyday life, their ability to sustain livelihoods has been steadily eroding. According to the Indian State of Forest Report 2023, Madhya Pradesh has the highest forest cover by area in the country. Yet this statistical abundance contrasts sharply with lived experience. Community members frequently spoke of the gradual disappearance of forest produce that once formed the backbone of seasonal incomes, often articulating this change in similar terms:

“10 saal pehle bheja patta mil raha tha” (Ten years ago, Tendu Patta was abundantly available) “Aaj ke van mein kuchh nahi milta” (Today’s forests offer almost nothing)

Rather than being attributed to any single individual, these statements reflect a collective reading of change, an accumulation of everyday observations, comparisons with the past, and shared experiences of loss articulated across villages and social groups.

Mainstream development narratives and interventions often overlook forest-based livelihoods, treating them as marginal or supplementary. However, participatory conversations reveal that forests play a critical role in the annual expenditure cycles of tribal and forest-dwelling households. Income from Tendu Patta, for instance, often reduces the need to take on debt before the Kharif cropping season. Similarly, the sale of non-timber forest products such as Pihiri (bamboo mushrooms or Pleurotus), and Chirotta (Swertia chirayita) provides just enough cash flow to meet recurring market expenses throughout the year.

Anchored in PRADAN’s comprehensive livelihoods approach which views household income as a composite of multiple, interlinked sources, participatory methods have long been central to its work across thematic domains, including agriculture, water, and women’s institutions. These methods have consistently supported programme design by grounding interventions in community priorities and lived realities. Applying the same approach to forest-based livelihoods therefore emerged as a necessary extension. Given the substantial contribution of forests to household incomes, particularly during periods of vulnerability, forest-based livelihoods remained a critical yet under-explored domain that warranted closer and more systematic understanding through participatory inquiry.

Before conceptualising any project or intervention, it therefore became essential to engage more deeply with the forest itself—how it is used, valued, and perceived by those who depend on it. Based on proximity to forested areas, levels of dependence, and the need to unpack the dynamics of forest-based livelihoods, the villages mentioned above were selected for a participatory tree-ranking exercise.

Across these villages, participatory discussions were conducted primarily with Baiga men and women in three locations, while in Komo, a Gond (Scheduled Tribe)–dominated village, discussions were held with Gond women. This selection allowed for insights across different social groups and forest-use contexts, while remaining grounded in local realities.

Given that PRADAN’s presence in the Birsa block of Balaghat district is relatively recent (approximately 1.5 years), applying participatory methods in villages with lower levels of mobilisation posed distinct challenges—particularly in enabling meaningful participation from women. These uneven levels of mobilisation were clearly reflected in the composition and dynamics of group discussions.

As a male facilitator, it was observed that men from the community tended to position themselves closer and speak more readily, while women often sat at a distance and participated hesitantly, if at all. Incorporating the perspectives of those who speak less became challenging. Despite repeated efforts such as drawing attention to women, encouraging them to speak, and amplifying their responses, men frequently continued to dominate the discussions.

While this dynamic is uncomfortable, it underscores a critical limitation of participatory processes when they do not actively account for gendered power relations. If left unaddressed, discussions tend to privilege male perspectives, resulting in partial and gender-blind outcomes. This makes it essential for development professionals to consciously engage all sections of the community particularly women, whose voices are often unheard in development processes.

In this context, women’s perspectives were at risk of being overlooked, despite their distinct and equally valid priorities. For instance, when asked about important forest trees, men almost invariably identified timber-generating species (e.g., sal), whereas women emphasised non-timber forest produce (NTFPs) that contribute directly to weekly market incomes. Recognising and incorporating these gendered differences is therefore not only a matter of inclusion, but also critical for designing interventions that reflect the full spectrum of community needs.

Group sizes typically ranged from 7 to 15 participants. In villages with higher levels of mobilisation, discussions were conducted almost entirely with women from Self-Help Groups (SHGs). In contrast, villages with lower mobilisation saw mixed groups, usually comprising three to four women and men each, most of whom were SHG members. Creating a space where all participants could engage without hesitation required active facilitation, periodically inviting quieter voices, returning to those who had not spoken, and acknowledging differing viewpoints.

Although women’s participation was initially limited in some settings, sustained engagement made a noticeable difference. Repeatedly inviting women into the conversation and creating opportunities for them to respond gradually increased their confidence, enabling more spontaneous and independent participation over time.

The Importance of Forest Based Livelihoods

Photo: Meeting of women community members of Komo Village to discuss the importance of trees and seedballs

While the contribution of forests to livelihoods has been discussed briefly, forests occupy a far more expansive role in the everyday lives of forest-dependent communities. To understand why participatory ranking was necessary, it is important to unpack these multiple, overlapping roles and examine the broader significance of forests within these contexts.

Trees and forests play multiple, overlapping roles in rural livelihoods, extending far beyond their ecological significance. For tribal households living in close proximity to forests, they form a critical source of income through the collection and sale of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) such as fruits, seeds, leaves, and medicinal materials. Seasonal forest products like mushrooms during the monsoon, Chirotta (Swertia chirayita) in winter, and Tendu Patta (Diospyros melanoxylon) and Mahua (Madhuca longifolia) in summer provide essential supplementary income across the year.

Mushrooms, locally known as Pihri, are typically sold for ₹100–150 per basket. On average, one person can collect about one basket per day, generating modest but reliable income that helps meet essential weekly household expenses.

During winter, dried Chirotta plants are collected and spread on village roads for threshing. In the absence of mechanised processing facilities, passing vehicles are used to separate the seeds, which are then collected and sold at approximately ₹20 per kilogram. This practice reflects the community’s adaptive and resource-efficient processing methods under constrained conditions. A single day of collection can yield 3–5 kg of seeds, and the resulting income often supports household purchases at the weekly market.

Dried Mahua serves multiple purposes. It is primarily used for distillation to produce alcohol for social functions and is generally not sold. Sometimes, it also functions as a form of household cash reserve, liquidated when immediate needs arise. While daily market purchases are often financed through the sale of millets such as kodo, dried Mahua is occasionally sold to cover small expenses (typically less than ₹100–200).

Tendu Patta collection is used in making beedis, a widely consumed and indigenous form of cigarettes. On average, an individual can collect 100–200 pudas or gaddis (bundles of 50 leaves each), depending on availability and individual efficiency. The compensation rate is ₹400 for every 100 pudas/gaddis collected.

Based on a survey of 30 households in a Baiga (PVTG) hamlet, the average income earned from Tendu Patta collection was ₹5,760/year per household. This income is directly transferred to bank accounts and typically released just before the onset of the kharif season. Such timely cash inflows are critical, as they reduce households’ dependence on loans for kharif cultivation.

Beyond income, NTFPs play an important role in food and nutrition security. Seasonal fruits, edible leaves, and supplementary foods become especially significant during lean summer months, when agricultural activity is minimal and market dependence increases. Forest produce collected in winter and stored or dried helps bridge these gaps. Mahua fruits and seeds, for instance, are used to produce oil during periods of low income and resource availability, reducing reliance on purchased goods. Fruit-bearing trees such as mango (Mangifera indica), bihi (Psidium guajava), and avla (Phyllanthus emblica) are valued not only for their taste but also for their nutritional contribution during these lean periods.

Trees also serve as a primary source of fuelwood for cooking and heating, with different species valued for their burning properties, some producing quick heat, others offering a longer, slower burn. Certain species are preferred as fodder, particularly during dry seasons when grazing options are limited. Livestock, too, have preferences; goats readily feed on Dubi* leaves, while ignoring other species.

For these reasons, the value of trees is neither uniform nor constant across the year. Fruit-bearing species may be prioritised during summer for consumption and sale, fuelwood species during monsoon or winter, and fodder species during periods of scarcity. These shifting priorities underscore the need for methods that can capture variation across seasons, uses, and social groups.

Participatory ranking helps bring out these differences by allowing community members to explain what matters to them and why, instead of forcing all trees into a single definition of “importance.” When done well, the exercise becomes less about assigning ranks and more about conversation where people discuss, disagree, and reflect together. The focus shifts from the final list to the reasons behind it, using local terms and examples, and creating space for quieter participants to speak. In doing so, decision-making moves away from fixed species lists towards priorities shaped by local needs and experiences, making forest- and livelihood-based interventions more relevant and sustainable.

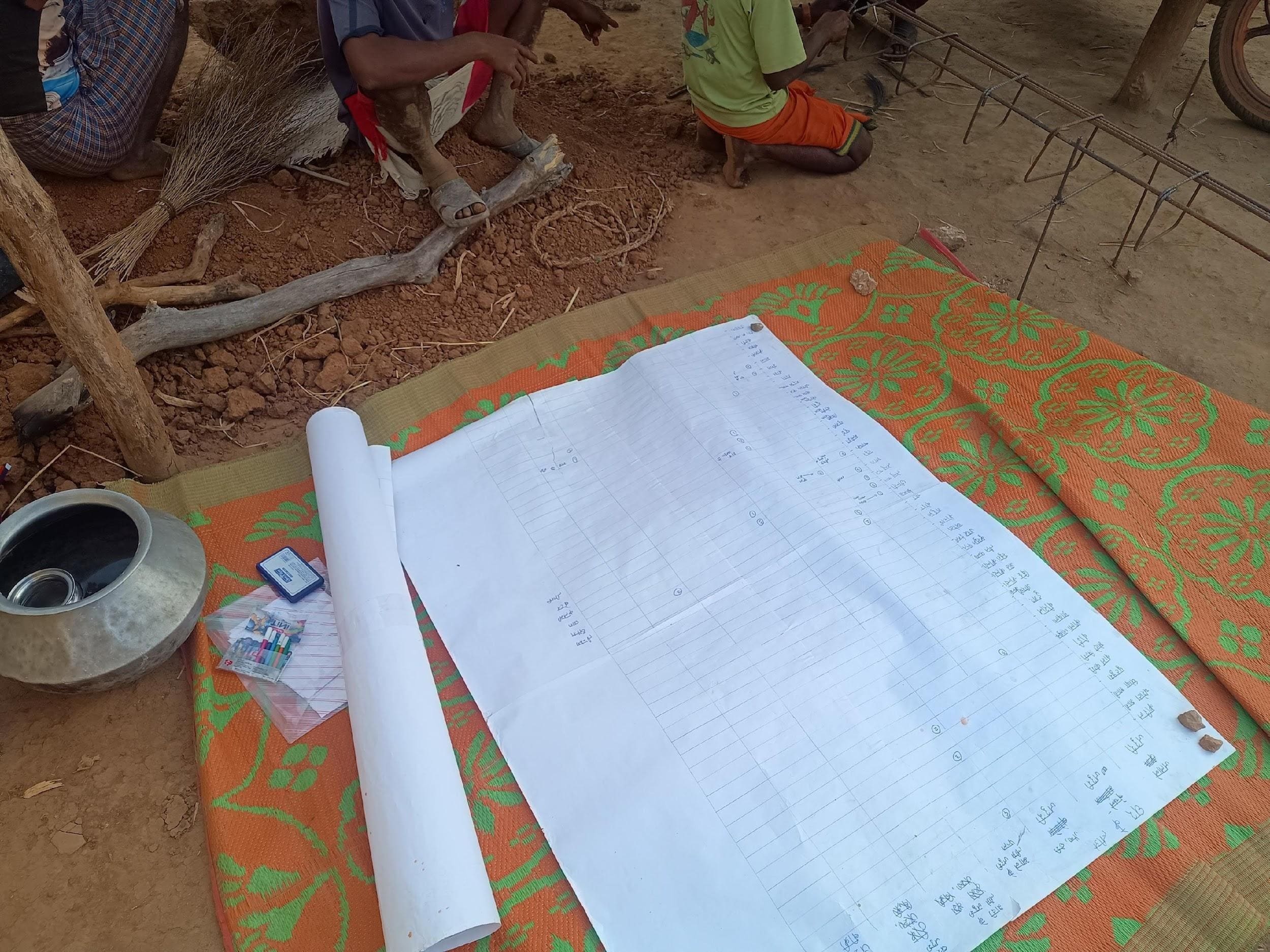

Photo: A seasonal map and ranking of all NTFP available in an ultra poor Baiga hamlet in Macchurda

From Listing to Ranking: Applying Participatory Methods in Practice (Field Process and Methodology)

Before initiating any exercise that asked participants to rank trees by importance, it was essential to first establish a comprehensive list of tree species and forest produce that people derive value from. This preliminary step ensured that subsequent ranking exercises were grounded in local knowledge and did not exclude species that may otherwise be overlooked.

An initial listing exercise was conducted in Komo village with eight participants (six women and two men) and two facilitators. In the initial meetings, facilitation was jointly undertaken by the author (Sattva Vasavada Sengupta) and Ankit Tandon, the team coordinator of the team in which the author was placed and also the author’s field guide, as part of the Development Apprenticeship programme. Subsequently, the author led the remaining discussions independently as part of his apprenticeship assignment.

Women played a central role in identifying valuable trees and non-timber forest products (NTFPs). The discussions were organised seasonally—monsoon, winter, and summer which helped surface a wide range of forest resources and highlighted how their value shifts across the year. Embedded within the listing process were detailed discussions on use cases, histories, and changing availability, enabling a richer understanding of how different species contribute to livelihoods.

For instance, when Karudara was identified as a forest product, it was simultaneously recorded on chart paper while discussions unfolded around its uses and recent relevance. Women shared that Karudara has gained importance in recent years as a local treatment for malaria, prepared by boiling the plant in water. Participants also mentioned that it is occasionally purchased by itinerant vendors who visit the village in pickup trucks, reportedly at around ₹15 per kilogram. While community members were unsure of the end use, they speculated that it may be procured for medicinal purposes. One facilitator focused on documentation while the other guided discussion, enabling rapid listing alongside collective learning.

Once a consolidated list of tree species was generated in Komo, one SHG meeting was scheduled in each of the four villages to conduct participatory tree-ranking exercises. Discussions were held separately within villages, given the distances between them. In villages with lower mobilisation, such as Korka and Dharamshala, initiating conversation proved challenging. Participants were initially uncertain about the purpose of the exercise and sought to understand the identity of the facilitators, with some asking whether they were associated with the Forest Department. This hesitation reflected a broader distrust of external actors, a sentiment particularly pronounced in tribal and PVTG habitations.

Language further complicated participation, particularly during discussions with Baiga women. While facilitators attempted to use local terminology and broken Chhattisgarhi, communication gaps remained. Not all information could be fully understood, and repeated clarifications risked disrupting the flow of discussion. Despite these limitations, sustained engagement allowed facilitators to grasp a substantial portion of the conversations. As in much field-based participatory work, the process involved balancing methodological intent with practical constraints; listening carefully, probing where possible, and acknowledging what could not be fully captured.

As discussions unfolded, participants reflected on their evolving relationship with forests. Many recalled a time when forests provided nearly everything households required, contrasting sharply with the present, where both diversity and availability have declined. Access has further worsened due to invasive species such as Lantana (Lantana camara) , which make forest traversal difficult. The shrubs of the Lantana make it almost impossible to pass through. They have thorns that make it even harder to go near them. These reflections naturally led into discussions on income loss, reduced access to NTFPs, and increased physical effort required for collection providing a contextual foundation for subsequent ranking exercises.

Gradually, facilitators introduced the idea of documenting priorities visually. While initial apprehension remained rooted in past experiences of exploitation by bahar wale (outsiders), PRADAN’s presence in the region over the past 1.5 years helped build trust. References to earlier engagements particularly the installation of a 10 HP solar lift irrigation system in a nearby village played a key role in this process. The intervention enabled consistent and reliable irrigation, allowing women and men farmers to irrigate their fields beyond the kharif season and undertake rabi cultivation. These visible and sustained benefits circulated quickly across villages, helping participants recognise the facilitators as familiar and trustworthy actors.

Rankings were conducted using written names of tree species rather than physical markers such as twigs or leaves largely due to the impracticality of sourcing materials for over fifty species. Participants collectively identified the most important species within each category, assigning ranks sequentially. Facilitators assisted with documentation, ensuring that participants retained control over decision-making while receiving logistical and documentation support.

Conducting ranking exercises across multiple villages allowed priorities to reflect village-specific realities. For example, while some villages reported adequate access to Tendu Patta, participants from Dharamshala village noted significantly lower availability compared to neighbouring settlements.

Through the initial listing process, four broad categories of tree use emerged organically: species valued primarily for sale, for household consumption, for fuelwood, and for livestock. These categories were not imposed externally but arose from participants’ own descriptions of how trees feature in daily life. Within each category, species were collectively ranked based on perceived importance. Frequency counts were used to observe how often particular species appeared across village discussions, offering a comparative though not statistically representative sense of priority. To ensure these insights held beyond the initial discussions, a small follow-up exercise was carried out with other community members.

AGGREGATING PARTICIPATORY RANKINGS

While rankings were generated at the village level, aggregating these rankings across villages posed methodological challenges. Village-specific priorities meant that simple averaging of ranks risked obscuring meaningful differences. This becomes clear through a simple example:

| Komo | Name of Fuelwood Tree | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Saja(Terminalia tomentosa) | 1 | |

| Dhauda(Anogeissus latifolia) | 2 |

| Ranjana | Name of Fuelwood Tree | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Dhauda (Anogeissus latifolia) | 1 | |

| Saja (Terminalia tomentosa) | 2 |

In Komo village, Saja was ranked as the most important fuelwood species, followed by Dhauda. In contrast, in Ranjana village, Dhauda was ranked first, with Saja second. If ranks were averaged across the two villages, both species would receive an identical average rank of 1.5, despite their differing levels of importance within each village. Such an approach would flatten local distinctions rather than reflect them.

To address this, rankings were aggregated using a frequency-based approach rather than numerical averages. First, within each village, groups identified and ranked only their most important species within each category (for example, fuelwood). Second, across villages, species were prioritised based on how frequently they appeared among the top-ranked lists. Thus, if a species such as Saja was identified as important in all four villages, it was ranked higher in the aggregate results than a species like Dhauda, which may have appeared in only two villages.

This approach allowed the aggregated rankings to reflect shared priorities across villages while preserving local variation. Rather than producing a misleading “average” importance, frequency-based aggregation captured the relative prominence of species across different contexts in a way that remained true to the participatory intent of the exercise.

Key Findings Across Use Categories

The participatory ranking exercises revealed distinct patterns in how communities value trees and NTFP across different use categories. Rather than a single hierarchy of importance, the results highlight multiple, overlapping value systems shaped by livelihood needs, seasonality, and access.

Trees and NTFPs valued for sale

| Species | Frequency of Mention (Higher frequency = higher priority) |

|---|---|

| Harra (Terminalia chebula) | 4 |

| Avla (Phyllanthus emblica) | 3 |

| Char (Buchanania cochinchinensis) | 3 |

| Mahua (Madhuca longifolia) | 3 |

| Bhelva (Semecarpus anacardium) | 2 |

| Tendu (Diospyros melanoxylon) | 2 |

| Kusum (Schleichera oleosa) | 1 |

| Pihri (Pleurotus) | 1 |

While species such as Harra, Avla, and Char emerged as high-priority commercial NTFPs, participants noted a significant decline in their availability. This decline was attributed largely to deforestation and extractive harvesting practices. Harra, in particular, grows on tall trees, making fruit collection difficult. As a result, instead of climbing trees, people often cut them down to access fruits, a practice that has sharply reduced the availability of these species over time.

In contrast, Tendu and Pihri were reported to have declined as well, but continue to be sold in relatively higher volumes due to easier access and established market demand.

Trees and NTFPs valued for own consumption

| Species | Frequency of Mention (Higher frequency = higher priority) |

|---|---|

| Aam (Mango - Mangifera indica) | 3 |

| Bihi (Guvava - Psidium guajava) | 3 |

| Avla (Phyllanthus emblica) | 1 |

| Char (Buchanania cochinchinensis) | 1 |

| Chindi* | 1 |

| Jamun (Syzygium cumini) | 1 |

| Pihri (Pleurotus) | 1 |

Trees valued for household consumption were primarily fruit-bearing species that supplement diets during lean periods. These species were valued not only for nutrition but also for taste and cultural familiarity. Unlike commercially prioritised NTFPs, consumption-oriented species were often discussed in terms of reliability and household needs rather than income potential.

Trees valued for fuelwood

| Species | Frequency of Mention (Higher frequency = higher priority) |

|---|---|

| Saja (Terminalia elliptica) | 4 |

| Dhauda (Anogeissus latifolia) | 3 |

| Senha (Senna siamea) | 3 |

| Kalmi (Mitragyna parvifolia) | 2 |

| Bhelva (Semecarpus anacardium) | 2 |

| Avla (Phyllanthus emblica) | 1 |

| Boer (Schotia brachypetala) | 1 |

| Gothiya* | 1 |

| Kauha* | 1 |

| Khirsadi* | 1 |

Two key criteria emerged consistently in fuelwood rankings: the amount of smoke produced and the duration of burning. Species that generated less smoke and provided a longer, steadier burn were prioritised, reflecting practical considerations related to cooking comfort, health, and fuel efficiency.

Trees valued for livestock

| Species | Frequency of Mention (Higher frequency = higher priority) |

|---|---|

| Boer (Schotia brachypetala) | 4 |

| Dubi* | 2 |

| Dumar* | 1 |

| Ghari* | 1 |

| Gothiya* | 2 |

Livestock-related preferences were shaped by fodder availability and animal behaviour. Participants frequently noted that livestock, particularly goats, exhibit strong preferences for certain species, influencing which trees are protected or valued during periods of fodder scarcity.

Interpreting the Results

The participatory tree-ranking exercises underscore the multifunctional role of trees in rural livelihoods. Species valued for commercial sale coexist with those critical for food security, fuelwood, and livestock, and priorities vary across use categories rather than converging into a single list of “important” trees. Community preferences cut across economic, nutritional, and ecological considerations, highlighting the limitations of uniform species promotion.

Based on collective rankings across villages, a set of priority species was identified for each use category. These results provide a grounded basis for designing forest- and livelihood-based interventions that are responsive to local realities, seasonal needs, and sustainability concerns rather than relying on externally defined or prescriptive species lists.

| For Sale | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Harra ((Terminalia chebula) | 4 |

| Avla (Phyllanthus emblica) | 3 |

| Char (Buchanania cochinchinensis) | 3 |

| Mahua (Madhuca longifolia) | 3 |

| For Own Consumption | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Aam (Mangifera indica) | 3 |

| Bihi (Psidium guajava) | 3 |

| Livestock | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Boer (Schotia brachypetala) | 4 |

| Dubi/Dumar* | 3 |

| Fuel Wood | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Saja (Terminalia tomentosa) | 4 |

| Dhauda (Anogeissus latifolia) | 3 |

| Senha (Senna siamea) | 3 |

Discussion and Implications: Learning from Participation and Personal Reflections

This exercise offered a rare window into a knowledge system that remains largely absent from mainstream development discourse. While agriculture, climate, and livelihoods are widely discussed in policy and practice, forest-based knowledge, particularly as held by tribal and forest-dwelling communities, is often invisible outside these ecosystems. Engaging directly with communities revealed not only what trees matter, but why they matter, when they matter, and to whom, insights that cannot be derived from secondary data or externally designed frameworks.

Methodologically, the participatory ranking exercises reaffirmed the strength of participatory methods as tools for grounded inquiry rather than mere data collection. Beyond producing ranked lists or frequency counts, the process generated dialogue, surfaced local rationales, and allowed priorities to emerge organically through discussion and disagreement. The emphasis on reasoning over scores ensured that rankings reflected lived realities rather than abstract notions of value. Importantly, participation was not uniform or frictionless; it required active facilitation, patience, and adaptation to language, literacy, trust, and gendered power dynamics. These challenges were not limitations of the method but reminders that participation is a process, not a technique.

The findings also have clear implications for programme design and policy. The results demonstrate that trees cannot be treated as homogenous assets or promoted through uniform species lists. Commercially valuable NTFPs coexist with species critical for food security, fuelwood, and livestock, and their importance shifts across seasons and contexts. Participatory scoping exercises such as tree listing and ranking can help ensure that forest-based interventions, whether related to plantation planning, NTFP promotion, or restoration are context-specific, socially grounded, and ecologically sustainable.

Looking ahead, the ranked species lists generated through this exercise can inform future initiatives, including plantation planning, seed ball interventions, and targeted NTFP promotion, depending on community priorities and ecological feasibility. More broadly, the experience highlights the necessity of conducting rapid, participatory scoping exercises whenever entering new regions. Even within the same district, micro-variations in forest access, species availability, and livelihood dependence are significant. Recognising and responding to these variations is essential if interventions are to remain relevant and effective.

Ultimately, this exercise reinforces a core insight of participatory practice: communities are not just sources of information, but analysts of their own realities. When given the space to reflect, debate, and prioritise, they generate knowledge that is both rigorous and deeply rooted in lived experience, knowledge that should inform not only projects on the ground, but also how forest-based livelihoods are understood and supported in policy and practice.

*Note: Local tree names have been retained where scientific identification was not possible or where multiple species share the same local name across regions.

About the Author