A Small Patch; A Big Harvest!

Bappa Mridha, Block Livelihood Coordinator, PRADAN

Special Input: Ankit Tandon, Team Coordinator, PRADAN

Introduction

“Mai punarjeevi krishi takneek 2024 se istemaal kar rai hu. Ye jameen aur paryaavaran dono ke lie achha hai. Harr kisaan ko ye takneek istemaal karni chahiye kheti karne ke lie” (I have been using regenerative farming techniques in my land since 2024. Regenerative farming practices sustains both the land and the environment and every farmer should use this method to ensure the sustainability of their farms and livelihoods), declared Jayvanta Narbad Parte, her voice steady with conviction as she stood amidst her thriving, emerald-green fields. I had come to see the condition of her agricultural plot, but what I found was more than just healthy crops- it was a life, a family, and land evolving in front of my own eyes.

I joined PRADAN in Madhya Pradesh in February 2024, and since then, I’ve been working with Jayvanta Narbad Parte. Like most in her community, Jayvanta—a 48-year-old farmer from Gaunajhola village under Khursud Gram Panchayat in Paraswada block of Madhya Pradesh’s Balaghat district—once depended solely on paddy cultivation. On her two acres of land, the annual harvest earned her no more than ₹20,000. In 2003, with a strong determination that would define much of her journey, she took up work as an Anganwadi Sevika. The job now brings in an additional ₹84,000 a year—a modest sum, but one that gives her family some breathing space. Life didn’t change overnight, but it began to find its footing.

For a family of seven—two children, two siblings, her in-laws, and herself—the income was barely enough to keep them afloat. As a widow, Jayvanta had to shoulder the dual responsibility of earning a livelihood and managing the household. The meagre earnings resulted in poor nutrition, unavailability of medicines in times of need, and limited access to education for her children.

Life was unforgiving. But Jayvanta? She was not willing to give up.

Meeting Jayvanta Narbad Parte, for the first time!

I came across Jayvanta in 2024, during a field visit to the village as part of my Regenerative Agriculture training. Tall and lean, with a sharp gaze and an even sharper voice, she carried herself with a rare mix of shyness and certainty—as if life had taught her to speak only when it truly mattered.

Photo. Jayvanta Narbad Patre plucking her brinjal harvest

“Bhaiya, hum log kaam karna chahte hain, apni kamai badhana chahte hain, lekin saadhan nai hai. Aap bataiye kya kar sakte hain?” (We want to work, we want to increase our earnings, but we lack the means. You tell us—what can we do?) Her words rang out with quiet authority. She wasn’t asking for sympathy—she was demanding solutions. I was momentarily taken aback. In a world where rural voices are often subdued or unsure, here was a woman, in a remote hamlet, challenging the status quo with a single sentence. It wasn’t defiance—it was clarity. A clear call for change.

That interaction stirred something in me. It pushed me to re-examine my own assumptions about ownership and aspiration. Over the following weeks, I spent more time in the village—speaking not just with Jayvanta, but with several other women and farmers, individually as well as in SHGs and Village Organisation (VO). Their stories were similar: the aspiration to earn a stable income, the frustration of working hard with little to show due to poor crop yields or limited market access, and a deep desire to lead a life of dignity.

Through these conversations, a pattern slowly began to emerge. While the challenges were many, what stood out was the firm belief with which they carried on—wanting to work for a better tomorrow, attending training sessions, and supporting one another in SHG meetings. It became increasingly evident that many among them already possessed the resolve and willingness to bring about change.

This made me reflect on our role as facilitators. Perhaps it isn’t about directing or leading change, but about connecting the dots—ensuring the right resources reach the right people, and creating the space for transformation to take root and grow.

I was determined—but also uncertain. The will to act was strong, yet the path ahead felt foggy and unfamiliar. Unsure of where to begin, I turned to my team. I confided in them, leaned into their experiences, and opened myself to their insights. Those early conversations became my compass. We discussed what had worked in similar villages—how building trust through consistent engagement was often more powerful than any technical intervention. They spoke about starting small: identifying one or two motivated farmers, focusing on demonstrations rather than discussions, and letting visible results speak for themselves. We also talked about listening more—about how real change begins by understanding people’s lived realities before introducing new models or approaches. These reflections helped shape not just what I did, but how I did it—with humility, patience, and a readiness to learn alongside the community.

Slowly, a realization dawned: before I could contribute meaningfully, I had to listen—to the land, its rhythms, its people. I needed to understand the landscape, the demography, and the very geography that shaped lives here. Only then could my efforts hold any real value.

More about Gaunajhola village, a village in Madhya Pradesh

Gaunajhola is a village of around 65 families belonging to the Gond community, in majority. With an average land holding of 1-2 acres, and dependency on rain-fed agriculture, most of the villagers only cultivate paddy during Kharif season while leaving the land uncultivated for the rest of the year.

Photo. Guanajhola at a glance

The region falls under the Chhattisgarh Plains Agro-Climatic Zone (MP-1), which is characterized by sandy-loamy and lateritic soils, moderate rainfall, and a tropical climate. While these conditions are suitable for a range of crops, the soil type is prone to erosion and has low water retention capacity, making it vulnerable to degradation without proper management. Over the years, excessive reliance on chemical farming practices has further depleted soil health—stripping it of organic matter and microbial activity. This has not only driven up input costs (fertilisers, pesticides, etc.) but also reduced long-term land productivity, resulting in a steady decline in both the quality and quantity of agricultural produce.

The moment of Eureka!

The training sessions I had attended initially opened my eyes to the potential of regenerative agriculture—farming practices that rebuild soil health, reduce dependence on chemical inputs, and increase resilience to climate uncertainties. The concepts struck a chord with me. And once my training ended, I figured this might be the best way forward for Gaunajhola and Javyanta given the ecosystem of the village. But I also knew that bringing them to life in the field would take more than technical know-how—it needed community trust and participation.

So, I returned to the village post my training program and started having long, open-ended conversations with the community. We spoke about the everyday struggles they faced—deteriorating soil fertility, rising costs of inputs, erratic weather, and growing vulnerability to pests and diseases. Slowly, a shared understanding began to emerge: the way things were going couldn’t continue. Interest in trying something different—something more sustainable—began to take root. In those early discussions, women like Jayvanta shared their doubts and hopes, their willingness to experiment if it meant a better future. Together, we explored what a shift to regenerative agriculture could look like. We discussed options for demonstration plots, natural inputs, and low-cost interventions that might work within their means.

Pause. Then uncertainty. Then experimentation. Finally, a decision.

The idea took time to settle in—and I didn’t want to rush it. It had to belong to them. It was their land, their livelihood, their risk. But early on, I sensed hesitation. Some were reluctant to give up practices they had relied on for years. Others were skeptical—wondering whether this new approach would actually work. A few openly voiced their doubts, questioning whether the risk was worth it given their already fragile situations.

That made me step back. I realized I had been too focused on sharing what I knew, without truly listening to what they needed. I needed to shift my approach—from offering solutions to asking the right questions.

So, on my next visit, I returned not with answers, but with curiosity. I asked about their crops and soil, their financial constraints, and the kind of labour support they could count on. Their responses were honest and revealing. Their soil, they said, had become tired—yielding less despite increasing use of chemicals. Input costs were climbing, but returns remained low. They wanted something that used less water, involved less risk, and could be managed with limited help from family members.

Amidst all these questions, I decided to explore the idea of regenerative agriculture in a net house with the villagers with the support from the Lohajharni SHG in Gaunajhola and the guidance of the PRADAN team.

Regenerative agriculture is a sustainable farming approach that restores soil health, enhances biodiversity, and builds climate resilience. It focuses on practices like composting, crop rotation, minimal tillage, and integrating trees and livestock. By reviving degraded land and reducing dependency on chemical inputs, it improves productivity and supports farmer livelihoods—making it especially relevant in tackling food security and climate challenges in regions like rural India.

However, one challenge remained. To establish a typical net house is costly and the initial costs range somewhere between Rs. 10,00,000- 15,00,000, a sum the villagers cannot afford.

After much diligent research, discussions, both within PRADAN and in the village one model stood out: the Kheyti Net House. It offered practical solutions to the very problems they had shared. It minimized chemical inputs, protected crops from weather extremes and pests, used water efficiently through drip irrigation, and could be handled by small households.

The Kheyti Net House model—developed by Kheyti, an organization that provides technical solutions to small farmers—offers a low-cost farming solution designed to increase crop yield and predictability. Kheyti not only supplies the infrastructure but also provides associated technical services, functioning as a vendor in the process. The model, covering 0.06 acres, is priced at ₹1,11,350. Of this, Kheyti contributes ₹63,000 as a subsidy or promotional support, in line with its mission to boost farmer incomes by mitigating climate risks through accessible technology. By subsidizing the model, Kheyti aims to make the solution affordable for marginalized farmers, thereby encouraging wider adoption and long-term impact. The remaining cost is covered through a contribution of ₹37,000 from PRADAN under the Women’s Economic Empowerment (WEE) project, and ₹11,350 mobilized from the community.

The model wasn’t just introduced—it was chosen. Together.

The Kheyti Net House Model

The idea of regenerative agriculture via a net house model—quite radical in its promise—began to take root within the five Self-Help Groups (SHGs) in the village. Among the first to embrace it were Jayvanta Narbad Parte.

The net house model offers a protective cultivation structure designed to optimize conditions for high-value crops. It is built on a sturdy foundation of auger anchors (cables) and concrete, supported by crimp pipe columns. Measuring 20 meters by 12 meters with a height of 2.5 meters, the structure is covered with a 30% shade net, which helps regulate sunlight and temperature. On a plot of approximately 0.06 acres, the net house can accommodate the cultivation of 500 to 550 plants. By moderating temperature extremes—heat, cold, and moisture—and minimizing pest infestations, the model supports year-round farming. Its implementation aims to enhance crop productivity, reduce the incidence of pests and diseases, and promote sustainable, protected cultivation of vegetables and other high-value crops.

Photo. Preparing Net House for cultivation

However, the implementation has not been easy. The training process, which began in early March of 2024 is rigorous and multi-phased. It began with planning and mobilization—baseline surveys were conducted to identify interested small and marginal farmers, sites were selected based on land suitability, sunlight, and access to water for drip irrigation, and community meetings were held to raise awareness about the model. Land preparation followed, with raised beds and proper drainage systems being established.

Training and capacity building are ongoing: farmers have been trained and continue to receive guidance on crop planning, irrigation, and pest management through on-field demonstrations and hands-on sessions, with technical support being provided throughout the crop cycles. Crop cultivation is underway—healthy seedlings are being transplanted, organic fertigation is applied, and eco-friendly pest control methods such as sticky traps and neem-based sprays are being used. Marketing linkages with local vendors will be facilitated, and farmers are being trained to maintain detailed crop and input records as part of the monitoring process.

The training was conducted in four structured phases to build farmers’ capacities in regenerative agricultural practices using the net house model. In the first phase, participants received hands-on training in land preparation, including bed formation, drip irrigation installation, and an introduction to the benefits of net houses and the regenerative agriculture (RA) model. The second phase focused on practical techniques such as root treatment, transplantation, and basal dose application. The third phase covered the preparation and application of bio-inputs like liquid jeevamrit, agniastra, and neemastra. In the final phase, farmers were trained in Integrated Pest Management (IPM), Integrated Nutrient Management (INM), harvesting techniques, and data management.

Photo. Kheyti Net House during cultivation- brinjal as a product

Inspired, resolute, and confident about the knowledge she has gained, Jayvanta Narbad Parte decided to take a bold step in March, 2024—she would cultivate a small patch of her land of 0.6 acres using the Net House model. This was the solution Jajvanta was looking for. As part of the Net House model’s regenerative approach to farming, Jayvanta Narbad Parte was trained in a variety of techniques that sought not just to grow crops, but to heal the soil. She learned to work with nature—using vermicompost and farmyard manure to nourish the land organically, embracing mixed cropping patterns to enhance biodiversity and restore soil vitality. Neem sprays, liquid Jivamrit, and simple traps replaced chemical pesticides.

But such decisions are never without friction. Her family hesitated. The land they had was modest, just enough to grow paddy for sustenance. What if this experiment failed? What if they lost even that? But Jayvanta had already made up her mind—she chose to cultivate brinjal on her 0.06 acres of land. She selected brinjal because it is more tolerant to heat, making it well-suited to the region’s climate. The crop offers higher yields compared to other vegetables and continues to produce over a longer duration. Additionally, its strong local demand ensures easier marketability and better income potential.

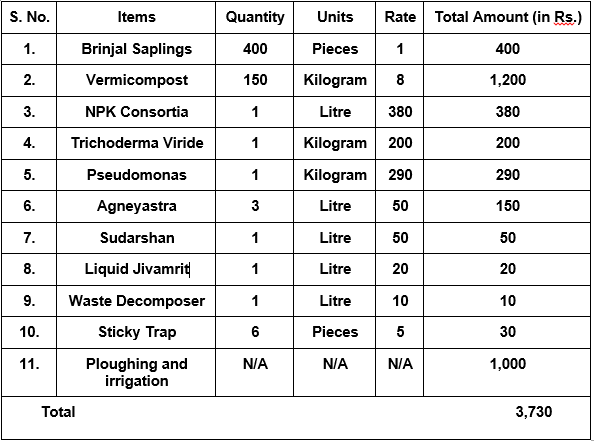

Cost for Net House Cultivation – 0.6 acres land (Regenerative Agriculture Model)

These items support brinjal cultivation by combining bio-nutrients, biofertilizers, and natural pest control. Brinjal saplings are the planting base, while vermicompost and Jivamrit enrich soil fertility. NPK (Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium) consortia, Trichoderma, and Pseudomonas improve plant health and disease resistance. Agneyastra, Sudarshan, and sticky traps offer natural pest control. Waste decomposer aids composting, increasing soil fertility and ploughing with irrigation ensures proper soil preparation and moisture. Together, these inputs promote healthy growth, reduce chemical use, and support sustainable farming at a total cost of Rs. 3,730. Jayvanta invested the money with the hope of a healthy produce.

Later, bio-fertilizers like trichoderrmaviride and pseudomonas fluorescens were introduced in her field for fungal and bacterial disease control, while root and soil treatments focused on rejuvenation through natural inputs. They enhance soil fertility, structure, and biodiversity, improving soil water holding capacity and aeration. Trichoderma viride and Pseudomonas fluorescens produce antibiotics and enzymes that suppress plant pathogens, reducing soil-borne diseases while enhancing plant growth and yield.

Ploughing was minimized to protect the delicate web of soil microbes; solutions like NPK consortia, jivamrit, waste decomposer, and soya tonic became tools of resilience, helping build robust plant health and integrated nutrition.

But this journey was not hers alone. Learning became a collective process—rooted in the everyday rhythms of the community. Farmers, including Jayvanta, gathered in small groups through Self-Help Groups (SHGs) and Village Organisations (VOs), forming learning circles where experiences were shared, doubts addressed, and techniques refined. They regularly attended refresher courses, hands-on training sessions, and peer-led discussions facilitated by PRADAN. These gatherings were more than just technical trainings—they nurtured a sense of shared purpose and collective growth, where each farmer’s success became the community’s gain.

Even as the Net House model began to show promise, one problem loomed large: water. Rather, the lack of it. Farming dreams wilt quickly without irrigation. In some places, the land was not properly leveled, which caused water to collect and created problems.

To address the issue of excessive water use in agriculture, a drip irrigation system was introduced in 2024 under the Women’s Economic Empowerment (WEE)* project, supported by the Gates Foundation and Reliance Foundation. This water-efficient intervention ensures consistent crop health while significantly reducing water consumption. Normally, 500,000 to 700,000 liters of water were used per 0.6 acres each season, though this figure could be lower in rain-fed conditions. With the adoption of drip irrigation and mulching techniques, water use was reduced by 45–50%, as observed in the farm. Under conventional methods, each plant required approximately 8.5 to 9 liters of water per day, which has now been brought down to about 4.5 liters with the new practices.

Drip irrigation works by delivering water directly to the root zone of plants through a network of pipes and tubes. This targeted approach minimizes water waste, as water is applied close to the soil—often under mulch—ensuring slow and steady absorption. As a result, moisture remains where it’s most needed, the surrounding soil stays relatively dry, and weed growth is discouraged. The system has complemented the Net House model effectively, contributing to a more sustainable and climate-resilient farming system.

Apart from this, several other efforts like accessing government schemes, Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana (PMKSY) to improve irrigation infrastructure, capacity building and encouraging community participation in irrigation management have become important tools to deal with the issue of lack of irrigation infrastructure.

Jayvanta Narbad Parte- Farming for the future

In March 2024, Jayvanta sowed 300 brinjal investing ₹3,730—including ploughing and labour. A gamble, laced with hope. She also received vital inputs—bio-fertilizers and natural treatments—from Saheli Khetkhaliyan Mahila Kisan Producer Company Limited (SKMKPCL), a Farmer Producer Organization (FPO) facilitated by PRADAN. SKMKPCL is a women-led Farmer Producer Organization based in Lamta, Balaghat, Madhya Pradesh. Established in 2020, it focuses on empowering women farmers through sustainable agriculture, natural farming, and improved market access. With over 1,000 women shareholders, the FPO promotes collective farming, organic practices, and value addition. It plays a key role in enhancing rural livelihoods and championing the leadership of women farmers like Jayvanta in agriculture.

From just 0.6 acres of land, Jayvanta harvested 8 quintals of brinjal and sold it at an average of ₹20 per kilogram. It brought in ₹16,000, in additional income from net house farming in one cropping cycle of around 3-4 months (March to June, 2024), a figure that was once unthinkable for such a small patch of land.

Photo. Jayvanta Narbad Patre with her produce

The contrast is stark. That very same piece of land, when used for paddy, had yielded barely 75 kilograms—bringing in a modest ₹1,000 at most. The difference isn’t just in numbers. It is in possibility!

“Abhi bhi vishwas nahi hota. Itni chhoti si zameen se ₹16,000 kama liye. Ab main punarjeevi krishi takneet ke zariye apni zameen aur bhi achhe se khejna chahti hoon, aur apne parivaar ko arthik roop se sahara dena chahti hoon” (I still can’t believe it. I have been able to earn ₹16,000 from such a small piece of land. I want to further cultivate my land using regenerative agriculture techniques and financially support my family), says a positively surprised Jayvanta.

Jayvanta is happy, constantly expanding her knowledge by following improved agricultural methods, inspiring the community, and becoming a role model for other farmers.

Jayvanta Narbat Parte’s journey has become a symbol of transformation in Gaunajhola village, Balaghat district, Madhya Pradesh. Inspired by her success with regenerative agriculture, three Self-Help Groups (SHGs) in the village have taken the first steps toward adopting similar practices—preparing and applying Jivamrit, a natural liquid fertilizer, for their paddy cultivation. Their shared goal is to enhance yields while caring for the soil and improving livelihoods. With hands-on training and ongoing support from PRADAN, these groups are translating inspiration into collective action—demonstrating how one farmer’s leap of faith can ignite change across a community.

But this is just the beginning. Building on this momentum, PRADAN—together with the farmers, community-based organizations, and government schemes—has charted a roadmap to deepen and scale the impact of regenerative practices. The vision includes empowering more smallholder farmers through climate-resilient technologies and sustainable farming methods, and expanding the adoption of the Kheyti Net House Model across blocks and villages. A major shift is underway: from input-intensive agriculture to regenerative systems that restore soil health, enhance biodiversity, and secure long-term productivity. Over the next one to five years, the collective aim is to transition 30–50% of farmers in the region to regenerative practices.

Improving access to credit and financial services has emerged as a key enabler in this journey. Through the Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana – National Rural Livelihoods Mission (DAY-NRLM), initiatives such as the formation and strengthening of SHGs, revolving funds, and community investment funds are creating new financial pathways for rural farmers. In parallel, support for both farm and non-farm livelihoods, skill development, market linkages, value chain enhancement, and financial inclusion through credit and insurance is fostering economic stability. The promotion of producer collectives and rural enterprises is central to this effort.

PRADAN plays a facilitative role—mobilizing and building the capacities of grassroots institutions like Producer Groups and SHGs, enabling communities to access entitlements and adopt diversified livelihood models. It supports the establishment of women-led microenterprises, farmer collectives, and local value chains.

Together with local partners, PRADAN aims to foster circular economies rooted in sustainable agri-produce. Plans are underway to form Net House clusters to help farmers achieve economies of scale in both production and marketing. Efforts are also being made to link these groups to relevant government schemes such as Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY) and Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana (PMKSY). The development of Farmer Field Schools, with curricula focused on regenerative and protected farming, will build technical knowledge at the grassroots. Field staff and progressive farmers will be trained as master trainers to extend peer-to-peer learning.

To ensure the longevity of these efforts, greater emphasis will be placed on soil health through the promotion of bio-inputs, composting, cover cropping, and reduced tillage. Practices like multi-tiered cropping systems, intercropping, native seed use, and biodiversity conservation will be promoted across the region. Climate resilience outcomes—such as water-use efficiency, improved productivity, and input cost savings will be carefully tracked to build a strong evidence base.

A special focus will be placed on involving women and youth as entrepreneurs in regenerative agriculture by equipping them to lead activities such as producing and marketing natural inputs, managing nurseries, running decentralized composting units, and providing agri-advisory services within their communities. This will contribute to strengthening inclusive and sustainable livelihoods. A robust monitoring and evaluation framework will be implemented to assess both social and economic outcomes. Success stories will continue to be documented and shared, while tools such as input-output tracking sheets will support better resource planning, reflection, and learning across the system.

*The WEE (Women Economic Empowerment) project carries an ambitious vision: to uplift around 3,00,000 women by enhancing incomes and supporting the growth of women-led enterprises. The goal is to enable 1,00,000 women to earn up to ₹1,00,000 annually, while improving incomes of another 1,50,000 and 50,000 women by 40% and 25% respectively—a step towards not just better livelihoods, but deeper empowerment.

About the Author