The Water Queens of Binkarwa: Taps, Grit, and a Village Reclaimed

- Astha, Communication Expert, PRADAN

Photo: Left to right – Anjali Kisku, Sunita Murmu, Shanti Devi, Phoolmati Hansda, and Prema Kumari

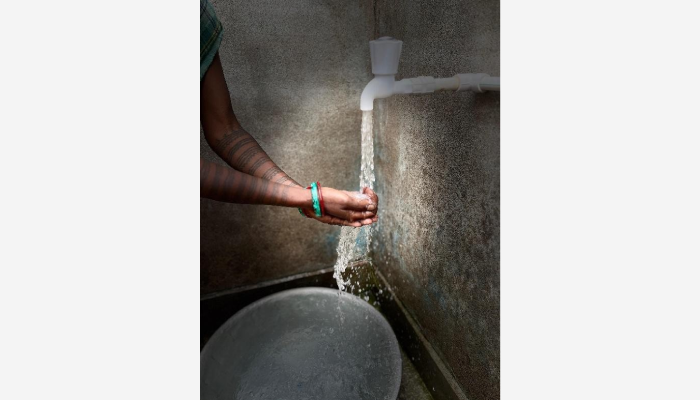

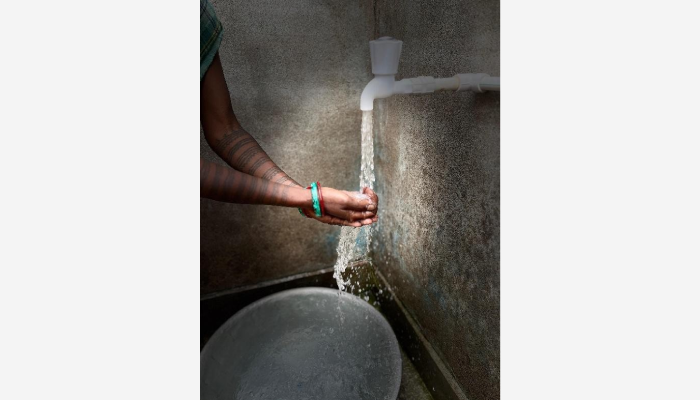

Photo: A woman holds clean water at her doorstep for the first time

Phoolmati Hansda, a resident of Binkarwa hamlet in Hazaribagh district of Jharkhand, spends several hours each day fetching water. Her journey covers nearly two kilometres, cutting across uneven plateaus, dipping into lowlands, and weaving through dense forest paths. For Phoolmati and many others in her hamlet, this daily trek is not just a routine but a reminder of the difficult terrain they mustcross to meet their most basic need - access to water.

Before dawn, she would set out, heart steeled for the physical and emotional toll ahead. Balancing heavy pots atop her head, Phoolmati navigated not just distance but the unpredictable passage; up rocky rises, through dense thickets, down into shallow valleys - her route a daily testament to both endurance and necessity. This grueling ritual, repeated with the rising sun, transformed her morning into a journey of survival, far removed from what should have been a simple routine.

Such a scenario is achingly common throughout the world, especially in India. Women often travel considerable distances to collect water, significantly increasing their daily workload. According to a report released by NSSO in 2018, 163 million people around the world do not have access to safe drinking water, a staggering number of them being women and young girls. During the day, they depend on sunlight to step out, collect water for their households, and make sure every drop is used carefully. Emphasizing again the sheer number of hours and opportunities lost to be able to educate themselves or tend to nurture them.

Photo - Sabhiya Tudu, resident of Binkarwa, celebrating the water access at her home.

But this morning, as water flowed freely from the tap, through infrastructure developed by the women and their community, and powered by a solar pump—everything changed. The tap was more than just infrastructure; it symbolized dignity restored and freedom from the endless chore that had defined generations. Phoolmati envisioned a future where her daughters would not begin and end their days at the edge of a distant pond. The hours once spent carrying water could now be dedicated to fields, family, and dreams. This transformation was not an accident; it was a movement led by the women of Binkarwa.

These women organized, informed, and partnered with local leaders to reclaim their time and reshape their futures. Damodar Mahila Sangh Samiti, a block-level federation founded in 2009 with 2,498 members, engaged in training and ongoing discussions with authorities to ensure their concerns were communicated effectively. The installation of the drinking water system was not just a technical achievement; it was a strong statement that no woman should have to carry the burden of water alone.

Photo: On-Site infrastructure

A solar-powered pump, a well plunging 30 feet into the earth, and a reservoir built for the next generation now stand as proof of what is possible when women take the lead. For the first time, water is no longer a distant dream but a reality at every doorstep. This victory was shaped by the efforts of Binkarwa’s water queens.

Building Together: The Road to Water Access

Securing safe drinking water for Chichikala; a village in Binkarwa hamlet predominantly inhabited by Scheduled Tribes, presented numerous challenges due to its remote location and unstable water supply. The journey of bringing safe drinking water to Binkarwa moved forward through a series of collaborative efforts.

In the initial stage, women from the village, supported by PRADAN reached out to the Public Health Engineering Department (PHED) in Hazaribagh to highlight the lack of reliable drinking water systems. PHED, also referred to as the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Government of Jharkhand is tasked with planning, implementing, and maintaining rural water supply schemes to provide drinking water to households. This includes initiatives such as the Jal Jeevan Mission's Har Ghar Jal (Tap Water for Every Home) program. This request was reviewed by the Executive Engineer and subsequently forwarded to the Sub-Divisional Officer for further evaluation.

To accurately assess the situation on the ground, PRADAN in partnership with PHED personnel, undertook extensive field visits. These inspections revealed a patchwork reality: while some villages already had functional pipelines and water tanks, others had incomplete installations or pending construction despite survey approvals. Recognizing these inconsistencies, PHED decided to revisit locations alongside the Junior Engineer and local contractors. This collaborative verification confirmed that the majority of the villages in question were either already included in existing plans or slated to receive water supply improvements in the near future.

At the same time, PRADAN implemented initiatives including training WASH mentors to conduct comprehensive assessments in three blocks of Hazaribagh district namely Churchu, Tatijharia and Padma, mapping the status of all water infrastructure, and identifying households that had not been included. Alongside this, efforts to strengthen partnerships with Panchayati Raj Institution (PRI) members and encourage active community participation helped ensure that every voice was heard and no household was overlooked.

Photo: Meeting of Damodar Mahila Sangh Samiti

With funding secured through the Water Accessibility & Enhanced Livelihoods for Women Project, supported by HDB Financial Services Limited, PRADAN began mobilizing the village’s governance structures. The project had been proposed with an annual outlay of ₹2 crores to support three teams across two districts in Jharkhand. Of this, the Churchu team of PRADAN received ₹65,42,412 for 2024–25, enabling focused work on strengthening community-led efforts for water access and improved livelihoods. To ensure local ownership, households were asked to contribute 10% of the project cost, a commitment that was formally endorsed during a Gram Sabha meeting. This process also led to the formation of a Water User Group (WUG), ‘Karam Tola Yapam Akhara Jal Samiti (KTJS)’, named after the local hamlet, signifying community-led management of the initiative.

Land donations by residents named Shanti Devi and Mahadev Tudu provided the site for a 30-feet well and a solar-powered water tank. Construction became a communal effort, with local families undertaking the digging and assembling, ensuring that wages remained circulated within the hamlet. The Karam Tola Yapam Akhara Jal Samiti took charge of constructing, maintaining, and governing the system. During the project, 43 households contributed a total of ₹43,000 as their required 10% share of the cost. Since the initiation of water connections, each household has been making a monthly contribution of ₹60.

“Aale do sob hod aa Suvidha lagi hudish keda. Lahate jun ligi da aagu aale ligi adi gi mushkil kami tahen kana. Roj setak da aagu are kichri safa ligi chalak kan tahen aale are jabtak aale uda le ruwad tabtak jo kichri tasi kate len he akan una rohodu aa, unka leka te aale uda to pura din khali gi tahena are gidra wa joton ho moj te bang huy dareya kan tahena. Jeevan do aadi gi kathin leka aayka kan tahena kintu nit do una ku kathinai to taynomena” (We always thought about everyone else’s convenience. Earlier, fetching drinking water was a backbreaking challenge for us women. Every morning, we would set out to collect water and wash clothes, and by the time we returned, the clothes we had left behind were already dry. The entire day would slip away, leaving our homes empty and our children uncared for. Life felt like an endless struggle. But now, those hardships are behind us), recalls Shanti Devi, her voice heavy with memories of the drudgery once tied to collecting water.

Photo: Shanti Devi in frame

For the first time, these women were not just seeking solutions but leading the change. Their persistence transformed a basic necessity into a community-led movement, ensuring a lasting impact for generations.

Water as a Catalyst for Change

The newly developed water infrastructure provides service to 46 households, as well as a primary school and community hall, through main and branch PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride) pipelines. These are integrated with a uPVC (Unplasticized Polyvinyl Chloride (uPVC), a pipeline network that supplies individual connections throughout the area. More than just a source of drinking water, it has become a foundation for economic opportunity. Local labor was engaged in the construction, providing employment and financial stability to many families. Around 15–20 laborers worked on the drinking water system for approximately 12 days a month over six months, with their earnings reaching around Rs. 25,200. The total cost of the solar drinking water project amounted to ₹ 22,56,850.

Photo: Celebrations post construction

Water is sourced from a dug well and extracted using a 3HP solar pump. Designed for a population increasing from 247 in 2023 to an estimated 335 by 2038, the system offers a planned operational life of 15 years. Each resident receives 70 litres daily, resulting in a total daily supply of 23,450 litres, distributed over four hours. The infrastructure features a 12,900-litre overhead reservoir for operational buffering and gravity-fed distribution

The KTJS has implemented a sustainable model for ongoing maintenance. Prakash Tudu, a locally trained technical operator, manages the system after receiving basic training during installation to handle settings and resolve issues. Further skill building will happen over time.

On 9th August, 2024, the well, solar-powered pump, and tank were finally completed, and the village celebrated with an inauguration ceremony. Traditional Santhal dance and songs filled the air as villagers, local leaders, federation members of Damodar Mahila Sangh, and staff members from PRADAN gathered to mark the achievement. “Ena kewal da bare tedo bang kana, mit sawn he katen jahana marang kami le huy chu wakada, Unkan kami jo kewal sanrachna tak simit banuwa kintu sob jon ku malik kana uduk eda.” (This wasn’t just about water. By coming together, we have built something bigger; a model of community ownership that goes beyond just infrastructure), says Sunita Murmu.

To strengthen awareness and community participation, wall paintings were created across all four villages. These vibrant visuals not only informed villagers and outsiders about drinking water and INRM initiatives but also served as tangible evidence of progress. By showcasing change on the walls, they fostered trust, belief, and optimism within the community while building a positive image of the project for visitors and potential supporters.

Photo: Inauguration celebration of the water unit

Photo: Wall paintings in the hamlet

Addressing Water Insecurity, One Pond at a Time

The transition of Binkarwa from experiencing water scarcity to implementing sustainable resource management demonstrates a process influenced by women’s involvement and new approaches. Two self-help groups (SHGs ) in the village, named Huter Baha Mahila Vikas Sangh and Jahir Ayiyo Mahila Vikas Sangh are further working with Damodar Mahila Sangh Samiti towards sustainable resource management. Beginning with the installation of the solar-powered drinking water system serving 46 households and essential community buildings, the project not only improved access to safe water but also generated employment and economic stability for local families.

Despite ongoing challenges like erratic rainfall and drought, the SHGs initiated Integrated Natural Resource Management Planning (INRM), organizing restoration efforts with PRADAN's support. Structured activities like site identification, training sessions, exposure visits, and the selection of community resource persons laid the groundwork for systematic water management and capacity building. Through participatory mapping and Ratri chaupal discussions, women contributed traditional knowledge and took an active role in identifying land for farm ponds and trench bunds, with 5–6 training sessions engaging 30–40 participants for a duration of seven days.

Photo: Women participating in INRM planning

Water, Ownership, and Decision-Making

With training in resource management, the community took bold steps to address water scarcity. In 2024, they built two farm ponds (100ft × 100ft × 10ft each) with a capacity of 7,80,000 litres; enough to irrigate 2 hectares of land—and developed 1.5 hectares of trench-cum-bund (TCB) systems on barren land. Located strategically, ponds in lowland areas with a gentle slope and TCBs in upland fields captured rainwater, prevented runoff, and gradually restored soil fertility. Fields that once lay uncultivated were brought back to life.

Building on this success, villagers constructed staggered trenches and check dams to further conserve water and protect against soil erosion. These interventions became lifelines, ensuring crops could survive even in dry spells.

The real transformation, however, came with the introduction of fish farming. Women received training to manage ponds not just for irrigation but also as income-generating assets. Integrated farming systems emerged: fish in ponds, vegetables along bunds, and crops in the fields. These layers of livelihood brought food security, diversified income, and resilience against uncertain weather.

Sunita and Phoolmati became landowners of these newly constructed ponds, something that had been nearly unthinkable in previous generations. "Nuwa gadiya jo ehob re pataw ligi le vyavhare tahenale, nit do haku asul ligi hon kami hijukana jo ki mit ten etak aa kamai riya jariya binawena. Pradan khon training jam sawn sawn te aale miten moj jeevika sen le laha kana” (These ponds, initially built for irrigation, are now being used for fish farming as a supplementary livelihood source. With training sessions provided by PRADAN, we are moving towards a sustainable and integrated livelihood), says Phoolmati Hansda.

Photo: Women of Binkarwa hamlet (Sunita Murmu, Shanti Devi, and Phoolmati Hansda)

Women trained as fish farmers transformed these ponds from mere water storage units into sources of livelihood. With integrated systems allowing for vegetable cultivation along pond bunds, these water bodies provided multiple layers of security—food, income, and resilience against water insecurity.

From Governance to Economic Growth

The most profound achievement emerged through the evolving roles of women within local governance. Where once they had been hesitant to voice opinions in public forums, women now stood at the forefront—leading village meetings, making financial decisions, and collaborating with government officials. Their quiet and often overlooked presence transformed into confident participation and influence, as they actively shaped the future of their community.

In August 2024, the community took a significant step forward by introducing 10 kilograms of fish seedlings into each pond. Four distinct breeds—Rohu (Labeo rohita), Katla (Catla catla), Mrigal (Cirrhinus mrigala), and Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella)—were carefully selected for their adaptability and market value. These fish are destined for sale in the Charhi market, located 8 kilometers from the village, promising new streams of income for local families.

Photo : Farm pond of Phoolmati Hansda

Women like Sunita Murmu and Phoolmati Hansda have already showcased how farm ponds can transform lives. Sunita’s pond not only produced 75 kgs of fish worth over ₹12,000 but also irrigated 7.4 acres of farmland, supporting eight households. Similarly, Phulmati earned nearly ₹14,000 from her first harvest of 85 kgs fish, while her pond irrigates 6.1 acres and benefits five families. Beyond nutrition and income, these ponds have become shared assets, strengthening women’s leadership in sustaining livelihoods.

Women have not only utilized the ponds for irrigation in their crop fields but have also cultivated a variety of vegetables—peas, tomatoes, radishes, and potatoes. Mustard crops have further supplemented household incomes. Notably, Phoolmati Devi earned ₹30,200 from cultivating potatoes on 0.5 acres of land and ₹10,500 from cultivating mustard on 0.5 acres decimals using the irrigation facilities available now, reinforcing the financial stability that agricultural innovation has brought to their lives. Similarly, four women farmers - Lalita Devi, Nisha Soren, Manju Devi, and Puja Kumari, initiated multilayer farming on 0.35 acres of land, growing bitter gourd and coriander, which fetched them about ₹75,000 last season. Building on this success, three of them have continued the practice on 0.25 acres this year with coriander, ridge gourd, and bitter gourd, expecting an income of around ₹60,000.

The growth extends beyond crops and ponds. As Anjali Kisko, a village resident, shares, “Nit jasti da hu yen khan aale ligi vibinn tarika riya jeevika rena sadhan khula wena joki aaleyaa jiveeka are gi majbut eda.” (With more water available, we now have different sources of income, which has strengthened our livelihood). From renewed fields to restored water sources, each effort is helping the community become more resilient and prosperous.

Challenges and Bottlenecks

Initially, villagers were reluctant to contribute financially, expressing that free water was available through the Jal Jeevan Mission and hence questioning the need to invest in new water infrastructure. What they ignored were the irregularity of supply, the challenges of maintenance, issues of water quality, and the long-term sustainability of sources. PRADAN communicated that labour costs would remain within the village; however, during construction, consistent attendance proved challenging. Despite the opportunity of local employment reducing migration, frequent absence from the site occurred, requiring daily engagement to ensure participation.

Irregular Gram Sabha meetings and the lack of contributions to the Water User Group (WUG) remain significant challenges, as highlighted by community members. Convincing stakeholders about water structure development has not been without hurdles. Communication and coordination often proved difficult, causing delays in village selection and project timelines. Procedural requirements further slowed the confirmation of suitable sites, while overlaps with existing or planned projects complicated efforts to select villages lacking functional infrastructure. These challenges are not yet fully resolved—they persist as ongoing issues the community must continue to engage with, finding ways to strengthen coordination, participation, and long-term sustainability.

Community-Owned Solar Water Supply with Low Carbon Footprint

A solar-powered drinking water system was implemented to address water inaccessibility for 46 households in Binkarwa, which were outside the conventional water supply network due to administrative and geographical factors. This initiative aimed to provide a reliable, decentralized, and community-managed water source, reducing dependence on external approvals and infrastructure that previously delayed access. By using solar energy, the system offers an alternative to electricity-dependent pumps, which can be unreliable in rural regions because of inconsistent power supply. The use of solar-powered water pumps avoids greenhouse gas emissions associated with diesel or electric systems and reduces reliance on fossil fuels, thereby lowering the community’s carbon footprint. The system is structured to optimize water use, limit wastage, and support equitable distribution. The combination of a solar pump with a community-owned water tank and well is intended for long-term sustainability by aligning energy efficiency with responsible resource management.

To understand the environmental impact of the solar-powered water system in Binkarwa, we estimated the carbon emissions it helps avoid. The village pump is a 3-horsepower unit (≈2.24 kW of shaft power). Accounting for an 80% pump–motor efficiency, its electrical draw is about 2.80 kW. Running for 4 hours a day year-round, that equals roughly 4,084 kWh of electricity each year. Using a grid emission factor of 0.757 kg CO₂ per kWh, the solar system avoids about 3.09 tonnes of CO₂ annually, or ~46 tonnes over 15 years—showing that, beyond ensuring drinking water access, it also meaningfully lowers the community’s carbon footprint.

This calculation highlights that beyond ensuring drinking water access, the solar-powered system also contributes to climate action by lowering the community’s carbon footprint.

Future Built on Community Strength

The successful completion of the solar-powered drinking water system in Binkarwa Village was not just about infrastructure—it was about reclaiming time, dignity, and possibilities. Water, once a source of hardship, has now become a symbol of resilience and unity.

Through solar-powered water systems, Integrated Natural Resource Management (INRM) practices, and fish farming, women like Phoolmati, Sunita, Anjali, Shanti etc. have not only secured water access but also claimed ownership of assets, diversified livelihoods, and reduced their community’s carbon footprint. These interventions reflect the broader vision of the AWARE (Access to Water for Rejuvenating Rural Economy) initiative, which champions women’s leadership in water access as well as assets in their name.

Photo : News clipping in a local newspaper

Under AWARE, women are mobilized into Self-Help Groups, Water User Groups, and federations where their voices shape decisions on water use, agriculture, and resource management. The initiative promotes asset ownership in women’s names, ensuring that benefits flow directly to them and reinforcing their identity as farmers and leaders rather than invisible contributors. By aligning with Panchayati Raj Institutions and state systems, AWARE strengthens inclusive governance, enabling women to participate in Gram Sabha discussions, negotiate with officials, and advocate for investments in water infrastructure.

"Nit do aale le ehob aakada kintu nit ho aale bhuparat kheti are aar hon eta lekan kheti le koraw eda. Aale are hon barya gadiya le benaw eda. Dak rena vyavastha te badlaw huyu kana kintu aale are hon bay bay te are nawa nawa yojna le benaw eda” (We have just started, but we are still practicing multi-layer farming and some cultivation. We are also constructing two more ponds. Access to water has brought some changes, but we plan to take on more initiatives gradually), says Prema Kumari, a resident of the Binkarwa hamlet.

Since the change is still in its nascent stage, a proper understanding of local governance is crucial for the community. Moving forward, the integration of fisheries, agriculture, and ecological sustainability will continue to enhance rural prosperity. More than anything, this journey reaffirms that when women are included in decision-making, entire communities thrive. Their voices, once unheard, now shape the future of their villages—one drop of water at a time.

About the Author