Beyond Survival: Farming for the Future

Jibdas Sahu, Team Coordinator, PRADAN

Special inputs: Anshika Singh, Executive, PRADAN

Introduction

For decades, I’ve seen the fields of rural India weather the challenges of rugged terrain, erratic rainfall, and shrinking landholdings. Agriculture, the backbone of life here, often felt less like a path to prosperity and more like a test of survival. In regions with hilly, undulating terrain—interspersed with forest patches—nearly 70% of rainfall escapes as surface run-off, leaving the land dry soon after the monsoon. With most households dependent on rain-fed farming, sustaining livelihoods becomes increasingly difficult without reliable water sources.

Yet, I have also witnessed change unfolding. Across villages where I’ve worked, communities in collaboration with stakeholders like Gram Panchayats, government institutions, and us at PRADAN, have been driving transformation rooted in innovation, resilience, and collective learning. Bringing innovation to rural India’s fields has long been at the heart of PRADAN work. Since its inception in 1983, PRADAN has developed transformative models tailored to small and marginal farmers—ranging from Tasar and poultry farming to Integrated Natural Resource Management (INRM), lift-irrigation, and solar-powered irrigation. These weren’t just technical fixes—they evolved through field trials, farmer feedback, and partnerships that unlocked the potential of neglected landscapes.

Take lift irrigation, for instance. It has transformed previously fallow highland patches in Jharkhand. These slightly sloping lands, where water could not stagnate, were once left uncultivated due to erratic rainfall and lack of irrigation—despite being ideal for growing vegetables, fruits, pulses, and oilseeds. With the shift to solar-powered lift irrigation over time, I saw farmers gain access to sustainable, reliable, and low-cost water sources. This encouraged them to invest in better seeds, compost, and timely farming practices. Crops were sown earlier, harvests more secure, and incomes increased. Villages like Kanhaidih, Mohanpur, and Jangla in Kathikund block of Dumka district of Jharkhand now showcase thriving farms where mustard and paddy flourish on land once left barren. In Jangla, a single solar unit supports mustard cultivation across 25 acres—even during dry years, as a second crop during Rabi season (after assured paddy cultivation during Kharif season).

Tasar farming, once uncertain and scattered, has become a structured value chain. We worked with rearers, the Central Silk Board (commonly known as CSB), and local institutions to ensure doorstep delivery of Disease-Free Layings (DFLs), expand host plantations, and build village-level samitis and regional and district level cooperatives. Local women now add value through reeling and spinning at Common Facility Centres, supplying weaving centres. In Dhaka–Dhighapahari, two adjoining villages in Dumka district of Jharkhand, 135 farmers across 116 hectares now earn around ₹40 lakh annually from Tasar.

In poultry, too, I’ve seen women earn ₹15,000–₹35,000 per year by rearing up to 500 birds per batch, across 4–5 cycles annually. Our supported cooperatives handle input supply, medication, and marketing, while rearers manage daily care. These enterprises have brought steady income into the hands of women, backed by infrastructure grants, working capital, and strong local institutions.

From reviving barren land to building resilient rural enterprises, our interventions are redefining what’s possible. What began as small experiments are now being adopted in broader developmental systems—gaining momentum among governments, civil society organisations, and rural enterprises alike.

A Testament to Change

Being born into a farmer’s family and later choosing a career that combined agricultural work with education laid the foundation for my deep understanding of farming. It allowed me to view agriculture not just as an occupation but as a system deeply connected to social dynamics of caste, gender, accessibility, etc. —and it sparked a lifelong curiosity and commitment to improving the lives of farmers.

In 1995, soon after completing my Master’s in Agriculture, I joined PRADAN. Since then, I have been working in remote districts of Bihar and Jharkhand, primarily with tribal communities and other marginalized groups. Over nearly three decades, I have witnessed a transforming landscape—shaped by both persistent challenges and remarkable resilience.

In the undulating terrains of Agro-Climatic Zone VII, where slopes range between 3% to 7%, irrigation is scarce, water resources are limited, and the climate varies from dry to semi-humid with a distinct monsoon, the agricultural potential remains largely untapped. In such a context, the efficient use of available resources isn't just important—it’s essential. Most families here have around five members—typically a couple, their two children, and an elderly parent. As sons grow older and start their own families, they are often allocated a portion of the land and some initial support to establish separate households, often within the same compound. Over generations, this practice has led to the steady fragmentation of landholdings.

Small and marginal farmers—many of them women—now cultivate less than a hectare of land, which is far too little for traditional farming to ensure a sustainable income. With limited options for other viable livelihood opportunities, agriculture remains the backbone of rural life. As landholdings continue to shrink with each generation, the challenge is no longer just about cultivation—but about making the most of every available patch of land to meet both the food and economic needs of the family. Despite the presence of natural resources like land and forests, agriculture often fails to meet everyday cash needs. As a result, many men migrate in search of work, leaving women to shoulder the responsibility of farming and managing the household. But when agriculture is reimagined—not merely as cultivation, but as a system that integrates land, water, and market access—transformation becomes possible. It opens the door to better yields, diversified income sources, and a more resilient way of life.

Women farmers in these regions are moving beyond subsistence—reimagining agriculture as a diversified, income-generating system that meets both present-day needs and future aspirations. With shrinking landholdings and limited irrigation, market access, and technology, their pursuit of better livelihoods has driven innovation from the ground up.

Across villages, women have adopted models like smallholder poultry, where a 500–1000 bird shed owned by each woman member can generate ₹35,000 annually. But this wasn’t always the case. Earlier, backyard poultry was largely need-based, practiced without any institutional structure. Birds were reared informally, with limited access to quality inputs, veterinary care, or markets—making it an unreliable source of income. Today, women manage daily operations with care, while women-led cooperatives ensure economies of scale in input procurement, veterinary support, and market linkages, transforming poultry into a steady and viable livelihood option.

In parallel, Producer Groups offer a synchronized crop production system—like watermelon, vegetables, and mustard—within agricultural production clusters*. By staggering seedling supply and coordinating planting schedules, farmers avoid market intermediaries and earn ₹10,000–₹25,000 per season. Nodal Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) play a key role in market coordination and continuity. FPOs play a crucial role in building farmers' collective bargaining power, improve market access, and ensure fair pricing—enabling smallholders to operate at scale and with greater confidence.

Some are even adopting multi-tier farming systems—combining vegetables, fruits, timber, and even integrating small livestock at the periphery of farmland or in adjacent spaces—to ensure year-round income, long-term returns, and improved nutrition. While livestock may not form the vertical layering of traditional multi-tier farming, their integration into the overall farming system reflects a holistic approach suited to the unique needs of sparsely populated, tribal-dominated villages in rural India. These grassroots innovations aren’t isolated efforts; they are shaping a new agricultural vision rooted in local realities.

Photo: Multi-tier farming

What succeeds in one village inspires another. Setbacks refine strategies. Through shared knowledge and continuous adaptation, solutions evolve—not as temporary fixes, but as long-term shifts in how agriculture is practiced.

Collaboration for Change!

Despite the state’s abundant forests, rivers, natural resources, and human potential—and the growing emphasis on innovation in agriculture and collective growth—I have seen how Jharkhand continues to have one of the highest concentrations of rural socio-economic marginalisation in South Asia. According to NITI Aayog’s 2023 Multidimensional Poverty Index, 28.81% of our population falls below the poverty line, ranking us 27th among 28 Indian states (https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2023-08/India-National-Multidimentional-Poverty-Index-2023.pdf). In Bihar, districts like Banka, Jamui, and Nawada—where I have also worked—struggle with some of the lowest per capita incomes in the country—between INR 22,000 and 30,000—amid widespread malnutrition and deep-rooted gender inequality.

Government initiatives like the Bihar Rural Livelihoods Promotion Society (JEEViKA) and the Jharkhand State Livelihoods Promotion Society (JSLPS), along with our ongoing interventions at PRADAN, have made strides in expanding economic opportunities in rural areas. However, I continue to see that many women still lack control over their own livelihoods. While they continue to work tirelessly in the fields, key decisions are often made by male members of the household.

Women’s participation in Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) remains limited, and they are frequently excluded from critical market-linked services—such as access to quality seedlings, seeds, bio-cultures, bio-pesticides, or doorstep procurement of their produce at fair prices. Although mobility has improved over the years, meaningful access to financial resources and markets is still far from equal.

Like many stories I’ve come across in the villages of Bihar and Jharkhand, my experience with Karmantanr, a village deep within Gopikandar Block of Dumka district in Jharkhand, is almost the same.

Photo: A typical hamlet in the village of Karmantanr

The Path to Transformation

Beneath the rugged beauty of Gopikandar block, I’ve come to witness a silent crisis. Torrential rains erode the soil. Water disappears before it can nourish. Agriculture, the region’s lifeline, remains stunted.

For families I am in touch with, who survive on shrinking landholdings—averaging just 0.68 hectares—farming is more than a means to earn; it’s a constant negotiation with uncertainty. First-generation farmers, many of them women, battle against low yields, inaccessible irrigation facilities, and unreliable market access, trapped in a cycle of economic insecurity.

Still, amid these everyday hardships, I see signs of transformation beginning to emerge.

With steady support for better technology, local businesses, and market-focused solutions, farming here is no longer just about survival. Through rural enterprises and partnerships, I’ve seen new opportunities opening up. Institutions like ICAR-RCER are working closely with farmers to turn once-barren fields into productive, thriving farmland.

When communities are empowered with the right tools and knowledge, I believe transformation is inevitable. Livelihoods strengthen. Confidence grows. And the land, once burdened by scarcity, begins to sustain those who depend on it—offering not just food, but hope for generations to come.

Recognizing this need, we at PRADAN, in partnership with Axis Bank Foundation, launched a four-year project in July 2024 titled “Providing Livelihood Support to 73,000 Households in Jharkhand and Bihar.” This initiative aims to strengthen women-led institutions, promote farm and non-farm enterprises, and enhance land and water management—paving the way for more resilient rural livelihoods. We are building on insights from earlier initiatives such as the APPI-CLAP (Azim Premji Philanthropic Initiative-Comprehensive Livelihoods Adaptation Pathways) project (2020–2023), which focused on regenerative agriculture, nutrition-sensitive cropping, gender inclusion, and livelihood models for ultra-poor families, as well as linking them to social security schemes. Other relevant experiences we are drawing from include the HDFC-FRDP (Focused Rural Development Project) project (2021–2024), which emphasized FPO promotion, livestock and agriculture development, and nursery-based seedling systems; and our Solar Lift Irrigation initiative supported by Bank of America in 2018–2019, which demonstrated scalable models for sustainable irrigation.

Photo: A training session organized under the Axis Bank Foundation-supported project. (Representational image; similar trainings were conducted in Karmatanr village, Dumka district, Jharkhand)

Turning Vision into Impact

The project’s interventions are designed to create lasting change by improving access to resources, strengthening rural economies, and ensuring that women take the lead in shaping their own futures. These efforts translate into measurable outcomes:

- Reviving Land and Water for Livelihoods We are working to restore over 10,000 hectares of land using regenerative practices to improve soil health, check erosion, and ensure irrigation for nearly 80 families. Natural resource management plans are underway in 500 villages across 150 Gram Panchayats, supported by us at PRADAN and the Department of Panchayati Raj. To boost water access and livelihood assets, we have mobilized ₹125 crore from various government programs like Agri Smart Village, Jharkhand State Millets Mission, and others to enhance water access and build livelihood assets such as seed banks, processing units, and cold chains.

- Scaling Livelihoods through the Agricultural Production Cluster (APC) Approach* Over 35,000 households are part of the APC model, earning ₹2 lakh or more annually through farm, allied, and off-farm activities. Around 500 rural entrepreneurs and 1,000 girls in Bihar are being supported through skill-building and enterprise development, while 22 women-led FPOs are channeling sustainable incomes directly to women. So far, ₹30 crore has been mobilized as working capital from banks and other financial institutions to fuel these rural ventures.

- Reaching the Most Vulnerable 3,000 ultra-poor households—often excluded from mainstream development—are now supported through targeted safety nets and livelihood interventions, ensuring a minimum annual income of ₹30,000. These include women-headed, elderly, or disabled families with little access to credit, skills, or social support, who are often overlooked even within their own communities.

By ensuring access to resources, financial support, and sustainable livelihoods, the project fostering a shift from subsistence to self-reliance.

A New Dawn in Karmatanr: In collaboration with the project

Under the project, on October 30, 2024, we at PRADAN signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with ICAR-RCER under the initiative "Providing Livelihood Support to 73,000 Households in Jharkhand and Bihar." ICAR-RCER had previously developed the Multi-Tier Cropping System for Rainfed Uplands of Eastern India (ICAR-NRM-RCER-Technology-2023-028)—a model that integrates fruit crops and timber trees with paddy and finger millet.

Photo: Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with ICAR-RCER

On a crisp morning in February 2025 in Karmatanr, I stood with farmers who had gathered around a two-acre plot—land that held the promise of transformation. They had endured seasons of uncertainty, of drought-stricken crops and meager harvests. But today was different.

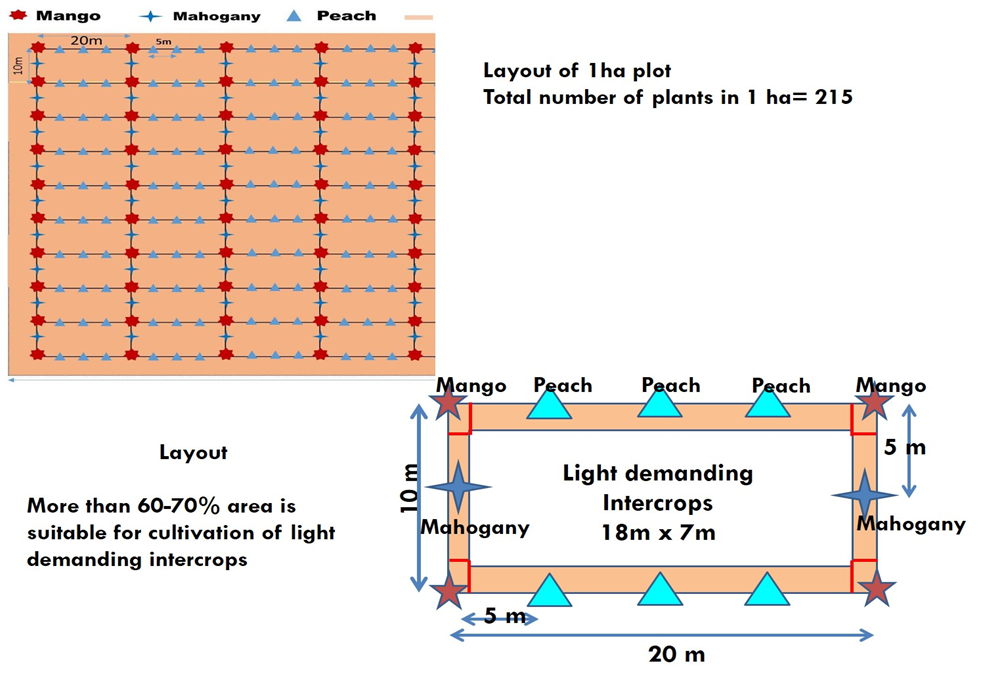

Our team from PRADAN, alongside scientists from ICAR-RCER’s Palandu Unit and with support from the Axis Bank Foundation, had arrived to demonstrate the Multi-Tier Farming model for rainfed areas—an approach designed to utilize land to its maximum efficiency by combining horizontal and vertical space. Unlike conventional orchards where dense fruit tree spacing eventually shades out field crops, this model strategically uses trees of varying heights—like Mahogany, Mango, and Guava—planted with wider spacing and directional pruning to ensure adequate light reaches the ground. This allows for the continued cultivation of light-demanding crops like paddy, millets, mustard, and vegetables, making it ideal for mixed cropping in both rainfed and irrigated conditions.

Photo: Field work being done for multi-tier farming

This wasn’t just an experiment; it was a carefully designed intervention tailored to Karmatanr’s undulated terrain and climate realities. Located in Agro-Climatic Zone VII—the Eastern Plateau and Hill Region—Karmatanr experiences a dry to semi-humid climate, marked by a distinct monsoon with high rainfall variability, shallow and acidic soils, and sloping lands with poor water retention. Irrigation facilities are sparse, and most farming here is rain-dependent, making traditional mono-cropping highly vulnerable to climatic fluctuations. In such a challenging setting, maximizing land use through multi-tier systems offers not just efficiency, but better economic prospects.

This system has proven to generate an annual income of ₹50,000–₹60,000 per acre and has shown success in some parts of Eastern India. We at PRADAN are piloting this model for the first time. In collaboration with ICAR-RCER, we are working to adapt the approach to suit the specific agro-ecological and socio-economic conditions of small and marginal farmers in the region—making this a significant step into new terrain.

Among the farmers watching closely were Suhasini Hansda and her spouse, Lukas Hembrom—two individuals who dared to dream of a different future for their village. "Agar hum iss zameen ko sahi se istemal karenge, toh humein achhe nateeze mil sakte hain" (If we use this land wisely, it will give back to us), said Suhasini as she observed the layout taking shape.

Photo: Suhasini Hansda and her spouse, Lukas Hembrom working in their field

In that moment, I saw not just a farmer, but a woman quietly carrying the weight of possibility—for her land, her family, and her village. Hope, here, does not shout. It simply keeps showing up, season after season.

I left inspired and deeply moved—by her conviction, by the promise of the land, and by a renewed resolve to contribute toward the efficient use of Karmatanr’s agricultural potential.

The model, customized for Karmatanr’s unique conditions, stacked different tiers of vegetation—mahogany trees providing less shade but quick vertical growth (till 15 ft to 20 ft, no branches allowed), grafted mangoes placed in the corners of the micro plot, and guavas lined along the mangoes at the mid-tier. A variety of vegetables flourished at ground level under controlled irrigation. But this wasn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. It evolved, shaped by the lived experiences of farmers and the nuances of their land.

Innovating for Karmatanr’s Future

In place of millets—which are nutritionally rich and gaining renewed attention across Jharkhand and other states—and Direct Seeded Rice (DSR), high-value vegetable crops were introduced in Karmatanr. While millets are well-suited for unpredictable climate conditions and low-input environments, their adoption in this village had declined over time due to low yields, labor-intensive processing, and limited market appeal. In contrast, vegetables offered a more practical and profitable option—better aligned with local preferences, easier to cultivate and market in a regimented way, and capable of generating higher cash income. Similarly, peach trees were replaced with guava and ber, better suited to the agro-climatic conditions. Inspired by the successes of nearby villages, banana plantations were introduced for the first time in Karmatanr.

"Ye sirf kheti ki baat nahi hai, ye jeevika ko sthir karne ki koshish hai" (This is not just about farming; it’s about stabilizing livelihoods), said Dr. Mahesh Dhakar, Scientist (Fruit Science), ICAR-RCER, one of the architects behind the model. He was visibly excited—Karmatanr had been selected as a pilot site for the Integrated Farming System (IFS), transforming it into a living laboratory where science and tradition would converge.

The Integrated Farming System is a pilot initiative by the central government, being tested through agricultural research institutes like ICAR-RCER. It involves studying a representative farmer's year-round activities—such as crop production, livestock rearing, fruit plantations, fisheries, and more—to understand how these components interact and support one another. Based on this analysis and the farmer’s aspirations, the institute suggests gap-filling interventions to maximize land use and income potential. The insights from these pilots will help shape future schemes and policies suited to specific agro-climatic zones.

Photo: Dr. Mahesh Dhakar Scientist (Fruit Science), ICAR-RCER explaining the components IFS

With projected incomes of ₹1,20,000 to ₹1,50,000 per hectare over the next 8–10 years, calculated by the scientist from ICAR-RCER, this model promises a future where we wouldn’t just survive—we would thrive.

Scaling Up: A Village Poised for Transformation

A solar-based Lift Irrigation (SLI) system, which we installed in 2021 in Karmatanr, has already brought 15 acres of farmland under irrigation—marking a significant shift for the 52 Santhal families living there. The system, powered by a 5 HP pump, was set up at a cost of ₹5.5–7 lakh, including the outlay for solar panels, pipes, and distribution mechanisms. Unlike diesel pumps, which are expensive and unsustainable, this solar model offers consistent, low-maintenance irrigation and is expected to last for 25 years.

Photo: Solar Lift Irrigation in use at the village of Karmatanr

This initiative was more than a technical installation—it was a community endeavor. Twenty-five families with land under the command area of the pump have been cultivating crops using assured irrigation. These families had already collaborated with us at PRADAN since 2018, successfully transplanting Amrapali mangoes through MGNREGA two years earlier.

To ensure sustained functioning and equitable benefit-sharing, Water User Groups (WUGs) were formed during the installation process. These groups include landowners whose fields fall within the SLI command area. Before forming the groups, we conducted awareness sessions and exposure visits to help villagers understand the system, their financial and social contributions, and the governance mechanisms.

These WUGs operate with well-defined norms. Members collectively decide on crop choices, sowing schedules, and grazing regulations to prevent damage from cattle. A locally chosen operator—typically someone interested in farming, technically inclined, willing to stay in the village, and not dependent on seasonal migration—manages the day-to-day operations. The operator maintains a ledger, tracking water usage, maintenance costs, and user payments via a coupon-based system, where users purchase time slots (e.g., 15 minutes) based on their irrigation needs.

To ensure accountability, WUGs meet 2–3 times a year, overseeing water distribution, maintenance, and infrastructure safety, including preventing accidental electric shocks—especially to children. These groups also promote better crop practices, integrate emerging technologies, and link farmers to Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs), ensuring continued evolution beyond basic irrigation.

But this transformation isn’t without challenges. As we plan to expand irrigation by tapping into the nearby Tirupati stream and introduce multi-tier farming with climate-resilient crops like Mulberry, Niger, and indigenous pulses, we face logistical and environmental complexities. In summer, when the stream dries up, a natural sunken bed with a stone base—a feature of the streambed—prevents percolation and acts like a pond. The large catchment area helps refill this basin even after it dries, ensuring a near-continuous water supply within 24 hours of a rainfall event.

Photo: Tirupati stream

The villagers are adjusting to crop planning seasonally. In summer, they opt for low-water-use crops like cucumbers, gourds, and climbers, often cultivated with drip irrigation. In the monsoon, they achieve 100% irrigation coverage, while in Rabi, about 70% of the land can be reliably irrigated.

The terrain of Karmatanr—undulating and located in Agro-Climatic Zone VII (Eastern Plateau and Hills Region)—features erratic rainfall, poor soil moisture retention, and limited groundwater recharge. These conditions make our SLI system even more critical. The near-flat terrain also reduces the lifting height required, allowing our SLI to cover more area than usual—up to 15 acres instead of the standard 12.5.

Assuming a return of ₹1,000 per 0.009 acre, vegetable cultivation during the peak season can generate around ₹12.5 lakh for 12.5 acres to 15 acres of cultivated land. Even with conservative estimates, a well-functioning SLI-supported farm like ours can yield approximately ₹10 lakh from Rabi crops alone for 15 acres of land. Additionally, during drought years, it can still ensure Kharif paddy cultivation, bringing in an estimated ₹5 lakh. However, to fully realize this potential, we must address several external challenges: reduced labor availability during marriage seasons, crop damage from stray cattle, difficulties in repairing equipment due to remoteness, and poor road connectivity that hampers access to markets—especially for perishable cash crops.

Still, the optimism in Karmatanr is palpable. With governance systems like our WUGs in place, efficient use of renewable water, and our willingness to adapt crops to shifting seasons and climate patterns, our community is now aiming higher—seeking efficient water storage, integrated livestock farming, and even a research partnership with ICAR.

A Future Within Reach

With support from partners like PRADAN, Axis Bank Foundation, and ICAR-RCER, what once seemed like a distant aspiration is now unfolding on the ground.

As the sun sets over Karmatanr, the multi-tier farm rises against the horizon—a visible marker of change in motion. While the long-term results are yet to come, there’s growing confidence that this land will continue to give back, season after season.

Photo: Layout for multi-tier farming in one hectare (2.4 acres) of land

What’s emerging in Karmatanr isn’t just a local success—it’s a spark for something much larger. The insights, innovations, and collective will taking shape here are setting the stage for similar transformations across Bihar and Jharkhand. Dozens of project villages stand to benefit—reimagining agriculture, strengthening local institutions, and unlocking economic confidence for thousands of smallholder families.

In this challenging yet hopeful landscape, the journey from survival to sustainability has begun—and Karmatanr is just the starting point.

Footnote:

*Agriculture Production Cluster approach- The Agriculture Production Cluster (APC) approach envisions that each village or hamlet will have a Producer Group (PG) comprising 30–120 farmers engaged in synchronized crop production aligned with market demand and regimented practices. Ideally, all PG members will be part of a Farmer Producer Organization (FPO), with 3,000 producers forming an APC of around 10,000 producers. An intermediary structure, known as Micro Production Arrangement (MPA), comprising about 250 producers, will facilitate seasonal meetings to support collective decision-making around 3–4 key crops, grazing control, and governance-related activities. APCs may also include FPOs focused on small ruminants, fisheries, or other enterprises. The primary objective is to generate marketable surplus, improve returns through synchronized production, and enhance farmer incomes by providing services such as timely access to quality seedlings, crop protection measures, and doorstep marketing support through PGs or FPOs operating within the cluster.

About the Author