A Tale of Two Villages: Growing Back Greener

Sritam Sankar, Executive, PRADAN

Introduction

In the year of 2024, in the fields of two villages in Odisha, an experiment was unfolding. Farmers were asking themselves: could their traditional, non-chemical practices hold their ground when compared with a Regenerative Agriculture (RA) approach? The goal was simple yet ambitious—to test whether RA could enhance mustard yields with minimal investment, while also enriching the soil and keeping pests away

Karksmaska, a small village in Bandhapari Gram Panchayat of Lanjigarh block in Kalahandi district, and Umej village in Lanjee Gram Panchayat of Biswanathpur block in Kalahandi district, have long struggled with a lack of irrigation facilities, poor electricity supply, and geographic isolation; challenges that have persisted for generations.

More About Karksmaska

Perched high on a rugged mountain at an elevation of over 610 meters from sea level, Karksmaska is an isolated village, accessible only after traversing a breathtaking yet difficult terrain. Breathtaking, because I had recently moved to Kalahandi after completing my Development Apprenticeship in Ghaghra, Jharkhand, and was now exploring this new landscape. On one of my leisure days, I decided to explore the area and that’s when I discovered Karksmaska.

Photo. Jayvanta Narbad Patre plucking her brinjal harvest

What appeared beautiful at first glance revealed a far more complex reality once I stepped inside the village. Karksmaska is home to 55 households, spread across two hamlets, primarily belonging to the Majhi community—classified under the Kutia Kandh, a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG). Agriculture is the mainstay here, but without irrigation, farming is limited to paddy and just enough for self-consumption. The harvest barely sustains families, and despite being labour-intensive, it yields too little to support their lives. Once the paddy season ends, men often migrate to southern India to take up daily-wage jobs, an uncertain and exhausting struggle in itself. This migration leaves women behind, burdened with the dual responsibility of managing the household and the land, often with very little support.

I spoke to villagers in my personal capacity, listening to their struggles, hopes, and aspirations. Upon returning, I spoke to my colleagues and learned that PRADAN hadn’t begun work in Karksmaska yet mainly due to the difficulty in accessing the village.

Start of something new

I wanted to start working in the village, though convincing my team was not easy. It took several rounds of discussions and many questions were raised. Some wondered if the terrain was even accessible—would our women cadre, the Community Resource Persons, be able to reach the hamlets regularly? Others pointed out the absence of strong markets in Kalahandi. Unlike Jharkhand, where each Gram Panchayat has a weekly market in one place or another, in Kalahandi only one market is held in a week, and that too in a single location. Marketing produce, therefore, was a challenge. The concern was, even if production improved, how would the farmers sell? My argument was simple: if we could support them in solving their marketing issues, half the problem would already be addressed.

What encouraged me the most was the community’s own response. They were enthusiastic, open, and willing to try something new. I still remember meeting Guthli Majhi, a resident of Karksmaska village,—relatively active, already practicing vegetable farming in her homestead. She expressed a clear interest in working with PRADAN, and her willingness reassured me that there was real potential in this village. Slowly, my team began to agree, and I decided to take responsibility for the interventions myself. I was excited.

Experience with the villagers

“Dada ame dhan chaas korsu, Kala chaas ke aka khaesu. Kichi time ne dorkar podle take ame biksu. Sorsu chas bhi korsu, je amal adhik nai aschi” (We grow paddy, eat from it, and sell a little as well. We also cultivate mustard sometimes, but the yield is not that much), said Guthli in my interaction with her.

Further discussions, individually with other villagers and in group discussions helped me understand the ecosystem. The villagers grow paddy for sustenance, then migrate, and those who are left behind broadcast mustard seeds and leave them to grow without any interventions. While chemical fertilizers are not used, the use of FYM (Farm Yard Manure- cowdung and goat dropping) is also minimal, mainly confined to homestead lands where livestock are kept.

Photo: A glimpse of pests in Non-RA mustard field

The nearby villages in the region also cultivate cotton and maize, but Karksmaska lags behind. In the absence of proper electricity facilities, farmers here struggle to set up irrigation systems, which are critical for cultivating these crops. Without irrigation, cotton and maize cannot thrive. Moreover, poor road conditions and the rough terrain discourage cotton vendors from visiting the region, making it difficult for farmers to sell their produce.

During my discussions, I learned that villagers here cultivate mustard, but the yield was relatively low—around 250–300 kg per acre. In comparison, the state average in Odisha stands at nearly 400–450 kg per acre, while in Ghaghra block of Jharkhand, where I had prior experience with Regenerative Agriculture (RA), farmers were harvesting a yield of 450–500 kg per acre. The difference was striking. In Ghaghra, farmers practiced RA interventions, which played a role in improving soil health and productivity. Here, however, most households simply broadcasted seeds and left the fields unmanaged, which explained the lower yields.

With nearly half the households engaged in mustard cultivation across 30–35 acres, I saw an opportunity to demonstrate RA’s potential. Community members were already against chemical farming—so much so that even if fertilizers were given for free, they would not accept them. For generations, they have kept their lands chemical-free and wanted to preserve them that way. This made RA a natural fit.

That said, a major constraint here is the lack of irrigation facilities. Because of this, we could not integrate super compost, one of RA’s most critical components. Super compost boosts microbial life in the soil—microbes that are naturally present but whose population has drastically declined over time. Without irrigation, applying and activating super compost becomes difficult. Yet, even without this component, villagers saw scope in experimenting with RA to improve mustard yields while nurturing their soils.

My strategy was an experimental approach with no risk to the community. The farmers had nothing to lose by trying bio-inputs, but a lot to gain in terms of yield, soil health improvement, and pest control. The community members were also eager to try RA techniques as it promised better yield without chemical inputs. For any PRADANite, beginning work in a new place is never easy, one has to get acquainted with the community and the terrain, and spend time building trust. In this case, the active community members helped me mobilize other women farmers in the village.

Photo: A glimpse of one of the planning meetings with community members

The community members like Guthli Majhi took the lead in mobilising other households to try mustard cultivation in the late Kharif season using the Regenerative Agriculture. Hence, in August 2024, began the planning of mustard cultivation using the method with 22 households across 27 acres.

Intervention around Regenerative Agriculture in the village

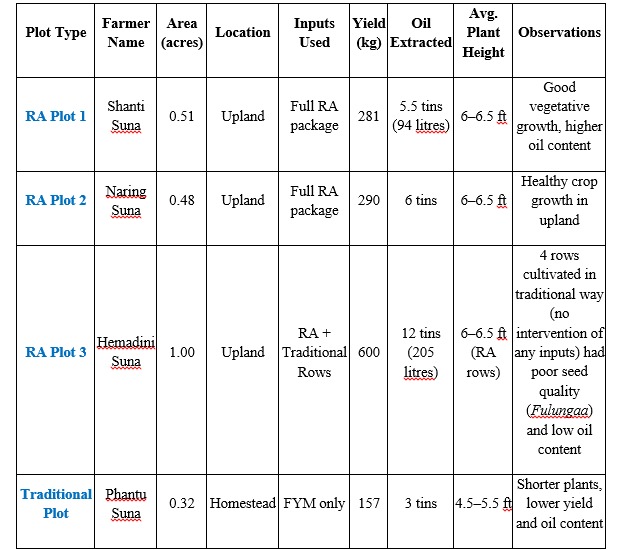

By the end of September 2024, the broadcasting of mustard seeds began, followed by several Regenerative Agriculture interventions that the farmers themselves prepared and applied:

- Seed treatment (Trichoderma & Pseudomonas): This was done to ensure better germination and protect the seeds from common seed-borne diseases, giving the crop a healthy start.

- Jeevamrit application: Applied once within 15–20 days of broadcasting, Jeevamrit supplies the young plants with nitrogen, which is crucial during their vegetative growth stage. It also enriches the soil with beneficial microorganisms that support long-term soil health.

- Agniastra spraying: Farmers carried out 2–3 rounds of this herbal pesticide from 30–35 days after sowing, with gaps of 8–10 days. Agniastra is easy to prepare in large quantities and helps control the wide variety of pests that typically attack mustard.

- Multi-Seed Extract (MSE) spraying: During the grain-filling stage, one to two rounds of MSE were used to boost nutrition. Prepared by grinding nine different seeds—three cereals, three pulses, and three oilseeds—it provides a balanced mix of nutrients that the plant requires during flowering and grain development.

The process was long, but the community members remained deeply invested. Each round of intervention was accompanied by discussions and hopes for a better harvest. With a total investment of about ₹350 per acre across 27 acres, involving 22 community members, the effort resulted in an overall yield equivalent to ₹11,000 of mustard seed, that is around 400 kgs per acre as compared to 250-300 kgs per acre earlier.

Photo: Mustard cultivation in Karksmaska using RA technique

With time, just before harvesting period the community members started noticing significant improvements in the mustard crop compared to previous years:

- Improved plant growth: The mustard plants in the RA plot appeared healthier, fresher, and more robust compared to previous years and to the adjacent plot where RA techniques were not used. In contrast, the plants in the non-RA plot looked withered and noticeably smaller.

- Reduction in pest infestation: Sawfly infestation, which was commonly observed in non-RA plots, was significantly reduced in the RA fields. In traditional plots, sawflies were easily visible, especially along the borders; we could spot them just by standing at the edge of the field, given how widespread they were. In contrast, in the RA plots where Agniastra had been applied, the scenario was notably different. The community members, cadres, and I had to walk deep into the field to spot even a few sawflies. The difference was stark—Agniastra had clearly curbed the infestation. It wasn’t just data; it was something we witnessed and experienced ourselves while walking through the fields.

- Better yield and grain quality: The mustard pods locally called "Sengha" were larger, and the grains were slightly bigger compared to non-RA plots. Additionally, the grains of RA plots were darker in appearance, indicating higher oil content as informed by the community.

Photo: Darker grains (below of RA plot) compared to non-chemical plot above

To quantify the impact, we collected yield data from two plots:

- RA-intervened plot (Plot A): 1m² sample yield = 260gms of mustard grains

- Non RA, non-chemical plot (Plot B): 1m² sample yield = 150gms of mustard grains

Photo: Weight measurement of 1m² sample yield

Extrapolating to total plot size:

- Plot A (0.78 acres) = 529 kg yield

- Plot B (0.46 acres) = 131 kg yield

The RA plot yielded nearly double the mustard compared to the non-RA, non-chemical plot. This result was surprising both for us and the community, supporting our experimentation and belief in RA practices.

Even though our experience with RA was good, we also faced some challenges mentioned below:

Challenges and Strategies:

One of the key challenges was the introduction of bio-inputs, as the women were using spray machines for the first time. Each woman had to manage, on average, one acre of land, and applying bio-inputs required operating heavy spray tanks. About eight rounds of spraying were needed per acre, with each tank holding 15 litres of liquid. Carrying and spraying such weight repeatedly was physically demanding, especially for women who were new to this kind of agricultural work. The machines were hired from the tool banks of other SHGs, supported under the WATER project in collaboration with HDFC Bank Parivartan.

Photo: Community member spraying bio-inputs in her land

Integrating supercompost (Shakti Khata) in mustard fields was also difficult due to the absence of irrigation facilities as the compost could not blend into the soil effectively. Additionally, exposure to direct sunlight could kill the beneficial microbes present in the bio-inputs.

To overcome these constraints, we mixed the bio-inputs with gomutra (cow urine) and applied the solution using the spray machines. This approach ensured better absorption and protected microbial activity despite the lack of irrigation.

Simultaneously, efforts were made to improve the village’s irrigation infrastructure. A 0.5 HP solar lift irrigation system is being introduced under the WATER project, to further address the irrigation challenges and enhance agricultural resilience.

A key learning was the community’s mustard marketing practice. Instead of extracting oil, farmers sell mustard directly to local vendors at ₹50 per kg and purchase packaged oil. In the future, we plan to explore ways for the community to extract, use their own oil, as well as sell in the market earning around ₹28,000 from a plot size of around 1 acres.

Key Learnings and Future Prospects:

- Scaling RA Practices: Since mustard is cultivated on a large scale in Karkamaska every year, continuing RA interventions through a cluster approach by forming groups of two to three villages to enhance the villagers’ bargaining power will be easier and more impactful, as the community is already convinced of the results.

- Community Ownership: Community members actively participated in the planning, preparation, and application of bio-inputs, demonstrating their growing confidence in RA methods.

- Addressing Market Linkages: Future work will focus on value addition (such as mustard oil extraction) and exploring better market linkages.

Conclusion: This mustard cultivation experiment in Karkamaska validated the effectiveness of RA approaches. The improvements in yield, plant growth, grain quality, and pest control demonstrated that “Regenerative agriculture works”. More importantly, the community and the team is also convinced and motivated to continue RA interventions in future crops.

Despite the village’s challenges—scarce water, limited supply of electricity and geographic isolation—the community members showed great excitement for adopting improved agricultural practices. Their willingness to experiment, invest and take ownership of the process marks a significant step toward sustainable farming and improved livelihoods.

More About Umej

Umej is a remote village tucked away in the Lanjee Gram Panchayat of Lanjigarh block, Odisha, about 20 kms from the block headquarters at Biswanathpur. With just 28 households and a population of 80 people, the community is primarily from the Scheduled Caste (SC) group.

Agriculture is the village’s lifeline. On their plots of around 2-3 acres per household, farmers cultivate paddy, arhar, horse gram, black gram, sunflower, cowpea, and a variety of rainfed vegetables.

Set in the seventh Agro-Climatic Zone, at an elevation of around 580-585m from sea level, Umej’s farming practices remain deeply traditional, that is, no use of chemical inputs in their agricultural land. Cultivation depends on low-input, rainfed methods, with only small quantities of cow dung and goat droppings used as manure, applied pit by pit. On homestead lands, farmyard manure is added more regularly. The red and laterite soils here, nourished by an average annual rainfall of 1,300 mm, support agriculture, but only just.

Challenges and working together

PRADAN has been working in the region for more than a decade now. Earlier, the village struggled with inadequate irrigation facilities. In 2012, a Diversion-Based Irrigation (DBI) project was installed, which remained functional until 2019, offering much-needed relief to the farming community.

However, the system was eventually damaged by wild animals, particularly elephants leaving the village once again without a functional irrigation setup. Although discussions about reviving irrigation came up from time to time, no concrete solution emerged until May 2025. That was when, through convergence with the Odisha Agro Industries Corporation Limited, Government of Odisha, four micro river lift irrigation points were established.

This breakthrough was supported by PRADAN’s facilitation, raising awareness, mobilising people, organising exposure visits, guiding site selection, training farmers, and creating linkages with the Department of Agriculture and Farmers’ Empowerment, Government of Odisha.

Under this initiative, the government invests ₹10,000 for Scheduled Caste (SC) households and provides assets worth ₹3.15 lakh (such as solar or electric pumps). With this support, a command area of 40 acres has been developed, bringing long-awaited relief to villagers and strengthening their agricultural system.

Context: Sunflower Cultivation Practices

During Kharif, farmers in Umej cultivate maize on their homestead and upland plots, usually covering about 0.5 to 1 acre. Sunflower is a major late-Kharif crop, sown between the first and mid-weeks of October and harvested in January. Around 15–16 households, each with an average of 1 acre, have been growing sunflowers traditionally, using only farmyard manure (FYM).

To maintain soil health, farmers follow a rotational cropping pattern, cultivating sunflower for 2–3 years, followed by pigeon pea for the next 2 years. Hybrid seeds are purchased from the local market, though no chemical inputs are used. Sunflower is mainly grown in upland and homestead areas, with yields averaging around 5 quintals per season in homestead plots and 4–4.5 quintals (400-450 kgs) in upland areas. With a market price of ₹50 per kg, and an investment required is relatively modest, about ₹1,000–1,500 per acre depending on the seed variety. The harvested seeds are processed for household oil consumption through commercial extraction units in Kalyansingpur, Rayagada, Odisha.

Regenerative Agriculture Pilot: Overview

In 2024, PRADAN initiated a Regenerative Agriculture (RA) pilot for sunflower cultivation in Umej, channelled through Bio-Resource Centres (BRCs). Convincing the villagers to participate was not difficult—years of PRADAN’s presence in the region had already nurtured a strong bond of trust.

The first BRC was also established in September 2024 with support from the HDFC Parivartan’s WATER Project, which provided ₹10,000 in funding. An SHG named, ‘Maa Brundabati’ took charge of running the centre, which focuses on producing natural, eco-friendly farm inputs such as vermicompost, super-vermicompost, Jeevamrut, multi-seed extract, Ghanjeevamrit, Agniastra, Mahulastra, and more.

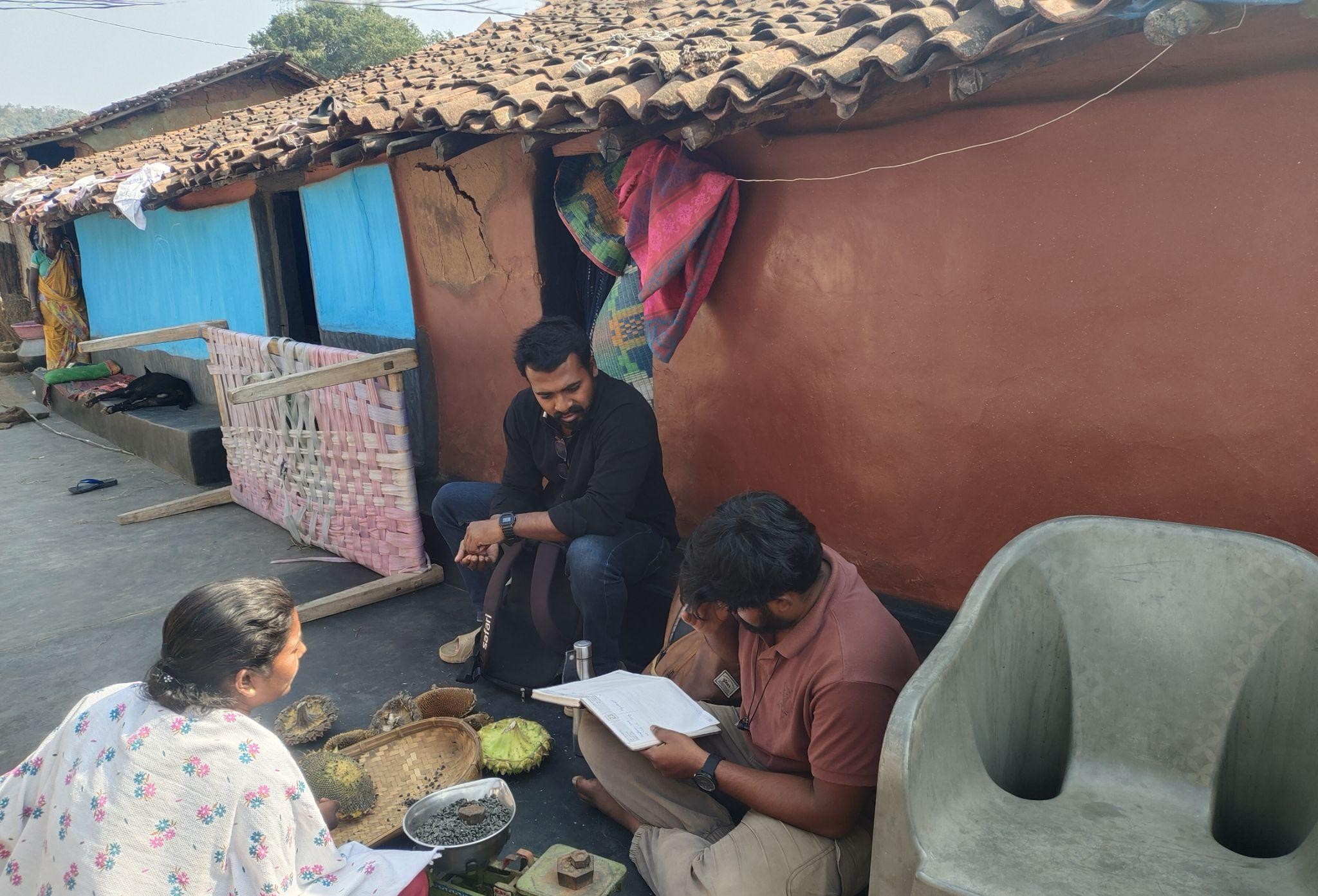

Photo: Community members along with the staff from PRADAN in the field

Planning and implementation were carried out jointly by PRADAN and the PARAAB Farmer Producer Company (FPC), an FPC facilitated by PRADAN. Together, they worked on production planning, trained SHG members in preparing bio-inputs, conducted technical sessions, and enabled participation in RA forums and exposure visits. The FPC also supported the SHG in generating demand, packaging, branding, and transporting their products.

The BRC is steered by the FPC itself: PARAAB FPC places orders with the centre, markets the bio-inputs within the community, and retains a small margin to sustain operations.

The Intervention

Photo: Sunflower cultivation in Umej using RA technique

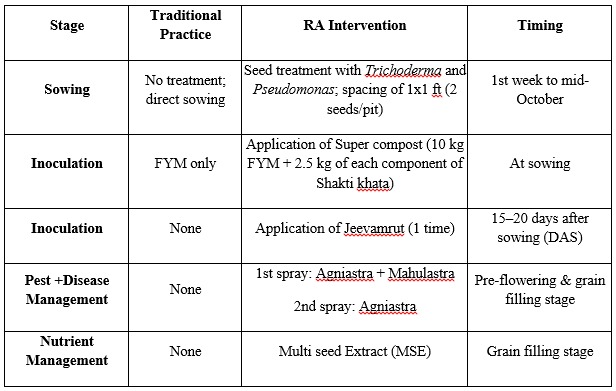

The community members planned Sunflower Cultivation in RA with 8 households in 6 acres (tracked 3 RA plots: 0.51 acres, 0.48 acres, and 1 acre)

Super compost Components like Trichoderma, Pseudomonas, Mycorrhiza, NPK Consortia & PSB were also used during cultivation.

Comparative Yield & Growth Analysis

Photo: Calculating the weight of sunflower seeds

Regenerative Agriculture (RA) plots outperformed traditional plots even on upland terrain, areas typically marked by red or lateritic soils with poor fertility, low water-holding capacity, and complete dependence on rainfall, making them less suitable for cultivation. Seeds from RA plots were observed to be of better quality, they appeared darker in colour and fuller, whereas seeds from non-RA plots were often fulungaa (hollow and light). This was taken as an indicator of higher oil content and healthier vegetative growth. Particularly during the pre-flowering stage, when pest infestations such as borers, flies, and beetles are usually more severe, RA plots with applications of Agniastra and Mahulastra recorded significantly reduced pest attacks compared to traditional plots.

"Agot amke lagsi ae mati ne amalat adhik nai aas.. abe ame joebik ne korsu, sorsu pura kola duschi aau amalat adhik heisi. Emti lagchi mati ne jeban pheri aensi” (Earlier we believed that this land could never give us good yields. But after adopting RA methods this time, the seeds came out darker and fuller. It feels as if life has returned to the soil), says Gomati Sona while talking about her RA cultivation.

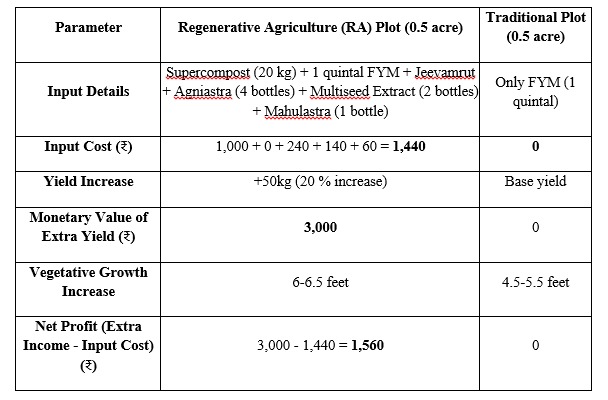

Cost Economics of Sunflower in RA vs Traditional for 50dec

The community’s response was overwhelmingly positive. With an additional investment of just ₹1,440 per 0.5 acre, the RA plots generated an extra income of ₹3,000 through increased yields. While traditional plots involved zero input costs, the RA intervention not only delivered higher yields and healthier crop growth but also strengthened farmers’ belief that it would help restore soil fertility. Encouraged by these results, they now plan to scale up the RA approach across more land.

Community Feedback and Observations

- Vegetative growth: Sunflower plants in the RA plots reached 6–6.5 ft, compared to 4.5–5.5 ft in non-RA plots.

- Seedling practice: Planting a single healthy seedling per pit resulted in better growth and yield than the traditional practice of using two seedlings (community experience).

- Soil health: Since no baseline data on soil health was collected, it is too early to comment on measurable improvements. However, farmers generally believe that continuous sunflower cultivation depletes soil fertility, which is why rotational farming is practiced. In the context of Kalahandi, pigeon pea plays a crucial role—it is naturally suited to hilly terrain, resilient under shifting cultivation practices, and deeply rooted in local traditions. Unlike vegetables, which are harder to grow in such landscapes, pigeon pea is both culturally significant and agronomically adaptable, making it an essential crop for sustaining soil health and livelihoods.

- Pest infestation: Pest attacks (borers, beetles, flies) are usually high during the pre-flowering stage, but RA plots recorded a significant reduction due to applications of Agniastra and Mahulastra.

- Seed quality: Farmers like Kiran Sona and Gomati Sona observed that RA seeds were darker in colour, which they believed indicated higher oil content.

- Yield observations: While vegetative growth and yields were higher than expected, farmers noted scope for improvement during the flowering and grain-filling stages. Heavy rainfall during harvesting also affected outcomes.

Key Learnings

- Thinning (1 seedling/pit)- Farmers usually plant two seedlings in a single pit, which often leads to competition for nutrients and weaker growth. On the other hand, placing only one seedling in a pit brings the fear of crop failure, if it does not germinate, there is nothing left to cultivate. Thinning provides a balance: sowing two seedlings and then removing one after 10–15 days. This allows the stronger plant to grow freely and deliver better yields. A few farmers who tried this method earlier reported healthier plants, making it a promising practice for the future.

- Pre-sowing documentation- Proper documentation before sowing is essential for building strong evidence. Tracking soil health data, recording Brix index calculations, and maintaining detailed field records help in assessing both the current condition and future outcomes. Such practices ensure that interventions can be measured and improved systematically.

- Vegetative growth vs. yield- The current cycle showed strong and visibly distinct vegetative growth. However, the focus for upcoming interventions will shift towards yield enhancement. One possible solution is using bio-inputs such as Multi-seed Extract B or Ondatonic (egg tonic), which are known to improve productivity. The challenge, however, lies in their preparation—ingredients are hard to find, the process is costly, and additional effort is required. Despite these hurdles, farmers see potential in using such inputs for better harvests.

Looking ahead, the next season offers an opportunity to plan cluster-based RA sunflower cultivation, which will not only strengthen collective learning but also create visible impact at scale. To ensure scientific rigor, soil testing will be incorporated both before and after cultivation, helping track changes in soil health more accurately. Progress will be systematically documented through photographs and yield data, providing concrete evidence of outcomes. Over time, these efforts will enable RA sunflower plots to evolve into exposure sites, inspiring and equipping farmers across the block to adopt similar practices.

Conclusion

The regenerative agriculture pilot in Umej has delivered encouraging results. Despite the challenges of upland terrain, the RA plots recorded higher yields, stronger plant growth, improved oil quality, and reduced pest infestation. These outcomes demonstrate the strong potential of RA interventions for wider scaling. Going forward, sustained technical support, systematic evidence tracking, and the integration of community experiences will be critical to ensuring long-term success and expansion.

Early Successes with Regenerative Agriculture

The stories of Karksmaska and Umej show that regenerative agriculture is not just a set of techniques, but a pathway to resilience for communities. In places where isolation, poor infrastructure, and ecological fragility have dictated the rhythm of life for generations, RA has opened new possibilities; boosting yields, improving soil health, and rekindling farmers’ belief in their own land. What began as an experiment has now sown the seeds of confidence and collective action. If nurtured with continued support and evidence-building, these efforts could mark the beginning of a larger shift where even the most remote villages lead the way in reimagining agriculture for a sustainable future.

About the Author